Hundreds of millions in payments were made to a firm co-owned by Timur Kulibayev, son-in-law of the resource-rich nation’s longtime ruler.

Western oil giants had a cash bonanza in their sights when they gathered in the small town of Farnborough, southwest of London, in October 2012. They were rushing to exploit one of the world’s richest and deepest oil fields: the 156-square-mile Tengiz reservoir in western Kazakhstan, more than four times the size of Paris and a mile deep, under a desert on the remote north coast of the Caspian Sea.

Time was slipping by on the oil executives’ exclusive 40-year rights to develop the field. They had 21 years left to both extract the oil and build the infrastructure to transport it from Tengiz to the 939-mile Caspian pipeline, where the oil would be exported through Russia and on to world markets.

But the riches lay beneath one of the most politically and environmentally sensitive spots on Earth, where temperatures soar to 130 degrees in summer and sink to 30 below zero in winter. A country settled by nomadic tribes, where guests are still welcomed with camel’s milk, Kazakhstan has a population that includes a large minority of Slavs who migrated south across the 4,500-mile Russian-Kazakh border, and Russia has been a dominant influence there since the tsars. The oil itself is deep under the fragile area known as the Caspian Depression, home to an ecosystem of migratory birds, sturgeon, herring and other rare fauna.

The oil companies listened as representatives of a little-known Kazakh firm called TenizService pitched an idea to build a transportation route and offloading facility to speed removal of the oil by nearly doubling the volume that could be shipped by pipeline to the nearest navigable seaport in Russia. Back in 2009, Chevron and its partners had rejected a similar idea because of safety and environmental risks.

The massive infrastructure project seemed impossible: The Caspian Sea is landlocked and impassable in winter, and the oil reservoir was about 1,000 miles from the nearest usable seaport. Floating docks would need to be built. Asphalt roads would need to be paved. A 43-mile marine channel, able to accommodate vessels from tugs to barges, would need to be dredged.

The approval process was hugely complex, requiring sign-off from no less than 170 officials across 46 Kazakh entities, from local water officials to the Ministry of Transport.

These intimidating obstacles didn’t faze TenizService, which got the contract as the lone bidder. In a 52-slide presentation of photos, maps and schematic drawings, the company proposed a way to win a construction permit in a matter of months, citing its “good relations” with the government.

Despite enormous regulatory hurdles, the project to build the offloading facility — with a price tag of $1.06 billion — moved forward with preliminary work within a month. Chevron, ExxonMobil Corp. and two other partners approved a deal that would ultimately pay TenizService $1.5 billion beyond the original cost of the no-bid contract, for a total of $2.5 billion.

TenizService, the Kazakh firm navigating the hurdles that had stymied Western oil giants for years, had been partly owned until 2010 by the “oil prince”: Timur Kulibayev, the billionaire son-in-law of Kazakhstan’s president at the time. It was in the hands of a business associate when the contract was awarded, and would soon receive a financial lifeline from a bank in which Kulibayev held a large stake.

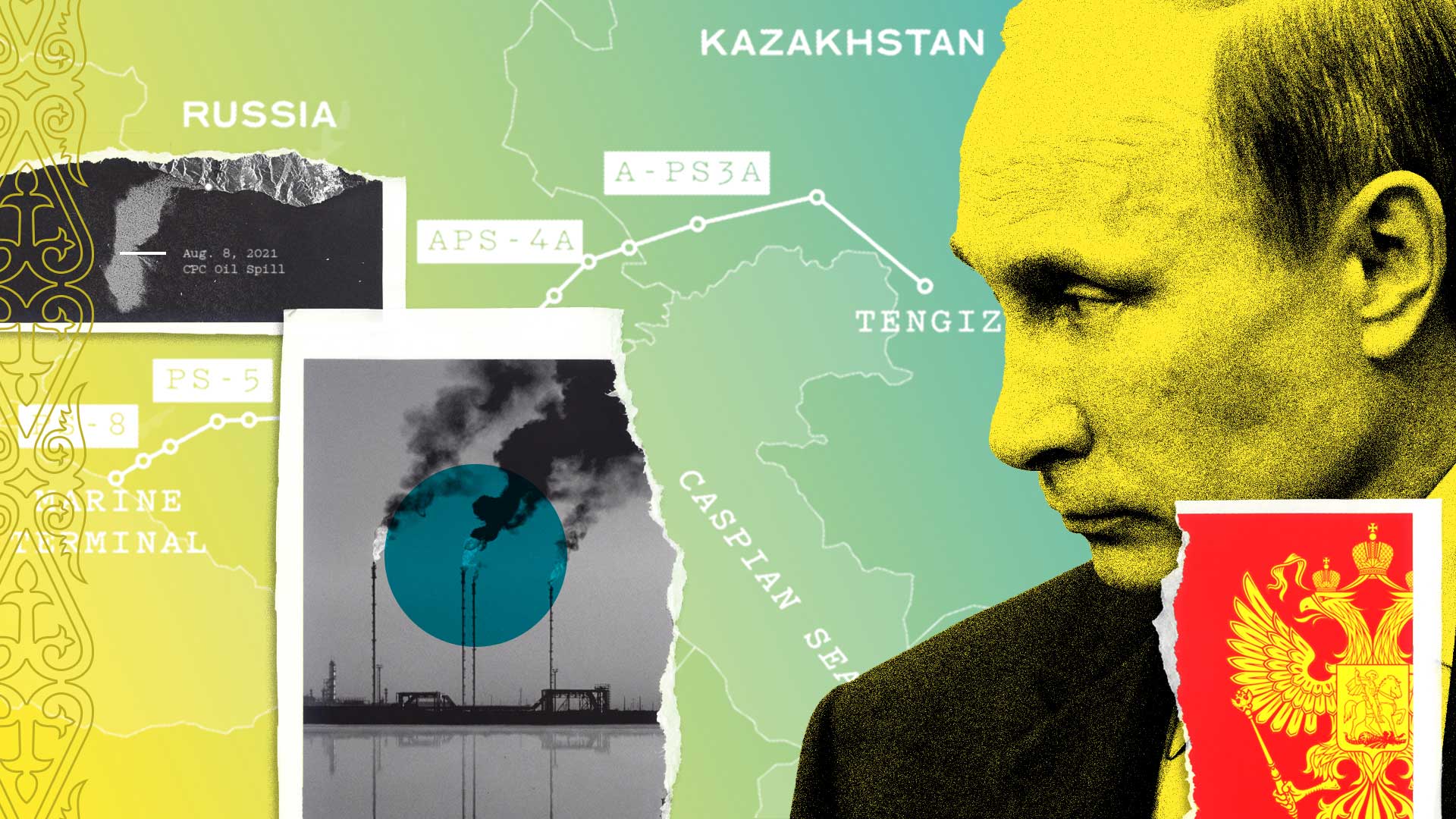

Through his father-in-law Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled petroleum-rich Kazakhstan for nearly 30 years, Kulibayev had ready access to the levers of oil power — power which could help oil companies, Nazarbayev and, ultimately, Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Despite internal warnings that the contracts could be seen as including improper payments to politically influential actors, Chevron, Exxon and three other Western oil giants approved financial dealings with companies linked to Kulibayev. The deals with these firms were part of a broader push by Western oil companies to court politically connected contractors and secure a route to export oil from Kazakhstan, through Russia, to world markets.

