The battle over fugitive billionaire Mukhtar Ablyazov stretches from Kazakhstan to Knightsbridge

1. The Kazakh connection

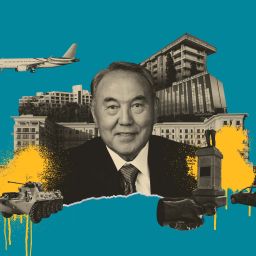

In 2009, a fugitive Kazakh oligarch arranged a meeting in London with the head of an international private intelligence agency. Mukhtar Ablyazov, a slim man in his mid-forties with receding hair, a delicate mouth and a flinty gaze, had fled to the UK earlier that year as the Kazakh government prepared to nationalise his bank. So much money had gone missing from that institution that Ablyazov’s enemies would call him the Bernie Madoff of the steppe.

But the chess-playing billionaire was also one of the few members of the Kazakh elite who had dared to cross Nursultan Nazarbayev, the former Soviet republic’s ruler since 1989. The allegations of grand looting were, Ablyazov maintained, merely a vendetta waged by a regime that was itself gorging on stolen wealth. He had broken the code of loyalty — a transgression that Nazarbayev would not, he believed, allow to pass unpunished. “I saw the spies around me and I wanted to hire a group to counter what the spies were doing,” Ablyazov told me recently.

The man that Ablyazov was to meet was Ron Wahid, the Bangladeshi-American founder of Arcanum Global. Wahid swathes Arcanum in mystique — its name comes from the Latin for secret — but he also likes to show off his political connections. On the walls of his Knightsbridge offices hang signed photographs of him with three US presidents.

People who have dealt with him say he peppers conversation with hints that he worked with US intelligence agencies before setting up Arcanum in 2006, although the biography on the company website makes no claim of any formal role. Superstar spies have graced Arcanum’s board, including the late Meir Dagan, former head of Mossad.

Ablyazov and his associates say Wahid gave them the hard sell. He portrayed Arcanum as “some sort of super service that has super resources at their disposal”, Ablyazov remembers. Wahid’s staff would bring phone-jammers to the meetings to prevent eavesdropping, a precaution Wahid says he routinely uses but that Ablyazov took to be “them

Wahid already knew something of the baroque power struggles that spill out of Kazakhstan, a resource-rich Central Asian expanse of nomads and billionaires that forms a strategic fulcrum between Russia and China. Arcanum’s previous clients had included Nazarbayev’s estranged son-in-law. An Ablyazov associate who attended some of the meetings recalls that Wahid “says he knows everybody in the Kazakh elite”.

Wahid — a portly man who travels by private jet, mixes with the glitterati and says some of his staff enjoy “above-topsecret” security clearance from the US government — belongs to a booming industry. It extends from CIA contractors to masters of propaganda, from the offshore accountants who launder ill-gotten wealth to the sleuths who try to follow the money.

Its practitioners are often investigators by trade — former spies, prosecutors and journalists — but they also include lobbyists and establishment luminaries. For handsome fees, teams from this largely unregulated industry will set about the extraction, dissemination and, sometimes, manipulation of information to serve a client’s agenda and target that client’s enemies — enemies who have, often, assembled a similar team of their own.

The industry’s currency is secrets. Its services range from tracing fraudsters’ assets to darker arts that include hacking, infiltration, honey traps, blackmail and kidnapping. On the front line are the private intelligence agencies. Some of them have benefited from the growth in outsourcing by the law enforcement and spy agencies of the US and its allies — the source, Wahid says, of almost all Arcanum’s work.

But many firms have amassed expertise and tradecraft once monopolised by state agencies and put it at the service of tyrants, oligarchs and anyone else willing to pay. Their critics say they have no friends, only invoices, but many in the business see themselves as soldiers of justice in a globalised world, filling a vacuum left by enfeebled states and cashstrapped, antiquated law enforcement.

The industry is concentrated in the west because that is where the money is. Since the end of the cold war, the offshore system has helped a growing cohort of kleptocrats and their cronies to channel dubious fortunes into western markets.

Officials in western Europe and North America say billions of dollars in dirty money pour in each year, mainly through assets such as real estate. London, long a city of secrets, is the industry’s capital. Many firms have taken offices in Mayfair, the exclusive, cosmopolitan quarter where wealth and politics mix.

