The accused is a star of one of Kazakhstan’s most-vaunted success stories: the Bolashak scholars program.

Sometimes a corruption case is about more than just the corruption. The downfall of Kuandyk Bishimbayev is a story about how Kazakhstan continues to struggle to uproot graft and how the scourge has been handed on seamlessly to a generation in which the elite had placed great hopes of a more transparent future.

Bishimbayev was detained by anti-corruption agents in January 2017, almost two weeks after being summarily fired from his job as National Economy Minister. Investigators announced they suspected him of taking bribes during his time at the helm of the state-run Baiterek holding company, an entity tasked with ensuring implementation of the government’s economic development goals.

In April, while awaiting a trial that started in November 2017 and is now reaching its conclusion, Bishimbayev turned 37 years old.

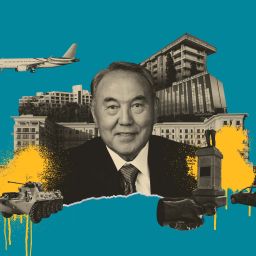

Bishimbayev is one of the best-known graduates of one of Kazakhstan’s most-vaunted success stories: the Bolashak scholars program. Named after the Kazakh word meaning “future,” Bolashak was created by President Nursultan Nazarbayev in 1993 with the express goal of modernizing the country by having Kazakhstan’s most promising young people study at top-class universities around the world. In 2005, Nazarbayev decreed that it should become mandatory for all deputy ministers to have studied abroad.

Bolashak could have been tailor-made for Bishimbayev, who completed his studies in international economic relations at the Kazakh State Management Academy (now called Narxoz University) by the time he was 19 years old. He then squeezed in an MBA at George Washington University in the middle of obtaining a law degree at Taraz State University. In March 2015, Bishimbayev became chairman of a Bolashak old boys association — a sure sign of the esteem in which he was held by that cohort

He got a job in the presidential administration in 2008 and was named an adviser to Nazarbayev himself in 2009. At later junctures, he occupied posts as a deputy trade minister and vice chairman of the Samruk-Kazyna sovereign wealth fund.

The scale of the promise has made the disgrace all the more eye-catching.

“The Bishimbayev affair has drawn so much attention not because of how high-ranking he was. After all, after two high-profile trials of Kazakhstani prime ministers, it is hard to shock the general public,” Sultanbek Sultangaliyev, head of the Rezonans think tank, told Eurasianet. “This is the first time that such a prominent and distinctive member of that new generation of state managers […] has been tried on corruption charges.”

While the judge at the Astana Specialized Inter-District Criminal Court has yet to pass a verdict on Bishimbayev and his 22 fellow defendants, it is almost unknown for trials to reach this stage in Kazakhstan without a conviction. Prosecutors are asking for a 12-year jail sentence. Bishimbayev has adamantly denied the accusations against him, although he did in an impassioned address to court apologize to Nazarbayev for “hiring people whom I knew and who let me down.”

Sultangaliyev said that the confidence afforded to the potential of management class-shaping initiatives like Bolashak was always misplaced.

“These illusions are not to do with the professionalism and creativity , but with the idea that young blood might be immune to corrupt forms of personal enrichment,” he said.

Placing this trial in a broader historical context, political analyst Talgat Ismagambetov argued that Kazakhstan continues to be blighted by a culture of impunity.

“Even when officials engaged in illegality are caught in the act, they just move on from those posts — and no attention is drawn to the fact, so as not to ruin the department’s reputation,” Ismagambetov told Eurasianet. “With this kind of impunity, corruption could not be uprooted.”

On paper, however, Kazakhstan appears strongly committed to finally tackling the issue. In his annual address to the people in January, President Nazarbayev reprised an oft-rehearsed theme, stating that upholding “the rule of law and the fight against corruption remain priority areas of state policy.”

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2017, which was published this week, noted a slight improvement in Kazakhstan’s performance over the past year. The news was greeted with subdued enthusiasm by the Civil Service Affairs and Anticorruption Agency.

“Our country rose nine positions. In 2016, Kazakhstan was in 131st place. […] In 2017, Kazakhstan is in 112nd place, alongside countries like Azerbaijan, Moldova, Liberia, Mali and Nepal,” the agency said in a statement on Facebook, adding that the country is outperforming post-Soviet peers like Ukraine, Russia and Kyrgyzstan.

Madina Nurgaliyeva, deputy director at the state-affiliated Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies, insisted that the government is indeed in a tireless battle against corruption.

“Lately, there has been a lot of media attention on high-profile corruption cases, and there have been trials involving very famous and high-ranking figures. And there are also many mid-level corruption cases ‚” Nurgaliyeva said. “Even though the level of corruption in Kazakhstan is still quite high, we are seeing some positive movement.”

A catalog of cases has indeed piled up over the years, although the pattern in which those scalps have been taken suggests a scattershot, rather than systematic, approach. Among the most notable cases was that of Talgat Yermegiyayev, former chairman of the Expo-2017 fair, who was sentenced to 14 years in jail in 2016 for embezzling around $25 million. In 2015, ex-Prime Minister Serik Akhmetov got 10 years in prison for misappropriating $6.8 million. That penalty was reduced twice after appeal hearings — one of which featured a groveling apology to Nazarbayev from Akhmetov — so that in September the sentence was commuted to “limited freedom,” meaning Akhmetov spent just 1 1/2 years behind bars. In June 2014, former deputy Defense Minister Bagdat Maikeyev was sentenced to six years in prison on charges of accepting some $2 million in bribes. He was released on health grounds the following February.

In an argument that echoes a position held privately by many civil servants, analyst Islam Kurayev argues that the broader population’s propensity for giving bribes helps keep the practice alive.

“You could say it cuts both ways in Kazakhstan. On one hand ‘the fish rots from the head down,” Kurayev said. “The other position could be expressed by saying: ‘that’s the tail justifying itself.’ In truth, the problem is with the general population itself, which is particularly afflicted and obsessive on this front — they give and others take.”

Meanwhile, some observers speculate that the Bishimbayev affair may ultimately just be yet another episode in the very extensive roll-call of Kazakhstan’s intra-elite squabbles, which usually culminate in one of the combatants ending up in a prison cell.

“It is true that there is a battle against corruption ‚” said Ismagambetov. “But on the other hand, there are clan groups who are using this factor to fight against their opponents. When some official or other is snatched up and thrown into jail, this is what you call ‘ditching the loser’s body.’”