Kulibayev’s connections to TenizService are part of Caspian Cabals, an investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 26 media partners into the rise of a critical pipeline in the Caspian Sea region and Kazakh oil fields that feed it. The two-year investigation is based on tens of thousands of pages of confidential emails, company presentations and other oil industry records, audits, court documents and regulatory filings,as well as hundreds of interviews, including with former company employees and insiders. Caspian Cabals shows how Western oil company money has empowered anti-democratic actors in Kazakhstan, bolstered Putin’s regime and enriched regional elites.

Western consumers and oil companies are increasingly dependent on the Caspian region. For decades, U.S. foreign policy and high-powered lobbyists promoted the idea that resource-rich Kazakhstan would help to wean the U.S. from dependence on Middle Eastern oil — while wresting the Central Asian nation from Russia’s influence and expanding democracy in the region.

Caspian Cabals: Key findings

The Caspian Cabals investigation reveals how Western oil companies — including Chevron Corp., ExxonMobil Corp., Shell PLC, and Italy’s Eni S.p.A. — ignored bribery risks and massive cost overruns to secure their stake in a critical Kazakhstan-Russia pipeline, only to be sidelined by the Kremlin. Here are seven key findings from our reporting.Read more

Instead, the Caspian projects emboldened Russia and have come at grave environmental cost to Kazakhstan — generating discontent, anger and disappointment among some of its citizens.

“Fossil fuel development in western Kazakhstan has been devastating to local communities, both in terms of environmental health impacts and destruction of the natural world,” said Kate Watters, executive director of Crude Accountability, an advocacy group specializing in environmental protection of the Caspian Sea. “Children have grown up in the shadow of oil and gas development, and have paid the price with their health, despite claims by corporations and international financial institutions that environmental and social standards are upheld.”

Leila Nazgul Seiitbek, founder of Freedom for Eurasia, placed some of the blame on Kulibayev. Her advocacy group investigated him and asked the U.S. to apply sanctions to punish him for alleged corruption. “Rarely does anyone bear any responsibility in projects where there are interests of the political kleptocratic elite,” she said. “Of course to the extent that Kulibayev has an interest in any project, that plays a role in ensuring impunity. Projects with his participation are generally not available for civilian or law enforcement control.”

Kulibayev declined ICIJ’s requests for an interview.

His U.K. law and communications firm, Schillings, said Kulibayev is an independently wealthy businessman and investor, with his own business interests and a proven commercial track record.

In a 39-page letter to ICIJ’s lawyers, Schillings acknowledged Kulibayev had an indirect, minority stake in TenizService until 2010 but no interest in the company when the giant infrastructure contract was awarded two years later.

“Mr. Kulibayev has never had a monopoly over the oil industry in Kazakhstan,’’ the law firm said. “He was influential due to his prominent roles in the sector, but he by no means controlled it.”

Schillings credited the vast wealth of Kulibayev and his wife Dinara Kulibayeva to their business acumen, not to their unique access to her father, the former president of Kazakhstan, or the highest reaches of government and industry.

“They made their money without any support from the state,” Schillings said. “Mr. Kulibayev has never engaged in bribery or corruption or engaged nominees to act on his behalf in connection with the oil and gas industry in Kazakhstan or otherwise.’’

Today the 58-year-old Kulibayev sits atop an empire of more than 220 companies and trusts in 22 countries, including 10 secrecy havens. He and his wife lead the list of the richest Kazakhs, with a combined fortune of $10 billion, according to Forbes.

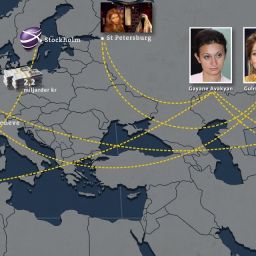

As Caspian Cabals shows, he and his family poured money into mansions across Europe, artwork, a private jet, million-dollar parties and entities registered in multiple countries.The companies registered in the offshore secrecy havens have bought a dizzying array of businesses — farming companies, a medical clinic, real estate outfits, oil and gas service firms, a high-end merchandiser and golf resorts.

In a 2017 Italian corruption case, a businessman named Agostino Bianchi pleaded guilty to bribing three Kazakh officials, including Kulibayev, to get public contracts that netted Bianchi a $7 million profit, according to documents shared by ICIJ partner L’Espresso. A judge in Monza, near Milan, confiscated those illicit proceeds. The businessman got a 16-month sentence with suspended jail time. Kulibayev was not charged. His lawyers said Kulibayev was unaware of the case and he denied having received payments from Bianchi or ever engaging in bribery.

With access to Kazakhstan’s oil fields, Western leaders hoped to reduce their reliance on Middle East oil and forge relationships that could bring democracy to Kazakhstan. As Caspian Cabals shows, however, the Western oil deals helped boost a kleptocracy and Putin’s Russia.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Oa3DMefXug4%3FinitialWidth%3D623%26childId%3Dicij-iframe‑1%26parentTitle%3DOil%2520giants%2520ignored%2520red%2520flags%252C%2520enriched%2520elite%2520for%2520Kazakhstan%2520pipe%2520dream%2520-%2520ICIJ%26parentUrl%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.icij.org%252Finvestigations%252Fcaspian-cabals%252Ftimur-kulibayev-nazarbayev-kazakhstan-oil-riches%252F

The making of an ‘oil prince’

Kulibayev was well-groomed to navigate politics. He was born into power, the son of a Soviet-era Communist Party boss, Askar Kulibayev. His mother, a schoolteacher named Raisa, was trained as a biologist. His father held the top party job in the western Kazakh oil region of Atyrau. In the 1970s, his father’s position meant that as Timur grew up he enjoyed goods and services in short supply — and could summon a car anytime from the Central Committee garage.

After attending an elite high school, Kulibayev studied economics in Moscow at one of the country’s most prestigious universities. He moved in the same social circles as Dinara Nazarbayeva, the middle daughter of the future Kazakh president, who was also studying in Moscow. They married around the time the Kazakh Supreme Soviet elected her father the country’s first president in 1990, a post he would hold for the next 29 years.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought opportunities for both Western oil companies and Kulibayev. Western governments were promoting commerce in newly independent countries, and Kazakhstan’s vast petroleum reserves offered an irresistible option away from their fraught dependence on Middle Eastern oil. Chevron would become the first foreign energy company to enter Kazakhstan.

Kulibayev, 25 in 1991, plunged into a corporate career, honing his finance skills at an investment firm.

Soft-spoken and savvy, the entrepreneur assembled an elaborate and enduring network of friends and business partners. Along with his front-row access to government leverage, this network would eventually help him acquire stakes in the country’s banking and gold businesses, telecom, oil fields, pipeline construction and other industries.