The Ablyazov case mirrors the “tournament of shadows” fought in the 19th century by spies, soldiers and fortuneseekers from imperial Russia and Britain in an attempt to control Central Asia. Today, though, the political battles of the former Soviet Union are fought not in the parched valleys east of the Caspian but in western courts, parliaments and media.

Dictators’ representatives tirelessly curry favour at Westminster and on Capitol Hill. Oligarchs are fixtures in London’s High Court listings. Rare is the business journalist who has not spent lunch listening to the PRs of one recently minted billionaire smear another recently minted billionaire.

In the trade, a covert attempt to blacken a target’s name is known as ‘Black PR’

As they sized each other up in 2009, Ablyazov says he asked Wahid to prove his worth by providing some valuable intelligence against Nazarbayev, but Wahid only offered documents that Ablyazov had already acquired. (Wahid disputes this.) Ablyazov grew suspicious that Wahid was, in fact, playing a double game and working for Nazarbayev’s regime. As he listened to descriptions of Arcanum’s services, he started to think that the meetings were a trap designed to lure him into illegal activity in the UK, where he had claimed asylum, and decided against hiring the firm.

“We never gave them a proposal for fighting Nazarbayev but, yes, we were working for Kazakhstan at this time,” Wahid told me. The two sides had “a general discussion of our capabilities”, he said. But Wahid insisted that Arcanum In the trade, a covert attempt to blacken a target’s name is known as ‘Black PR’ never does anything illegal. Ablyazov’s suggestion to the contrary — part of a narrative in which Arcanum is key to Nazarbayev’s campaign of persecution — was a “fantasy”, Wahid said.

Those London meetings represented the early exchanges in perhaps the most remarkable battle the secrets industry has yet fought. A Financial Times investigation based on 30 interviews and thousands of pages of court documents, leaked emails and confidential contracts exposes a saga in which Arcanum is just one piece on a chessboard that spans four continents. It reveals how the mercenaries of the information age are shaping the fate of nations.

Born in 1963 to a family of modest means in a Kazakh village near the Russian border, Ablyazov ditched a promising career in nuclear physics to embrace the Wild West capitalism that took hold as communism collapsed.

Across the former Soviet Union, immense riches were available to those with connections and guile.

“There were no laws,” he recalls. “I got into business by chance.” By importing photocopiers, fax machines and computers, he rapidly made enough to buy a house for his young family. He cultivated a ruthless streak and by 1998 he was one of the richest men in the land, worth some $300m. He was also a leading member of a consortium that won a privatisation auction with a $72m bid for what would become BTA Bank.

The man at the top of the tree, however, was the same man who had been in charge in the Soviet days: Nazarbayev. As the authoritarian with a rictus smile cemented his power, those close to him made fortunes. Petrodollars that poured in from Kazakhstan’s Caspian oilfields went astray. A US corruption investigation in 2003 turned up what prosecutors said were Swiss bank accounts controlled by Nazarbayev containing $85m of bribes.

“There’s not one member of this [Kazakh] elite that did not gain from the transition from the state-owned planned economy to the market economy,” says Yevgeny Zhovtis, one of Kazakhstan’s few prominent human rights activists. “Either illegally or semi-legally, they became millionaires and billionaires.”

By the turn of the century, Ablyazov had started to mix politics with business. He became minister of energy in 1998 but resigned the following year. Nazarbayev summoned Ablyazov to his residence. “When I came in, he immediately started ranting at me,” Ablyazov recalls. He says that, when he criticised the president for laying the foundations of a “clan-ocracy” and declined to rejoin the government, Nazarbayev responded: “Well, in that case, you’re going to have to give me a chunk.”

In Ablyazov’s telling, the president wanted half of BTA Bank’s shares transferred to his nominees, to ensure the businessman’s loyalty. No such deal was reached and relations deteriorated further when Ablyazov and some 20 others announced the formation of Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan in 2001. Although its stated aim was incremental reform, Nazarbayev saw the party as an intolerable threat.“

Following what Zhovtis calls a “selective prosecution” for abuse of his government office, Ablyazov was jailed in 2002.

