A new report details, in part, how Kazakhstan’s president has helped define the new authoritarian normal.

From ossifying dictatorships in Russia and Venezuela to proto-autocratic leaders in Hungary and the Philippines, it’s clear that the 2010s are rapidly being defined as an era of democratic retrenchment. Instead of relying solely on brute repression, however, elites within rising authoritarian regimes have found another tool that preceding autocracies could have only dreamed of: a trans-national financial network that the remaining democracies, including the United States and United Kingdom, have been only too willing to provide to ruling post-Soviet, Gulf, and Chinese oligarchs.

As Ben Judah ably displays in a new report from the Hudson Institute, it is these networks — these means of offshorization, shell corporations, and legal loopholes — that have allowed the corrupted elites in remaining and prospective autocracies to park their ill-gotten gains abroad, from Manhattan lofts to anonymous companies in Panama and the British Virgin Islands. Indeed, as Judah notes, we have entered a “golden age of money laundering,” with as much as 5 percent of worldwide GDP standing as laundered money. “It has never been simpler or safer to be a kleptocrat,” Judah adds, pointing to an estimate from investigative economist James Henry that upwards of $32 trillion is being held offshore. “Globalization’s deep, structural motors are in fact enabling authoritarians.”

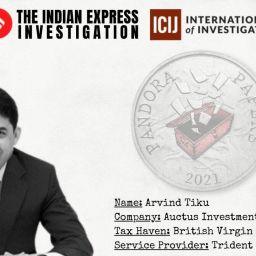

As Judah details, few leaders illustrate the rise of the new authoritarians, especially as it pertains to warping Western actors to his bidding, better than Kazakhstani President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Nazarbayev’s corruption isn’t necessarily a surprise; a decade ago, U.S. officials were describing Nazarbayev as the most “notoriously corrupt” leader “in the free world.” In the years since — with Nazarbayev taking 98 percent in the last presidential election, and with Kazakhstan now facing its first recession in nearly two decades — little has changed.

If anything, Nazarbayev has reified a model that other autocrats have been eager to imitate. “Nazarbayev is the new normal; contemporary authoritarians are mostly kleptocrats,” Judah writes. “This means corruption is not a feature of their regimes, but rather the invariable nature of their rule.”

Not only has Nazarbayev parked his funds in London’s property market, “but his wealth and that of his clique has been funneled out of the country by exploiting offshore networks. In the 21st century Nazarbayev is not the exception, but the norm; he is paradigmatic of the new authoritarians for whom there is no containment.”

But it’s not simply that Nazarbayev’s regime has taken full advantage of the shadow-financing proffered by the West. If anything, Nazarbayev has bought in fully to the “wealth defense industry” pushed by Western actors, including bankers and accountants, lobbyists and public relations experts. To wit, Tony Blair’s role as an official adviser to Nazarbayev, which has only now begun wrapping up, allowed Astana to ignore anti-corruption advice from the West, resting fully upon the hypocrisy attendant in Blair’s presence in Kazakhstan. This comes in addition to the PR machine Kazakhstan has unleashed on both sides of the Atlantic, with Western firms eager to take Astana’s excess hydrocarbon funds to whitewash the country’s Soviet-era leadership.

To be sure, while Nazarbayev stands as an exemplar of the expansive dictatorships taking advantage of Western financial and lobbying networks, Kazakhstan is but one of numerous autocracies detailed in the recent report. China, for instance, has seen its relationship with the West “warped by the dynamics of this shadow system,” Judah writes. “China is bleeding billions in illegally transferred funds… Today some $1 trillion dollars leaves China annually.” Meanwhile, the “most extreme and successful case of kleptocratic takeover to date was undertaken by Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev, the head of a dictatorship that has ruled the country since 2003.” And according to one researcher — in one of the most remarkable stats throughout the entire report — more than half of Russia’s wealth remains squirreled offshore.

Western systems of shell corporations and offshorization not only weaken the West’s soft power, but further entrench the nascent dictatorships mushrooming in place of failed efforts of democratization. While the United States is finally playing a bit of catch-up, elites throughout post-Soviet autocracies have proven over-eager to stash their funds abroad, instead of reinvesting their largesse in domestic industries.

The systems, and the abuse therein, are clear. The time has come, as Judah writes, for the West “to reevaluate authoritarians like Nazarbayev.”