WASHINGTON — U.S. President Joe Biden struck a tough note against transnational corruption during a highly promoted virtual conference he organized in December for representatives of about 100 nations.

He called it “a crime that drains public resources and hollows out the ability of governments to deliver for the people” and promised to work with partners around the world “to hold corrupt actors accountable,” including those that hide their money in the United States.

If Toqaev dumps a whole file of the [Nazarbaev] family’s holdings and dealings, does the U.S. government move forward, knowing that they are involving themselves in a domestic power struggle?

Analyst Alexander Cooley

Transnational corruption was, his administration said, now a “core national-security interest” for the United States.

Just a month since that conference ended, events 10,000 kilometers away in Kazakhstan may show the fine line the Biden administration will have to walk in trying to live up to its words.

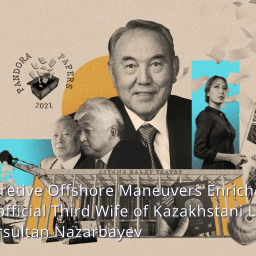

A fuel price increase at the start of the year sparked a protest in a town in western Kazakhstan that eventually morphed into a violent power struggle between President Qasym-Zhomart Toqaev and those close to his predecessor, Nursultan Nazarbaev.

After several days of mayhem that left possibly dozens dead and at least 10,000 detained, Toqaev came out on top.

And on January 11, he suddenly and unexpectedly announced the state would end a contract with a waste and recycling company connected to Nazarbaev’s youngest daughter, Aliya, perhaps the first step in a campaign to claw back the worldwide fortune of those closest to the former president.

Their wealth includes assets in the United States and Europe that, combined, are worth at least $700 million.

Analysts say the U.S. administration faces a tough decision if Toqaev takes up Biden on his promise to help hold foreign corrupt actors accountable.

“If Toqaev dumps a whole file of the [Nazarbaev] family’s holdings and dealings, does the U.S. government move forward, knowing that they are involving themselves in a domestic power struggle?” Alexander Cooley, the former director of Columbia University’s Harriman Institute and an expert on Central Asia, told RFE/RL.

“It points to some of the strategic difficulties, ethical dilemmas, and trade-offs that have to be made when you elevate anti-corruption to the highest levels of national security and foreign policy,” said Cooley, who authored a book focusing on corruption in Central Asia.

During his nearly three-decade rule, Nazarbaev put the commanding heights of the Kazakh economy — oil, gas, metals, and banking, to name a few — in the hands of his family and friends.

They largely own them through offshore companies, many of which are registered in the West. It is a structure often used by kleptocrats to protect their ill-gotten gains from seizure if and when they lose power and influence at home.

But the offshore structures — just like the physical assets in the West — also open the door for Western law enforcement to get involved and start civil or criminal cases.

Historically, it has been tough for the West to prosecute foreign corruption cases because a suspect’s home government often has no interest in assisting law enforcement.

Cooley said that was on display when the U.K.‘s National Crime Agency tried to seize three homes worth a combined $100 million that were linked to Nazarbaev’s daughter, Darigha Nazarbaeva, and grandson, Nurali Aliev, on the grounds that they could not explain the legitimate source of their wealth.

Kazakhstan backed Nazarbaeva in the proceedings, saying she was a citizen in good standing and that her wealth was legitimate, said Cooley.

Cooley said any fight to recover the offshore assets belonging to Nazarbaev and his friends is going to be “extremely messy and costly” for Toqaev.

He pointed as an example to the case of the state-owned Tajik Aluminum Company, better known as Talco, which sued its former partner Azar Nazarov in 2005, alleging he defrauded the company of more than $500 million. Talco was overseen by Tajik President Emomali Rahmon.

When the case settled in 2008, it had become one of the most expensive in English legal history, with lawyer fees exceeding $125 million. The case highlighted the extensive corruption in the nation, further damaging its already tarnished investment image.

Similarly, Privatbank, a Ukrainian-government controlled bank, has been involved in an expensive and protracted lawsuit in at least four countries against tycoon Ihor Kolomoyskiy, who is accused of defrauding the lender of hundreds of millions of dollars. Kolomoyskiy denies the allegations.