He emerged from a prison camp in 2003 after promising Nazarbayev that he would refrain from politics, but he soon began covertly funding opposition groups. He had retained his interest in BTA Bank, held on his behalf by a trusted associate, and in 2005 he became chairman, overseeing rapid expansion across the region.

When the financial crisis struck, the Kazakh authorities declared that BTA was close to collapse — exaggerating its difficulties, Ablyazov says, in order to fulfil Nazarbayev’s long-held aim to seize the bank. In January 2009, as it became clear that the government was preparing to nationalise BTA, Ablyazov fled to London.

The Kazakh authorities say that, once they started to go through BTA’s books, they found it was missing enormous amounts. Legal proceedings to date have put the figure at $4.2bn. Much of the money was owed to western banks, including RBS, which had been bailed out by the UK taxpayer. Huge sums appeared to have flowed out to offshore companies whose owners were hidden.

The private investigator whom BTA Bank recruited to track down its missing billions was an ebullient former member of the British military’s elite Special Boat Service. Trefor Williams works for Diligence, a corporate intelligence firm whose smart London offices he has decorated with James Bond posters. Williams is muscular, with a lilting North Wales accent. He has spent so long hunting Ablyazov and his wealth that he refers to him almost fondly as Mukhtar.

Williams and his team watched as Ablyazov came and went from Carlton House, a mansion on Bishops Avenue, the Highgate street known as Billionaires’ Row (two doors along from one reportedly owned by Nazarbayev). They were looking on as Ablyazov and his associates — Britons among them — convened frequently at an office in the heart of the City. “All these people could have worked from home and our job would have been much harder,” he told me. “But they need a semi-legitimate gathering point. A lot of the time, it’s their downfall.”

In October 2010, Williams’s bloodhounds followed one of Ablyazov’s brothers-in-law to a self-storage facility in Finchley, north London. BTA’s lawyers secured a court order to open the container. Inside, among 25 boxes of documents and a hard drive, was a spreadsheet listing some of the thousands of offshore companies through which BTA’s billions had flowed, a virtual treasure map of secretive tax havens. It was the key to what Williams describes as the biggest money-laundering operation he had encountered.

Williams’ sleuthing provided ammunition for Chris Hardman, an aggressive lawyer with the London firm Hogan Lovells. Hardman used evidence from the storage unit and other finds to show flows of money from his client, BTA Bank, to the offshore vehicles of its former chairman. In the Gothic splendour of London’s Royal Courts of Justice, Hardman racked up judgments against Ablyazov that would exceed $4bn. One judge said of the Kazakh oligarch’s attempts to conceal his ownership of assets: “It is difficult to imagine a party to commercial litigation who has acted with more cynicism, opportunism and deviousness towards court orders than Mr Ablyazov.”

Ablyazov maintains that he is the victim of a strategy, common in former Soviet states, of deploying commercial litigation to crush political opponents — using the world’s most respected courts to confer legitimacy. He says his extensive use of financial subterfuge is not a means to abet the amassing of illicit wealth but to prevent it.

In a 2010 witness statement, he said: “In Kazakhstan the assets of wealthy individuals such as myself are subject to the threat of unlawful seizure by the authorities… This leads to an almost universal practice among high net worth Kazakhstanis of holding our assets through nominees, both corporate and individual.”

In February 2012, a British judge ruled that Ablyazov’s concealment of assets that should have been declared under a freezing order left him in contempt of court. He sentenced the oligarch to 22 months in prison. But Ablyazov would never enter a British jail. He had vanished

For a country of 18 million people with an economy about half the size of Ireland’s, Kazakhstan has made a disproportionately large contribution to the private intelligence industry. Through the noughties, as its oligarchs poured their fortunes into western assets and listed their companies on western stock exchanges, their appetites and rivalries made lucrative work for these secretive firms. “At one point, literally everyone I know in London was working on Kazakhstan,” says a private investigator who worked on several Kazakh dossiers. Another says all the money pouring in from the former Soviet Union helped to make the private intelligence game in London “very dirty”.

The British capital, for centuries an entrepôt for spies, moneymen and emissaries, has become the industry’s heart but the archetypal corporate intelligence firm was founded in New York. In 1972, Jules Kroll took skills he had honed exposing those who demanded kickbacks from the family printing business to found what became Kroll Inc. After 32 years of hostile takeovers, hostage negotiations and everything in between, Kroll sold the business for $1.9bn.