By 1997, Timur and Dinara, now parents to a son, lived in a prestigious apartment building in Almaty, the nation’s most populous city. According to a neighbor, exiled opposition figure and former banker Mukhtar Ablyazov, the four-story building was occupied mostly by state officials who often paid nothing or below market price for their units.. “It was the most expensive and best property in Almaty,” Ablyazov, who later became an enemy of Kulibayev after publicly accusing the president’s son-in-law of accepting bribes, told ICIJ. After he helped found an opposition movement, a Kazakh court convicted Ablyazov in 2017 of embezzlement and related offenses, and a UK court found him guilty of criminal contempt. Ablyazov, who denies the allegations, is wanted in Russia, Kazakhstan and the UK.

Nazarbayev, meanwhile, struck deals with Western oil companies. He signed agreements with Chevron and others for the development of the Caspian pipeline and rights to the giant fields that would feed it. The first contract was for Tengiz, signed in 1993 for a term of 40 years. It established a joint venture company called Tengizchevroil to operate the Tengiz oil field. Chevron became the dominant Western shareholder with its 50% stake. Exxon, with a 25% share, would become the second biggest owner. Nazarbayev planned to bring in investors to construct the pipeline to ship the oil — not only from Tengiz but also from other big Kazakhstan fields called Kashagan and Karachaganak.

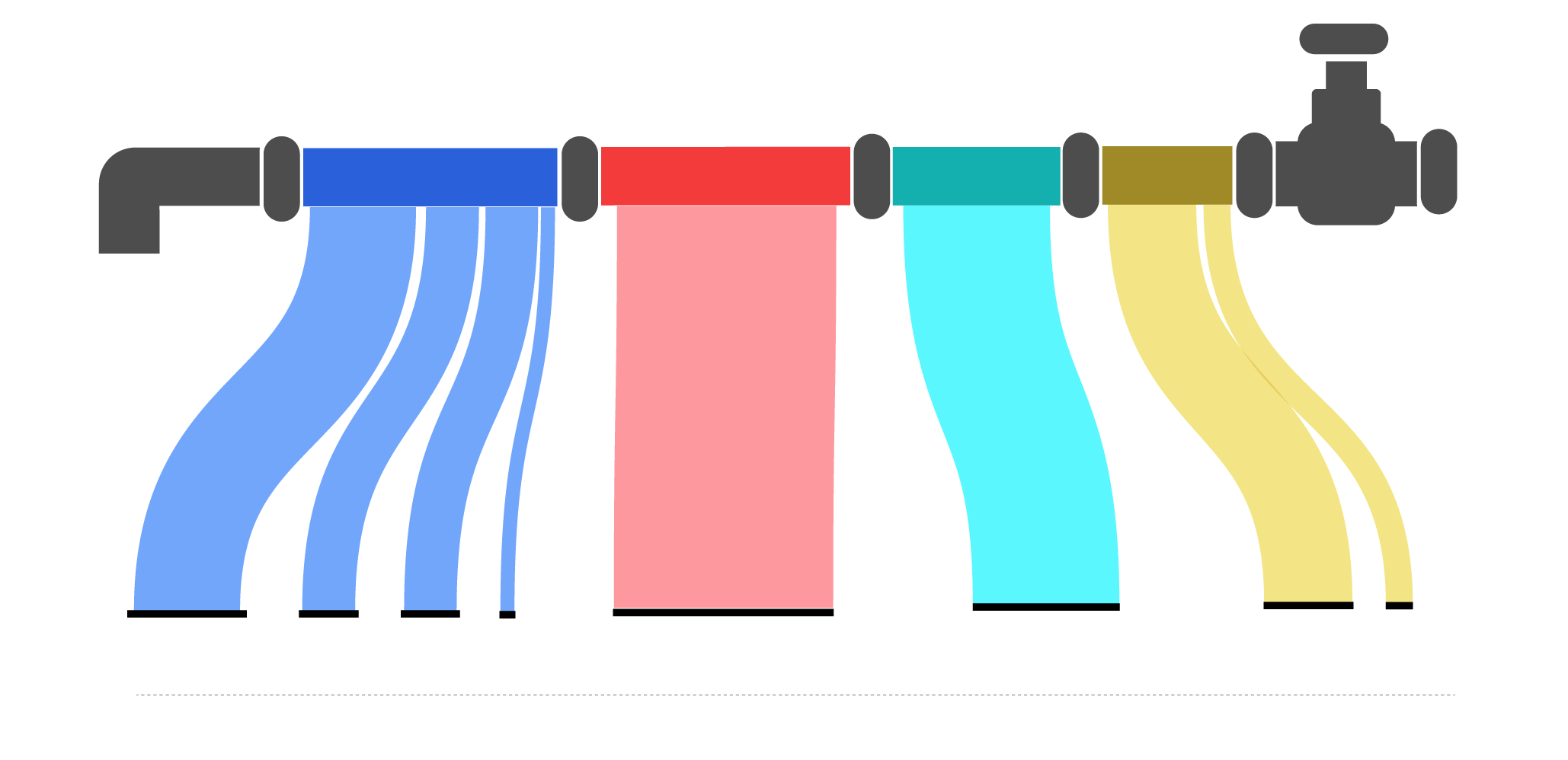

The pipeline’s operating company was named the Caspian Pipeline Consortium. Chevron owned 15% of the consortium, Exxon 7.5%; Shell about 3.7%, Eni 2% and BG Group 2%. The Russian government would eventually become the largest shareholder in the Caspian Pipeline with an initial 24% stake.

Others

companies

CPC

Russian

government

Kazakh

government

Western

companies

Chevron

Shell

Eni

Transneft

KazMunayGas

Lukoil

Rosneft

Exxon

15%

7.5%

7.4%

2%

31%

20.8%

12.5%

3.8%

% of shares held by companies

With these deals, Nazarbayev began to create Kazakhstan’s oil and gas bureaucracy. Meanwhile, his son-in-law joined the government, working under Nurlan Balgimbayev, a one-time Chevron consultant, in different top Kazakh oil posts.

In time, Kulibayev would come to own stakes in privately held firms that once were state-owned, including Halyk Bank, which would eventually become Kazakhstan’s largest bank. His stake in the bank and other former state assets were acquired as he moved in and out of high-ranking government jobs, including vice president of KazakhOil and president of KazTransOil, both state-owned. Then, via presidential decree, he became vice chairman of the new state holding company KazMunayGas, or KMG.

Schillings said in its response to questions from ICIJ that although Kulibayev was part of KMG’s senior management team responsible for overall strategy, he “had no unilateral influence on KMG’s decision-making process.”

The lawyers acknowledged that Kulibayev held government positions and pursued private business interests “in parallel for a period of time.”

“Kazakh law allowed public officials to have outside business interests, so there was nothing improper or unlawful about Mr. Kulibayev’s activities,” Schillings said.

His private empire grew: A small circle of associates and allied businessmen helped manage a web of operating and shell companies that frequently looped back to Kulibayev, Caspian Cabals documents show.

While he never met Kulibayev, attorney Ruslan Tsarni said that during his work in Kazakhstan he acted for representatives of “an organized band of individuals headed by Timur Kulibayev,” which Tsarni called “The Group,” according to a 2010 statement to Ablyazov’s U.K. attorneys in a fraud case brought by BTA Bank against Ablyazov, its former chairman, in the London High Court.