Cooley said it may not make sense for Toqaev to fight such an uphill battle. The president may instead decide to reach some sort of accommodation with the former leader’s family, he said.

Western institutions — including universities and think tanks — could become collateral damage in such a fight if a dump of financial documents shows they accepted donations indirectly from the Nazarbaev family or associates, he said. The Atlantic Council was criticized in an op-ed in 2013 for accepting money from Kazakhstan. The country does not appear on its list of donors for 2020.

Civil Society Push

Even if Toqaev doesn’t seek to cooperate with the United States, Kazakh civil society will continue to push the administration to fulfill its promise.

Members of the Coalition of Civil Society of Kazakhstan — an umbrella organization that unites various activist groups and known locally as Dongelek Ystel (Round Table) — pressed for hard-hitting sanctions against Nazarbaev’s inner circle, including family members, during a meeting at the State Department in December.

They came to the meeting armed with detailed dossiers on alleged corruption by two dozen members of Nazarbaev’s circle.

The Dongelek Ystel members, including Akezhan Kazhegeldin, who served as Nazarbaev’s prime minister in the mid-1990s, were invited to Washington to participate in forums organized by the U.S. Congress tied to Biden’s virtual conference, known as the Summit for Democracy.

With the help of Human Rights First, a U.S. nongovernmental organization, Dongelek Ystel last year filed applications with the State Department and Treasury Department requesting that they sanction six members of Nazarbaev’s circle, including under the Global Magnitsky Act.

The Magnitsky Act authorizes the president to impose economic sanctions and deny entry into the United States to any foreign person identified as engaging in human rights abuse or significant corruption.

Among the six are Timur Kulibaev, Nazarbaev’s son-in-law, and Kazakh metals billionaire Aleksandr Mashkevich, a suspect in a long-running bribery probe in Britain. Both have repeatedly denied any wrongdoing.

The activists say the United States should take action against the individuals because the alleged crimes were committed using U.S. banks.

Brian O’Toole, a former senior adviser at the U.S. Treasury Department, told RFE/RL that law enforcement cases can take years and thus foreign civil society groups tend to push for sanctions because they are “quick and cathartic.”

However, he said it may not be the best tool for the situation. Sanctions are used to achieve foreign policy goals and not simply to punish individuals.

He said other instruments, such as visa bans, may be more appropriate.

In 2021, the State Department publicly banned Kolomoyskiy from the United States for alleged corruption but did not impose economic sanctions on him, a move that could have had significant repercussions for Ukraine’s economy due to his control of key assets in the country.

Decades Of Corruption

Large-scale transnational corruption under Nazarbaev has been known to the United States since the early 2000s.

The Justice Department in 2003 charged James Giffen, an American banker and consultant to the Kazakh government, with funneling tens of millions of dollars in bribes to Nazarbaev and the head of the country’s Oil Ministry in exchange for lucrative deals for Western oil companies.

Giffen was found guilty of only a misdemeanor tax violation and a single bribery count and faced no more than six months in prison.

The United States has ramped up the use of sanctions to deter and punish malign activities, such as human rights abuses and corruption, committed by foreign governments and individuals.

Kazakhstan and its elite have been spared to date, despite their poor track record on both accounts.

Some analysts have criticized the State Department’s reaction to the violence against protesters in Kazakhstan as weak.

William Courtney, who served as the U.S. ambassador to Kazakhstan in the early 1990s, told RFE/RL that the West has been cautious to criticize Kazakhstan’s leadership over the years “because they have cooperated in so many areas,” including nonproliferation and energy.

He said he expected the United States to first see how things develop in Kazakhstan before contemplating any action against individuals. Like Cooley, he said imposing sanctions now for violence or corruption could be interpreted as the West trying to influence the power struggle.

O’Toole said Washington’s main priority with respect to Kazakhstan over the next year is to make sure it stabilizes following the recent upheaval.

Original source of article: https: https://www.rferl.org/