By then, rivals had sprung up. Some had links to private military contractors that profited from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Others were founded by CIA or MI6 alumni. The big accountancy firms, including EY, Deloitte and PwC, set up corporate investigations arms. Scores of small outfits emerged, specialising in particular regions or techniques. Some companies fused sleuthing with propaganda, another boom industry. In 2006, FTI Consulting, a US investigations group, paid $260m to acquire the City PR firm Financial Dynamics.

The corporate intelligence industry’s bread and butter is “due diligence”, background research commissioned by one company into another that it wants to buy or do business with. Sometimes the work is shoddy; one mergers and acquisitions lawyer recalls being presented with “a page of googling”. But some investigators have such intimate knowledge of their specialist areas and impeccable sources that they complain of giving their clients more information than they want to hear.

A by-product of all this is mountains of dirty laundry of the most powerful — and nefarious — business figures and their political allies. The firms have become the keepers of globalisation’s secrets. And they have wound up in the middle of some of the most colourful intrigues of recent years. Neil Heywood, a British businessman poisoned by the wife of a powerful Chinese politician in 2011, had advised Hakluyt & Co, private investigators based in Mayfair. In January this year, a former MI6 officer called Christopher Steele went into hiding after being exposed as the author of a dossier of allegations about Donald Trump’s Russian connections, commissioned by Fusion GPS, a US investigations agency.

Some in corporate intelligence see a higher purpose for their endeavours, helping to uncover the machinations of the rich and powerful. But others are queasy. Aaron Sayne, a former US corruption lawyer who now conducts corporate investigations, says many in his field “hoover up sensitive information and use it for one purpose on day one and some completely contradictory purpose on day two”.

He adds: “There are a lot of people who are walking a very fine line between investigations and public relations. They are doing investigations and it’s very quickly being spun or turned into muckraking. You see people starting to play faster and looser with the truth.”

The Ablyazov case has been a feeding trough for corporate intelligence. Some firms have made millions, among them Arcanum. True to its name, Arcanum is less than forthcoming about its work. What public announcements it makes largely relate either to polo, Ron Wahid’s abiding passion, or to the latest appointment of a retired military or intelligence heavyweight to its board.

Half a dozen private investigators and lawyers with knowledge of Wahid’s work describe a man who cultivates an air of mystery but whose own intelligence credentials are unclear. One US intelligence operative who has encountered Wahid says he was “stone cold CIA” but a former spy who has heard him discuss intelligence matters is sceptical: “He likes to say he’s an ops guy, but the way he talks, you can tell it would never have been like that.”

Another person with deep connections in the CIA and other US agencies says Wahid is “known to people in the intelligence community” but suggests that his access is partly the result of his largesse. Wahid’s recent political donations include $376,580 to Jeb Bush’s 2016 presidential campaign and $100,000 towards Donald Trump’s inauguration. In a 2015 corporate filing, Wahid describes himself as an “entrepreneur”.

When we meet at his Knightsbridge office in August, Wahid is dressed in a grey suit. By the door stands a silver chessboard on a mounting shaped like a fist. Leaning back in his chair, Wahid tells me there are governments he would not work for, naming Russia and China. I ask how he came to deem Kazakhstan an acceptable client. He gives a practised analysis. “Despite allegations of a lack of democratic process, President Nazarbayev has done an incredible job in maintaining security and stability in a country that previously had nuclear weapons. He has been extremely useful to the US in our operations in Afghanistan and in nuclear peace. After the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s the only country that has stability.”

Wahid says his world view is inspired by Ronald Reagan’s crusade against communism. Arcanum says it has worked with the FBI, Interpol, New Scotland Yard and the US justice department. Wahid declined to specify any of these cases. I asked each of the agencies if they would confirm that they had worked with the firm but none of them did. Ablyazov says Arcanum is “certainly in the upper echelons of the spy agencies that have done work against me”.