One alleged member of the so-called Group was Arvind Tiku, 54, who was “subordinate and ‘junior partner’ of Kulibayev in some projects,” Tsarni said in a written statement to ICIJ. An Indian-born billionaire, Tiku helped Kulibayev buy Prince Andrews’ Sunninghill country estate in 2007, according to press reports. The house stood empty for years.

In their emailed response, the lawyers for Kulibayev said he purchased Sunninghill Park in a “commercial, arm’s length transaction” and as part of a competitive bidding process.“ Kulibayev did not use Tiku to mask Kulibayev’s involvement in commercial transactions, they said, adding that the two men “have been occasional, transparent business partners.”

In a 2021 video interview with the Swiss newspaper NZZ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung) Tiku said he had prior business interests with Kulibayev but denied he had done anything wrong. “Do I know Kulibayev? No doubt I know him,” Tiku said. “Have I done business with him? Yes. Do I still do business with him? No.”

In a statement to ICIJ, Carter-Ruck, a U.K. law firm representing Tiku, said the businessman had no current business relationship with Kulibayev and never took orders from him. The law firm said Tiku provided Kulibayev’s company with $16 million (£8 million) to acquire the Sunninghill Park property and that the loan and interest were repaid in full in 2010.

Another member of Kulibayev’s circle, Aidan Karibzhanov, founded an investment firm called Visor Investment Solutions. He helped design a process to privatize state assets as a member of Kulibayev’s executive team at KazMunayGas. In a 2021 affidavit filed in federal court in New York, Karibzhanov’s former wife, Makhpal Karibzhanova, said her ex-husband used nominees, or proxies as owners, and pursued oil and gas privatization deals whose profits were channeled through offshore entities.

“Mr. Kulibayev and Mr. Karibzhanov have crossed paths to a limited extent in their professional careers,” Schillings said in its statement. “These connections are transparent.”

Karibzhanov did not respond to multiple requests for comment from ICIJ, but he said in an affidavit filed in his former wife’s New York case that he had “no material financial connection” to the privatization of oil and gas fields in Kazakhstan. He also denied gaining ownership of assets through nominees or straw men.

In a 2013 Facebook post republished in Forbes, Karibzhanov said that while “often Visor is counted as belonging to Timur Kulibayev,” they were partners in only two early projects. He denied Kulibayev was a Visor shareholder.

Schillings said Kulibayev had only a distant, indirect connection to Visor and had no control over the firm or its investment activities. He had been an indirect shareholder in a company that Visor invested in, the law firm said, and a Visor affiliate had purchased a Halyk Bank subsidiary earlier this year.

“Mr. Kulibayev does not own Visor, either directly or indirectly,” Michael McNicholas, general counsel for the Visor Group, wrote in an email response to inquiries by ICIJ. Referring specifically to Visor International DMCC, he said it was owned by six individuals “who have never held, nor currently hold” an equity interest on behalf of Kulibayev. He declined to provide the names of the owners.

In 2003, U.S. prosecutors indicted a consultant to Nazarbayev in a massive bribery case. They accused the American businessman James H. Giffen and his merchant bank, Mercator, of passing $78 million in bribes — and millions of dollars in jewelry, furs, speedboats and snowmobiles, tuition and vacations — from U.S. oil companies to two unnamed, unindicted co-conspirators who have been publicly identified as Nazarbayev and his top lieutenant Balgimbayev.

“Kazakhgate,” as the case became known, centered on transactions between Mercator and Mobil Oil Corp., which became part of Exxon. Neither Exxon nor any other oil company was charged. Kulibayev wasn’t implicated; Giffen pleaded guilty to a tax-related misdemeanor. The judge declined to sentence Giffen to prison after he testified that he acted with support from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and the White House to help advance American interests in the region.

Meanwhile, State Department cables published by WikiLeaks would reveal that Kulibayev was in regular contact with U.S. government officials, providing information on topics ranging from the importance of the Caspian pipeline expansion and potential oil routes through Iran and China to Western companies’ bids for an oil block — a designated area for oil and gas exploration and production — and China’s growing importance in the region. Diplomats gushed over him, praising his “grace of a statesman,” according to a WikiLeaks cable.

In contrast to the glowing views of some diplomats, oil industry insiders complained bitterly about the perils of doing business under the Nazarbayev regime, according to diplomatic cables obtained by WikiLeaks. At a March 2005 focus group of oilmen with the U.S. ambassador in Almaty, one executive criticized “elite corruption” and called out allegations about the president’s son-in-law. “Kulibayev and his ilk prey on foreigners and locals alike,” he said.

Another diplomatic cable, sent to numerous U.S. government agencies, revealed a Kazakh oilman’s more colorful description: “Like a Buddha with a Paris manicure,” he said of Kulibayev, with an “avarice for large bribes.”

On behalf of Kulibayev, Schillings flatly denied the comment, adding that the oilman had a grievance against Kulibayev.

Under a veil

By 2007, Kulibayev had joined the ranks of the ultra-rich, appearing on the Forbes billionaires list for the first time. The Sunninghill Park estate in Berkshire that Arvind Tiku helped Kulibayev obtain was one of six properties totaling around $184 million that Kulibayev’s network of companies purchased in the U.K. that year, ICIJ’s investigation has found. Three of these were in Mayfair — the glamorous London neighborhood dotted with five-star hotels and Michelin-starred restaurants.

Kulibayev purchased two other London properties in an area of Kensington known as “Millionaire’s Row” in 2007 for $54.5 million. Those assets were placed in a Cayman Islands trust.

Around the same time, according to Caspian Cabals documents, Kulibayev and his associates bought real estate through companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions — including the Bahamas and the British Virgin Islands. He and members of his inner circle also created companies in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, Luxembourg and other European countries to buy real estate and manage Kulibayev’s corporate holdings.

During this fast and furious buying spree, government officials in Switzerland and Kazakhstan reportedly investigated possible wrongdoing by Kulibayev and oil industry players — although neither went forward because, Kulibayev’s lawyers said, they could find no evidence against him. Even under scrutiny, Kulibayev’s influence within Kazakhstan grew, helping turn the country into a world energy power.

In 2008, President Nazarbayev appointed Kulibayev to another prominent government post: deputy chairman of the country’s newly created $80 billion national wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, named after a bird in a Kazakh folk story that lays golden eggs and brings luck.

Meanwhile, the government demanded oil companies pay up — in pressure campaigns that took the form of what industry executives described in private discussions with U.S. diplomats as spurious tax charges, demands for discounts on raw materials for local refineries, environmental fines, increased tariffs and reimbursement for what the government said were illegal revenues from overproduction.

Two Chevron executives told the American ambassador to Kazakhstan in 2008 that the company was facing outrageous fee demands. “Chevron views as unacceptable new fees,” reads a leaked State Department cable. Still, the cable made clear, the company would continue to invest in the oil fields because “they affirmed that Tenghiz continues to be extremely productive (and profitable).”