Emails seen by the FT, which Wahid does not dispute, show Arcanum charged Kazakhstan $3.7m for work up to the end of 2012 alone. Wahid confirms what the emails suggest: that Arcanum reports to some of Nazarbayev’s most senior officials while being formally commissioned, at various times, by Kazakhstan’s foreign lawyers, including City firm Reed Smith as well as US and Swiss firms. I ask what Arcanum has done for Kazakhstan in its pursuit of Ablyazov since those meetings in 2009. “Asset tracing,” Wahid says, as well as “developing the legal strategy and dealing with inter-agency co-operation.”

When Ablyazov went to ground to avoid prison in the UK, those pursuing him and his money started to pay closer attention to his associates. Chief among them was another exiled Kazakh businessman, Ilyas Khrapunov, who is married to Ablyazov’s daughter. Kazakhstan accuses him of being a key lieutenant in a worldwide operation to stash clandestine wealth, including his father-in-law’s, in assets ranging from a luxury Swiss hotel to US real estate linked to Donald Trump.

Switzerland has declined to extradite Khrapunov and his relatives — so, Khrapunov says, Kazakhstan has come to Switzerland looking for them. In correspondence with the Swiss authorities, the Khrapunovs’ lawyers say that the family and its representatives have been subjected to a surveillance campaign that amounted to illegal espionage, including bugging and a barrage of booby-trapped emails. They name Arcanum among the agencies they believe have played a role in this campaign against them. In 2014, the Swiss authorities launched a criminal investigation into the matter.

I asked Arcanum about the Swiss investigation and was told it had never broken Swiss law and enjoyed “a very good working relationship with Swiss authorities”. The company said: “Swiss prosecutors did not lodge any complaints against Arcanum as their examination found the accusations baseless.” The Swiss attorney-general’s office told me that, after the Khrapunovs won a court ruling in 2016 overturning a decision to suspend the probe, the investigation resumed and is “ongoing”. It declined to give further details.

Wahid accepts that his investigators have interrogated former employees of the Khrapunovs — though he denies claims made in a sworn statement by Ilyas’ former secretary that an Arcanum investigator gave her the impression he could get her immunity from criminal prosecution. And while Wahid declines to discuss the matter, five people familiar with it say that Arcanum played a role in persuading at least one of the fixers in Ablyazov’s alleged moneylaundering network to switch sides.

Ablyazov’s supporters say that Arcanum is a cog in a “repression machine” that the Nazarbayev regime has assembled in order to extend its power beyond Kazakhstan’s borders. “Absurd,” counters Wahid. “To assert that our work supports ‘repression’ would mean you claim that the UK, French, Swiss and US governments and laws are complicit with Kazakhstan’s ‘repression machine.’” He adds: “Our work is purely strategic and not operational. We don’t go digging in people’s trash. Other firms might do that.”

In private, many of the investigators in the Ablyazov affair took Wahid’s line that their work has been beyond reproach but that others may have gone too far. Likewise, western consultants and Kazakh officials blame each other for adopting outlandish tactics. As the hunt for Ablyazov spread across Europe, it left a trail of questionable methods, triggering scandals or criminal investigations in at least six western countries. The alleged offences range from improper interference in the judicial process to illegal espionage and kidnapping.

In December 2012, a few months after Ablyazov disappeared, Aleksandr Pavlov, his bodyguard, was arrested as he arrived in Spain. The Kazakh authorities sought his extradition to face allegations of assisting Ablyazov’s grand theft and plotting a terrorist attack that was never carried out. A Spanish court refused Pavlov’s asylum application but the dissenting judges wrote that “we find ourselves faced with a political persecution, under the guise of a claim for common crimes”; they warned that Pavlov might be tortured in Kazakhstan. Pavlov appealed and his case dragged on; there were allegations that Kazakh officials interfered with the Spanish judicial process.

Pavlov’s detention came after Kazakhstan had put out an Interpol alert for him following Ablyazov’s disappearance from Britain. These Red Notices are designed to assist international co-operation in the apprehension of fugitives. But their deployment, by the Russian government and others, against political enemies is starting to undermine the Interpol system. In March this year, the parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe issued a resolution condemning the abuse of the Interpol system for political ends.

Among a list of examples, it declared that “dozens of family members and supporters” of Ablyazov were “being persecuted, including through Red Notices”. Interpol would not comment on the Ablyazov case but said that although

the “overwhelming majority of Interpol Red Notice requests by member countries raise no issues at all”, it had “comprehensively overhauled and enhanced all its supervisory mechanisms” in the past two years.