Executives at Chevron-led Tengizchevroil, Exxon and other energy companies hosted events for KazEnergy, the trade group led by Kulibayev that pushed for environmental, tax and other rules in Kazakhstan favorable to the industry. One of the Chevron executives socialized with Kulibayev, too, a Kazakhstan oilman told U.S. diplomats in 2008, according to a WikiLeaks cable, in locations ranging from a golf course in Astana, Kazakhstan’s capital, to a beach in Spain.

No Chevron executive ever provided Kulibayev with “anything of value (bribes, favours or anything else),” his law firm wrote, questioning the accuracy of the Wikileaks cables.

In U.S. government circles, diplomats circulated unconfirmed reports that Kulibayev may have received kickbacks over energy deals involving China – an allegation his lawyers denied. In the words of another cable, he was “behind” traders charging oil companies exorbitant prices to ship oil. His 2011 appointment to the board of the Russian state oil company Gazprom — as the only non-Russian — was seen as a sign of his growing political stature.

Despite the red flags, Chevron and its partners awarded oil contracts to businesses linked to Kulibayev, ICIJ has found. Among the deals: a 2011 contract from the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, whose shareholders include Chevron and Exxon, to build two pumping stations in Kazakhstan.

The winning contractor to build the pumping stations was KazStroyService. Public records show that the private equity firm Kulibayev controls, Singapore-based Steppe Capital, listed KazStroyService among its holdings as early as 2010.

KazStroyService did not respond to repeated requests for comment, nor did the Caspian Pipeline Consortium or Exxon. Chevron did not respond to questions about the KazStroyService contract.

- Recommended reading

BROKEN PROMISES

The lost village: Western oil companies enriched Kazakhstan’s power brokers — and left a community in ruins

Nov 22, 2024

INTERACTIVE

Uncovering Timur Kulibayev’s European property empire

Nov 22, 2024

CASPIAN CABALS

Putin’s pipeline: How the Kremlin outmaneuvered Western oil companies to wrest control of vast flows of Kazakhstan’s crude

Nov 22, 2024

Kulibayev’s lawyers said Kulibayev acquired a 50% stake in KazStroyService in June 2007, but was not involved in the company’s management or contract discussions. And Kulibayev “was never involved in the management of CPC”, the lawyers said, adding that neither Kulibayev nor Steppe Capital played a role in the pumping stations project or CPC’s awarding of the pipeline contract to KazStroyService.

“He has never sought to hide his commercial undertakings or improperly benefit from them,” Schillings said.

In fact, the lawyers said, Kulibayev provided “comprehensive documentation at the request of several KasStroyService investors and other partners” to avoid any potential conflict of interest as he partly owned the company and had roles at state-owned entities.

The bills for the pumping stations job KazStroyService won skyrocketed over time. The projected cost to build the two pumping stations had been $276.5 million, but it ballooned to $486 million, excluding tax, documents show.

As the project’s price tag rose, the Caspian Pipeline Consortium issued 15 change orders. But paperwork for those amendments reviewed by ICIJ provided only perfunctory justification for the increases; many simply cited the need for “additional” work. Some of the welding work was defective and needed to be redone, according to an internal Caspian pipeline publication and an internal contractor’s progress report.

The work dragged on. The pipeline consortium initially said the job would take 2½ years. It was finished 6½ years later, in 2017 — four years behind schedule.

Kulibayev’s lawyers blamed the delays on numerous design changes by CPC and other difficulties not the fault of KazStroyService. Changes and cost overruns are common on such megaprojects, they said, adding that neither Kulibayev nor Steppe Capital was involved in any discussions about welding work, change orders, or any other part of the contract discussions.

While both the project’s timeline and cost swelled, Kulibayev and his network continued to bankroll their lavish lifestyles. Kulibayev spent nearly $1.6 million on just some of the expenses for summer holidays and his wife Dinara’s birthday celebration at the couple’s home in Lloret de Mar, Spain, called Can Juncadella. A Kulibayev-owned jewelry company, Viled, hosted an exhibition in Barcelona attended by wealthy vacationers and family friends of the Kulibayevs. According to documents reviewed by ICIJ that list the jewelry alongside the names of clients interested in buying them, Kulibayev’s wife expressed interest in buying more than $6.7 million worth of jewelry, including heart-shaped diamond earrings and a pink sapphire pendant surrounded by round and pear-shaped diamonds.

Meanwhile, Nazarbayev was rebuilding Astana as an entirely new capital city, complete with a golden imprint of his hand at the top of the 318-foot tall Bayterek (“tree of life”) Tower — a testament to a despot tightening his grip on power. He severely restricted press freedom, cracked down on political opponents and signed an amendment to the constitution giving him the right to run for president in perpetuity.

The increasing wealth of elites created a sharp contrast to the lives of the working class, which struggled with low wages, poor benefits and dangerous working conditions. Efforts to form trade unions failed. Activists and journalists were attacked or jailed.

Saulesh Yessenova, an anthropologist at the University of Calgary in Canada who investigated working conditions at the Tengiz field, told ICIJ that the 1993 agreement between Chevron and the government of Kazakhstan granting the American company rights to develop the huge field was one cause of worker discontent. The contract granted the government bonuses, taxes, royalties and economic development projects, but the terms were secret.

According to Yessenova’s research, the government would receive 80% of the profits and a $450 million “signature” bonus. But $420 million would be withheld until after the Caspian pipeline was built. Perhaps more important, the government was forbidden from revealing information about the contract. The secrecy of the provisions “seriously obstruct[ed] democratic processes” in Kazakhstan, Yessenova said.

Domestic unrest led to mass protests. In December 2011, government security forces in the oil town of Zhanaozen sprayed bullets on unarmed residents and striking oil workers protesting poor wages and working conditions, killing 17.

At a public forum two months earlier, attended by oilmen, politicians and others, Kulibayev blamed years of unrest on an overpopulation of migrant workers. “Zhanaozen should have been closed for migrants long ago because the town’s social infrastructure is not capable of accommodating so many people,” he said.

Complaining that subordinates had kept him in the dark, President Nazarbayev fired his son-in-law as head of the sovereign wealth fund for allegedly bungling the oil worker strike. Afterward, Kulibayev kept a low public profile. Behind the scenes he continued to act as a gatekeeper for the oil industry through his leadership of the trade group KazEnergy, made up of every major oil company in the country. In diplomatic circles Kulibayev had been dubbed “the Hydrocarbon Richelieu,” a reference to the famed 17th-century French cardinal and power behind the monarchy.

As members of the Chevron-led Tengiz consortium searched for a path to maximize their Kazakhstan investment, they would soon look to a company familiar to Kulibayev: TenizService.

‘All roads lead to TK’

With the expansion of the Caspian pipeline underway, Chevron and its partners sought to dramatically increase the amount of oil they could feed the pipeline by kickstarting production at the Tengiz field — leading to the October 2012 meeting outside London. TenizService representatives presented their plan to speed up the permitting process by relying on what they called the firm’s “good relations” with the government. “TS experience will guarantee getting approval for Project Execution of state authorities in time,” the presentation said.

To get the oil out, Chevron and its partners would undertake a costly project littered with questionable payments, potential conflicts of interest and offshore companies that obscured the owners’ identities, according to Caspian Cabals documents.