Pavlov eventually won asylum in Spain. But the search for his boss went on.

In March 2013, Amit Forlit, an Israeli private investigator, commissioned an Italian detective agency called Sira Investigazioni. The fee would be €5,000, according to a letter seen by the FT, and the task to locate a residence believed to be used by Ablyazov in the leafy Roman suburb of Casal Palocco. The detectives appear to have delivered the goods. Six weeks later, a Kazakh police bureau transmitted a message to its counterpart in Rome requesting that Italian officers raid an address there. On May 29, they did so.

Ablyazov was not there but his wife, Alma Shalabayeva, was, bearing a diplomatic passport issued by the Central African Republic. She was taken into custody. Two days later, agents arrived at the house where the couple’s six-yearold daughter had been staying since her mother’s detention. A pair of Kazakh diplomats escorted mother and child on to a private plane. Within hours, they were in Kazakhstan.

In Italy, outrage ensued. The deportation was declared unlawful; the office of the UN’s high commissioner for human rights called it an “extraordinary rendition”. In mid-July, Enrico Letta, then prime minister, said it had brought “shame and embarrassment” on the nation. Kazakh authorities released the pair, who returned to Italy and were granted asylum. A criminal case for kidnapping against Italian officials, police officers and, in absentia, the Kazakh diplomats involved began in September this year. (Forlit did not respond to requests for comment; Sira declined to comment. Neither has been charged.)

While this unfolded in Rome, Trefor Williams — who, like Wahid, says he had nothing to do with the kidnapping — was still trying to locate Ablyazov for BTA Bank. After 18 months of false leads, a Ukrainian lawyer who attended a London court hearing caught the attention of Williams’ team and led them to France. Deploying a sleuth in a bikini and another who spent hours shuffling over a zebra crossing to allow a close inspection of passing vehicles, the Diligence bloodhounds homed in on a mansion near Cannes. It proved to be Ablyazov’s opulent hideout. They alerted the police, who in July 2013 sent in an armed unit, apprehending Ablyazov and taking him to a nearby jail.

Kazakhstan has no extradition treaty with France but Russia and Ukraine do. Each had charged Ablyazov with financial crimes related to BTA Bank; they asked France to hand him over. The western front of the war between Nazarbayev and Ablyazov was approaching its climactic battle. Now, more than ever, the side that could control how Ablyazov was perceived would have the decisive advantage.

Tell that c*** you work for that we’re bringing him and all this criminal shit down around his ears

PATRICK ROBERTSON, WORLD PR

The British capital is seen by many as the heart of the private intelligence industry. According to one investigator: ‘At one point, literally everyone I know in London was working on Kazakhstan’

At five minutes past midnight on August 27 2015, Peter Sahlas’ phone chimed. Sahlas, a Canadian human rights lawyer, is boyish in looks but tenacious in his work. He has worked on Ablyazov’s case since the oligarch first fled to London. One lawyer on the other side accuses him of ignoring the evidence of malfeasance with “Nelsonian blindness”. But Sahlas is adamant that he would not have spent long years fighting — sometimes unpaid — if he did not truly believe in his client. “Some things are more important than money,” he says, “like when a client’s case is a matter of life or death.”

The message was from a number Sahlas did not recognise. “Dear Peter Sahlas,” it began, “please tell that bald-headed c*** that you work for that we are bringing him and all this criminal shit down around his ears.” It went on for a few more lines, then concluded: “And just to be clear, you Quebec piece of shit, you are going to lose your shirt along the way. Have a fun time.” It was signed “PR”.

Baffled, Sahlas responded. “Hello, sure, I will pass on your message,” he wrote. “But who is it from?” The reply came: “Patrick Robertson. Have that name etched on your collective memory.”

During a 25-year career as what he calls a “strategic communications adviser”, Patrick Robertson has sought to burnish the image of figures such as the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and the disgraced British politician Jonathan Aitken. He is well-connected among the Conservative establishment: Margaret Thatcher was honorary president of the Bruges Group, the Eurosceptic organisation he co-founded in 1989.