One of those opaque companies was TenizService. Partly privatized by the government in 2003 — with the help of Kulibayev’s one-time business associate and former KazMunayGas colleague, Aidan Karibzhanov, whose private equity firm Visor partly owned TenizService — TenizService developed rock-loading, waste management, fire response and marine fueling facilities and provided logistics services to Western companies.

Karibzhanov did not respond to multiple requests for comments. Schillings said Kulibayev played no role in the partial privatization of TenizService.

An organizational chart included as an exhibit in the Ablyazov civil fraud case in London puts “TK” atop a structure of companies, including one business the chart says is “held in name of Visor Investments.”

“It is well known in the Kazakhstan business community that Visor was and is owned and controlled by Kulibayev through front men, including Karibzhanov,” according to attorney and former insider Ruslan Tsarni’s 2010 statement in the London case.

Asked about the statement, Tsarni told ICIJ that he did not know Karibzhanov, never worked for Visor and had no first hand knowledge but “it was broadly known then that Karibzhanov is ‘Kulibayev ‘s guy.’”

Schillings disputed Tsarni’s accounts, claiming he cannot be considered credible or an independent witness because of his connections with the case of Ablyazov, the convicted banker, whom the law firm claimed was spreading false information and was part of a “sustained campaign” against Kulibayev.

The London court rejected Ablyazov’s case and awarded a $4.9 billion judgment against him, Schillings said. The court found Ablyazov guilty of contempt of court for concealing illicit assets and issued a 22-month prison sentence. France granted Ablyazov political asylum, then later revoked it but has yet to enforce the revocation.

Kulibayev “has never owned, managed or controlled any Visor funds,” Schillings said, nor did he have any direct or indirect interest or control in any other Visor entity.

A confidential suppliers’ questionnaire prepared by Tengizchevroil and obtained by ICIJ’s media partner Der Spiegel describes TenizService as 49% owned by KazMunayGas, the Kazakh national oil company, and majority owned by a company called Waterford International Holdings Ltd. Waterford, in turn, was owned by offshore companies, including one with Visor shareholders.

Want to know when we publish?

Help us change the world. Get our stories by email.Sign up

Schillings said that it appeared Karibzhanov owned shares in TenizService through Waterford.

Oil industry executives tried to untangle the convoluted ownership of the companies operating within the large oil fields. “It’s tough to say who owns what,” said Dan Houser, then a vice president of the U.S. oil services firm J. Ray McDermott, according to a 2010 State Department cable.

Behind the ownership structures, he said, “all roads lead to TK” — Kulibayev – a comment Kulibayev lawyers called “pure hyperbole.”

Atradius DSB, the credit insurer of the Dutch state, which covered the project for dredging contractor Van Oord, asked TenizService to disclose its beneficial owners and didn’t get an answer, according to sources and documents obtained by ICIJ’s Dutch media partner NRC. TenizService, according to Atradius, is nothing more than a “vehicle.”

Internal documents, including emails from oil company compliance and audit managers, obtained by Der Spiegel, reveal concerns about the project — such as TenizService’s relatively small size, environmental issues, questionable payments, questionable vetting and “potential indirect connection” to an unnamed government official.

Less than two weeks after TenizService’s pitch to build the offloading facility, Jon Clements, a Tengizchevroil manager, urged quick approval for TenizService to start survey work before the Caspian Sea froze. “We are going to lose ability to have [TenizService] perform survey work before freeze up unless we release them ASAP,” he wrote.

Three days later, Tengizchevroil project director Paul Benoit confirmed that “due to urgent project needs,” TenizService could move forward with the deal — even though neither a contract nor anti-corruption review had been completed.

Compliance officers warned the TenizService deal raised concerns that the Kazakh firm might be engaged in questionable payments to win the permits. Exxon originally opposed the project over such concerns, former Chevron lawyer Mark Egan said in a leaked memo.

Chevron manager Joseph “Al” Ducote wrote just nine days before the deal went through: “The compliance and due diligence issues around this TenizService contract for Prorva port work is very bright on a lot of radars.”

Asked if Kulibayev’s government connections helped fast-track the project, Kulibayev’s lawyers said he was not involved in Tengizchevroil’s management or board. Nor was he involved in the awarding of the TenizService contract, they said.

The Tengizchevroil partners soon realized that TenizService couldn’t finance the project without significant help, according to an email exchange between contract officers, obtained as part of Caspian Cabals. So TenizService turned to Halyk — the bank majority owned by Kulibayev — for a $100 million line of credit.

Kulibayev’s lawyers said that as of December 2018, TenizService had an outstanding loan from Halyk Bank, but they were unaware of any line of credit.

By 2014, Tengizchevroil had revised the contract and taken on much of TenizService’s work. It assigned its own people to many of the jobs and limited the Kazakh firm’s role mostly to licensing, authorizations and permitting — and paid TenizService nearly $800 million extra.

Three years into the project, Tengizchevroil internal audit supervisor Katerina Vardashko raised questions about certain invoices and fees, including some that were described in Russian as commission fees for obtaining permits from local authorities. “We need to get any documentation that explains” the fees, she wrote, adding that the Russian description seemed to make them “even more questionable.”

In August 2016, an internal Tengizchevroil email obtained by Der Spiegel with the sender’s identity redacted arrived in the inbox of project managers: “Please, be informed that a lot of unclear things are happening regarding the Marine Channel project,” it said. ”Amounts are very highly raised multiple times. Prices are very high … they set just ‘crazy’ amounts of money. Please, take it under advisement.”

And the benefits kept coming. At the end of the project, Tengizchevroil handed over the entire $2.5 billion shipping facility to TenizService.

Haymish Paulse, a spokesman for Tengizchevroil, said the consortium is reviewing ICIJ’s findings but declined to answer questions about the contracts or whether Kulibayev played any role.

“[Tengizchevroil] is a law-abiding company and implements stringent policies and procedures regarding compliance and business ethics,” Paulse said.

TenizService did not respond to questions about its beneficial owners, connections to Kulibayev or Halyk Bank, project permits or massive project cost increases. Exxon, KMG and Lukoil also did not respond, nor did a spokesman for the Kazakh Energy Ministry.

In a written statement, Chevron senior media adviser Sally Jones said the company has robust compliance procedures. “Chevron is committed to ethical business practices, operating responsibly, conducting its business with integrity and in accordance with the laws and regulations” where it operates, she said.

Egan, the former Chevron lawyer assigned to Tengizchevroil and the TenizService contract, told ICIJ in a written statement: “I can state categorically that I am aware of no illegal or unethical conduct or wrongdoing whatsoever by Chevron or TCO in connection with TCO’s contract with TenizService.”

Cashing in

After nearly 30 years as president of Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev abruptly resigned in March 2019. His handpicked successor, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, vowed to clamp down on the theft of state assets, face down oligarchs and redistribute the nation’s wealth more evenly.

Local media reported that the new government moved to lift the lid on Kulibayev’s assets and demanded a company controlled by Kulibayev return fuel depots that courts ruled his company had illegally privatized in 2001, along with several land plots in sought-after parts of Almaty. In a separate case, prosecutors demanded that a company belonging to his 87-year-old father, the onetime Communist Party boss who had served as minister of construction, housing and development, return a $66 million oil terminal on about 330 acres.

Lawyers for the elder Kulibayev said he was not personally implicated. His son wasn’t accused of any wrongdoing and has not had to return anything, Schillings said.

The government of Kazakhstan filed arbitration claims for more than $150 billion against four oil companies — Eni S.p.A., Shell PLC, Exxon and TotalEnergies SE — for allegedly failing to deliver on billions of dollars in promised revenue at the Kashagan field. According to media reports, the country alleged corruption tainted some contracts.

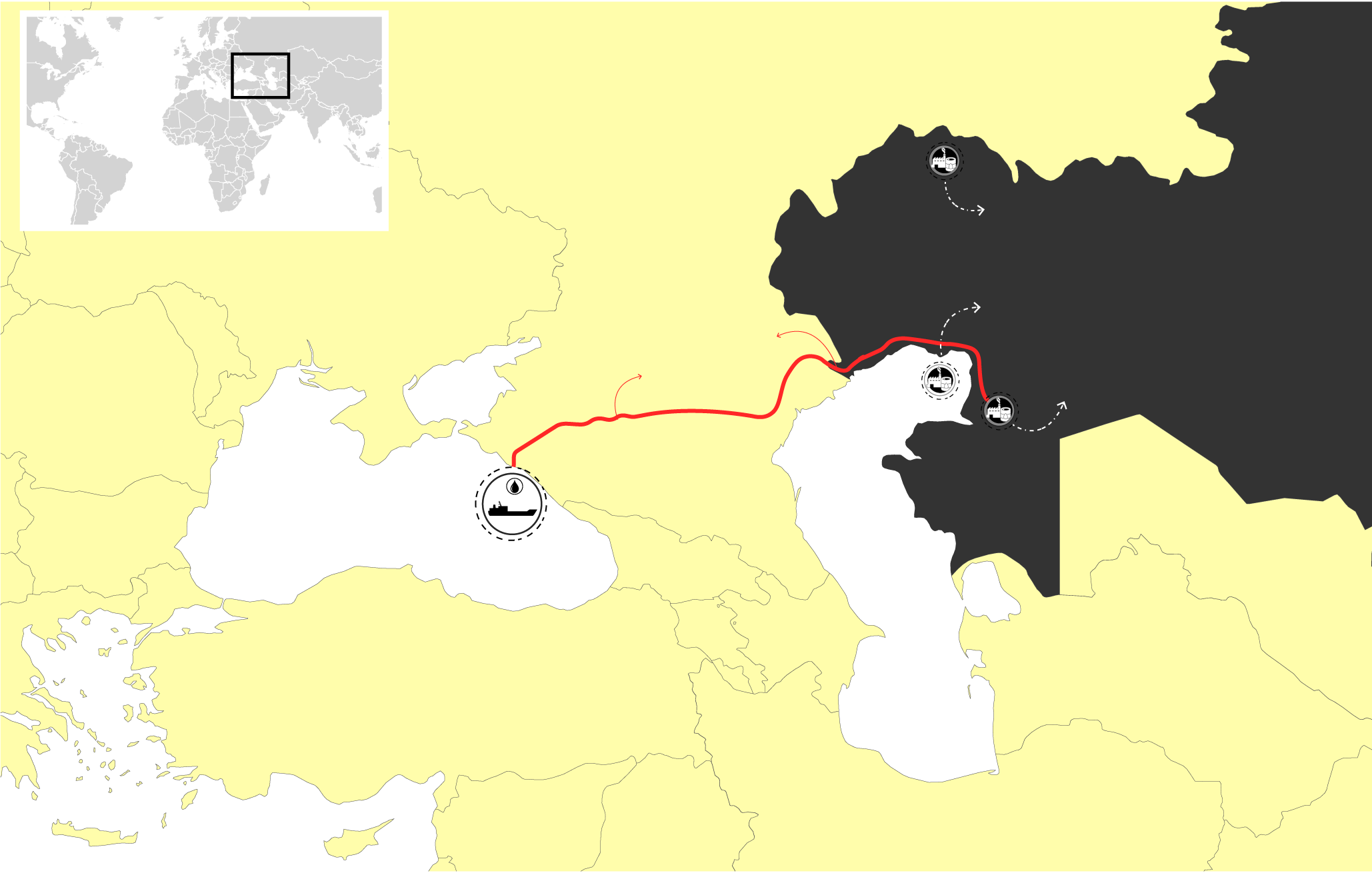

Karachaganak

Ukraine

Russia

Kazakhstan

Kashagan

CPC pipeline

Tengiz

Port of

Novorossiysk

Romania

CPC terminal

Black Sea

Uzbekistan

Bulgaria

Caspian Sea

Georgia

Azerbaijan

Armenia

Turkmenistan

Turkey

Mediterranean Sea

Syria

Iraq

Iran

Exxon did not comment on the arbitration claims, nor did Shell. TotalEnergies referred questions about the arbitration claims to Kashagan’s operating company, which did not comment other than to say it operates responsibly and complies with the law. Eni said it is reviewing the arbitration claims but they “appear neither credible nor substantiated.”

None of these repercussions has affected Kulibayev’s immense wealth. His net worth — not including his wife’s fortune — has reached $5 billion, according to Forbes’ latest annual billionaires ranking.

He owns properties in the Czech Republic and in the German spa town of Baden-Baden; a medical clinic for “regenerative medicine” in Barcelona with multiple parking spaces; and a sprawling estate along Spain’s Mediterranean coast, an ICIJ review of corporate and land records found. Kulibayev’s 100-foot yacht, Sonny II, which he bought in 2014 for about $14 million, is moored in Barcelona.

Emails, invoices and other documents analyzed by ICIJ show that Kulibayev’s companies’ assets over the years have also included a $74.4 million Airbus A320 and a $55 million Gulfstream G650. Representatives for Kulibayev confirmed to ICIJ that his company “owns one private jet and has another on order”and that “once that jet is ready, he may sell the current one”.

In March 2020, APH Property Trust Ltd., where Kulibayev is listed as a “settlor” (the party who transfers assets into the trust), held residential property in the United Kingdom, according to documents that came from a trove of 100,000 leaked files from Genesis Trust, a Cayman Islands-based financial services provider.

The documents show that Kulibayev’s lavishly funded trust listed Gaukhar Ashkenazi, Kulibayev’s former partner, as its protector, or a kind of overseer.

A second trust, called Continuum Trust Ltd 2, held securities, private equity investments and artwork valued at more than $99 million in 2020, including a clay copy of Auguste Rodin’s “The Kiss.”

ICIJ couldn’t verify if the trusts are still active, as information about Cayman Islands-based trusts is not made public.

Farrer & Co, a London-based law firm representing Ashkenazi, said she is an independently successful businesswoman. The law firm asserted that the assets held by the APH trust were valued at about $49.6 million in March 2020. The lawyers acknowledged that the APH Trust listed a pair of properties in London’s Kensington area, purchased in 2007.