The website of World PR, Robertson’s Panama-registered firm, carries a quotation from an otherwise disparaging article in the London Evening Standard: “Patrick Robertson’s energy and entrepreneurial skill is phenomenal. He is a very modern figure. He understands networking and the power of the media. He has charm and a remarkable ability to make people trust him.” The website also calls Robertson “a key player in Kazakhstan and Central Asia”.

Kazakhstan under Nazarbayev has hired a long line of propagandists to tend its image. Corruption scandals have hampered the leader’s efforts to be seen as a statesman, as have election victories in which he scored more than 90 per cent, laws that effectively facilitate money-laundering and evidence of widespread torture by security services.

The Kazakh elite appears to have a taste for the master communicators of British politics. When police responded to an oil workers’ strike in 2011 — one supported by Ablyazov — by shooting dead at least 12 protesters, the president took advice from Tony Blair on a speech to manage the fallout. (Blair’s Institute for Global Change told me: “Our consistent advice was that the government should establish a full and thorough independent investigation on the events.”) When Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation, a Kazakh mining house that listed on the London Stock xchange in 2007, became engulfed in allegations of corruption, a senior Kazakh official took soundings from former Labour minister Peter Mandelson.

Ablyazov believes he’s the most clever person and that he will get away with it

MARAT BEKETAYEV, KAZAKH JUSTICE MINISTER

In the battle of perception with Ablyazov, Kazakhstan has turned to top-of-the-range London PR outfits.

Portland Communications, founded by Tim Allan, a former deputy press secretary to Blair, picked up the BTA Bank account. Shortly after Ablyazov was granted asylum in the UK in 2011, someone using a Portland IP address altered his Wikipedia page, until a moderator noticed and cried foul.

Portland told me “the changes were carried out in order to correct inaccuracies… designed to distort the truth about Ablyazov’s fraudulent activities”. It said “no attempt was made by Portland to deceive or to disguise the origin of these changes” but that, after its work was discovered, it trained its staff in “the most up-to-date standards”, including a visit from Wikipedia’s founder.

By the time of Ablyazov’s capture in France, the kidnapping in Italy and other scandals had tainted the perception of Kazakhstan’s motives. In early 2014, as Ablyazov prepared to appeal against a French court ruling that he could be extradited, confidential memos for senior Kazakh officials outlined a strategy proposed by FTI Consulting. “MA’s objective will be to win public opinion,” FTI said, recommending a counter-attack.

As well as cultivating French MPs, FTI discussed using “search engine optimisation” so Google results for Ablyazov would be more likely to say “fraudster” than “dissident”. And it proposed paying a Swiss non-governmental organisation for an ostensibly independent report condemning Ablyazov. The NGO, the Organised Crime

Observatory, told me it turned down the offer. FTI declined to comment.

In the trade, a covert attempt to blacken a target’s name is known as “black PR”. One practitioner defines the tactic as “putting [out] the negatives of your opponents, without any fingerprints”. In extreme form, it has shaken whole nations, such as South Africa, where the discovery of a campaign that stirred racial tension recently brought down the celebrated British PR firm Bell Pottinger.

On the face of it, Patrick Robertson’s work for the Kazakh PR campaign against Ablyazov was straightforward.

Correspondence seen by the FT shows that in mid-2014 BTA Bank agreed a £3.25m contract for World PR to make and distribute a documentary painting Ablyazov as his enemies in Kazakhstan wanted.

However, Peter Sahlas came to suspect that there was more to Robertson’s role. After Robertson contacted him, Sahlas trawled a trove of official emails that had been published online — the so-called Kazaword leak that the country’s authorities blame on Ablyazov’s associates. He found correspondence from early 2014 in which Robertson arranged to meet a top Kazakh official in Washington. There was nothing unusual about that, except for a strange email dating from the same time. It contained an unsigned memo proposing to use research for a documentary as a cover for espionage against the “Little Man”.

This would involve “covert operations” subjecting Ablyazov and his entourage to “cyber assaults” and “sabotage”.

There would be “media manipulation globally”. The proposal went on: “We will be contacting everyone whether they be friend, associate, family member in Little Man’s life and he will find that we are in every aspect of his existence, further undermining his confidence.”