By contrast with that immense wealth, many Kazakh citizens have continued to struggle with economic hardship. In January 2022, a sharp spike in fuel prices in Kazakhstan sparked protests and riots as citizens rebelled against corruption, poverty and inequality. At least 238 people died in the violence.

That same month, Kulibayev’s charitable foundation donated $4.2 million to health, education and other programs, according to his lawyers. That was part of $103 million they said his Halyk Charitable Foundation contributed to humanitarian causes since 2016, including $65 million to flood victims in Kazakhstan’s Atyrau region, where the Tengiz field is located.

His father-in-law, Nazarbayev, has disappeared from politics. But his name can be found across Kazakhstan: the airport, a university and a street in Almaty are named after him.

Meanwhile, Chevron has raised the cost of its massive Tengiz infrastructure project to $48.5 billion — up from $36.8 billion in 2016, an increase of 32% — fueling concern among investors.

The company says the partnership has “become a catalyst for boosting economies, creating jobs, supporting businesses, building communities, empowering people and advancing critical sustainable development goals.”

In the last 30 years, Chevron, Exxon and the other Tengizchevroil partners have paid more than $190 billion to Kazakh entities — for employees’ salaries, goods and services, and tariffs and fees paid to state-owned companies — according to a fact sheet published by the consortium last year. This also included more than $100 billion to the government over the past decade. That’s an average of $10.8 billion a year, making Tengizchevroil one of Kazakhstan’s largest taxpayers.

Reformist lawmakers say Kazakhstan suffers from the “oil curse” — which produces a mountain of cash but no democracy and little to lift the poor — since it signed the first contracts with Western oil companies. They have demanded audits, investigations and disclosure of all the contracts but the oil companies and the government of Kazakhstan have refused to make the contracts public.

“Nazarbayev’s circle, his relatives, sons-in-law, daughters became rich thanks to the fact that they have such a patron-father. There are a lot of such capable kids who could become billionaires if they had a father like Nazarbayev,” Yermurat Bapi, a member of Kazakhstan’s parliament and former newspaper owner, said in an interview with an ICIJ reporter in an Astana coffeehouse. “In our country, only Nazarbayev’s circle is engaged in oil and gas — others are not allowed,” added Bapi, who has a history of criticizing the government on corruption.

Meanwhile, Dutch media reported that prosecutors in the Netherlands are looking into whether Dutch dredging company Van Oord had an improper financial relationship via an intermediary with the father of a son-in-law of Nazarbayev. They did not name the son-in-law.

Schillings said the elder Kulibayev has not been notified or questioned about that investigation. “As far as he is aware, he is unconnected to it,’ Schillings said.

Do you have a story about corruption, fraud, or abuse of power?

ICIJ accepts information about wrongdoing by corporate, government or public services around the world. We do our utmost to guarantee the confidentiality of our sources.

A coalition of advocacy groups has tried unsuccessfully to get the Biden administration to sanction Kulibayev and others in the Central Asian country.

They say human rights abuses go hand in hand with corruption in a country where “the ruling elite uses its power to appropriate the wealth of their nation by embezzling government funds and controlling money-making enterprises,” a confidential report submitted in 2021 to the U.S. State and Treasury departments says, calling for Kulibayev to be sanctioned for alleged corruption. “The line between public and private in Kazakhstan is thus virtually non-existent,’’says this report, submitted by Freedom for Eurasia and Kazakh NGO Liberty. “A small group of families dominate the business sphere, families who are at the same time involved in the country’s political system.”

During a sanctions debate in the U.K. House of Commons on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, U.K. lawmaker Margaret Hodge called for investigations into Kulibayev and other Kazakh oligarchs with an eye toward imposing sanctions. “Evidence suggests that Kulibayev abused his position to accrue vast wealth,” she said. Kulibayev left the Gazprom board in early 2022. His representatives say he resigned voluntarily shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The State Department did not comment on the advocacy groups’ report and the Treasury Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment. An officer at the U.K.’s National Crime Agency told ICIJ in May they did not investigate. The NCA spokesman declined to comment in November.

[The U.S.] has pressured Kazakhstan not to take any actions against the oil companies’ massive failures … It’s a comfortable arrangement for the oil companies, but it has cost the citizens of Kazakhstan dearly.— businessman James H. Giffen

In Washington, another call for a review of corruption in Kazakhstan came from U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, ranking Democrat on the House Homeland Security Committee. Thompson cited Kulibayev in House floor remarks about why the U.S. needs to upgrade its anti-corruption efforts to target kleptocrats. “Fighting corruption is an imperative for the United States,” Thompson said in 2021, urging his colleagues to pass a bill to beef up enforcement against kleptocracies and graft. “As a beacon of liberty and the rule of law, it is our duty.”

The bill, which would have created a fund from companies found liable under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, went nowhere.

In an interview with Columbia University’s Harriman Institute three years before his death in 2022, Giffen, the middleman who had helped negotiate some of the original deals with Western oil companies, said that Kazakhgate had as much to do with U.S. politics as with corruption.

“The U.S. government, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, has pressured Kazakhstan not to take any actions against the oil companies’ massive failures on Kazakhstan’s oil projects,” Giffen said. “It’s a comfortable arrangement for the oil companies, but it has cost the citizens of Kazakhstan dearly.”

Contributors: Will Dahlgreen, James Oliver (BBC); Marcel Rosenbach (Der Spiegel); Carina Huppertz, Hannes Munzinger (Der Spiegel/Standard/Paper Trail Media); Pelin Unker (DW Turkey); Ritu Sarin, Sukalp Sharma (Indian Express); Paolo Biondani, Leo Sisti (L’Espresso); Carola Houtekamer, Karlijn Kuijpers (NRC); Anuška Delić (Oštro); Roman Badanin, Mikhail Rubin (Proekt); Stefan Melichar (Profil); Manas Qaiyrtaiuly, Reid Standish (RFE/RL); Luc Caregari (Reporter.lu); Sylvain Besson (Tamedia); Vyacheslav Abramov (Vlast.kz/OCCRP); Olga Loginova, Paolo Sorbello (Vlast.kz); Naubet Bisenov, Nicole Sadek, Thomas Rowley, Peter Stone (ICIJ)

Correction Nov. 25, 2024: An earlier version of this story erroneously stated that Timur Kulibayev was listed in a 2012 Steppe Capital annual report as the “sole shareholder” of KazStroyService. Kulibayev was listed in the document as the “sole shareholder” of Steppe Capital. Kulibayev acquired a 50% stake in KazStroyService in 2007, according to his lawyers.

Update Dec. 9, 2024: After further correspondence from Timur Kulibayev’s representatives, this story was updated. The update includes that Kulibayev left the Gazprom board in early 2022. His representatives say he resigned shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The update also includes Kulibayev’s denials of receiving payments from Agostino Bianchi or ever engaging in bribery.

Source: ICIJ

By Sydney P. Freedberg, Agustin Armendariz, Tanya Kozyreva, Matei Rosca and Marcos Garcia Rey

Image: Ben King / ICIJ

November 22, 2024