Sahlas noticed that the text of the email was written in the same distinctive font that World PR uses (although that could easily have been copied). The sender’s Gmail account appears as “Peter Ridge”, a name no one involved in the affair seems to know. The email had been initially sent to a private account apparently belonging to a top Kazakh diplomat. The diplomat sent it on to the leading Kazakh official that Robertson had arranged to meet in Washington days later with the message that it was “in relation to your meeting in DC”.

Either Robertson was behind this proposed strategy or someone has tried to make it appear that he was. Sahlas says that he and others close to Ablyazov have been subjected to some of the tactics described in the “covert operations” email — including by the makers of an unflattering documentary on Ablyazov.

I asked Robertson whether he wrote the email under a pseudonym. He told me: “We never comment on any aspect of our work for our clients, so I will not do so on this occasion. However, since the fact of our client relationship with BTA is online (as a result of an unfortunate leak), let me be clear: the contents of the document you have asked me to comment on bears no resemblance to the contract that we signed with BTA Bank.”

Robertson’s SMS exchanges with Sahlas went on for three months. They ranged from foul-mouthed threats to invitations “to start negotiations on bringing you covertly on to our side”. In his final message, in October 2015, Robertson left open the offer “to arrange your exit from that cesspit you’ve attached yourself to”. Sahlas did not take up the invitation. A few months later, he and his client would score a spectacular victory.

Astana, the capital that Kazakhstan’s rulers raised out of the steppe, has the feeling of a settlement that grew by command rather than the gradual accumulation of humanity. The streets are clean and orderly; the grass verges enjoy constant tending. Architect Norman Foster’s vast, sloping yurt gleams at one end of the main boulevard. All around are five-star hotels and western fast-food chains.

Marat Beketayev, the justice minister, belongs to the young, cosmopolitan generation of Kazakh leaders whose stated goal is to turn a land that has endured centuries of subjugation into a modern, confident state. Before our interview, he shows me a corridor bearing portraits of his predecessors, pointing out two from the 1930s whose tenures ended when Stalin jailed them.

Beketayev only turned 40 in August. He has risen fast. In a mellifluous voice, he explains that he grew up in a village where most jobs were in the three Soviet prisons nearby, one of which was run by his father. Perhaps, he accepts, that explains his interest in the law.

Beketayev has been at the heart of the Nazarbayev’s government’s efforts to use western legal systems to bring down Ablyazov. “Really what Kazakhstan wants is to make sure that criminals and corrupt people who want to steal money in Kazakhstan and go abroad don’t get an opportunity to launder the money with the help of lawyers,” he says. Kazakhstan’s lawyers and lobbyists urged agencies such as the UK’s Serious Fraud Office to open criminal investigations into Ablyazov, to no avail. “We understand the limits of public expenditure, we understand all the constraints, but we want them to do more, because only working together can we achieve proper relations.” Calmly but firmly, he adds: “We really want London to do more in order to make sure that all the money coming to London is clean.”

With the authorities in London and elsewhere in the west seemingly unwilling to go after the illicit money flows from which their economies were benefiting, Beketayev says that Kazakhstan had no choice but to do the job itself. I ask about Ron Wahid. “What we think is valuable in our relationship with Arcanum is their knowledge and expertise because they hire people from former law enforcement and from intelligence. These are the people who have worked with such criminals for their whole lives.”

And why the need for all the propagandists? “Because, I think, we were losing this PR war.” I ask about the proposed “media manipulation” strategy and Patrick Robertson’s role. “He may think that we were interested in such things,” the minister says. “I only met him several times. I don’t remember him proposing such an approach.” He went on: “It is funny for me to hear that we could be regarded as people who are able to use such mechanisms and such methods.”I ask why that’s funny.“ It’s not the way we’re used to working.

Beketayev was the official who met Robertson in Washington and to whom the mysterious “covert operations” email was sent. After our interview, I asked Beketayev’s office some questions about it. The reply said: “We do not comment on information that was obtained by illegal and unlawful means. Anyone reading that information should bear in mind that it may have been manipulated.”

Other correspondence seen by the FT, as well as interviews with investigators involved, indicate that, in parallel with BTA Bank’s pursuit of its missing billions, Beketayev has directed an intercontinental strategy against Ablyazov. He has liaised with Reed Smith, Kazakhstan’s long-standing London lawyers, PR and intelligence agencies, including Arcanum, and western politicians.

Asked about the more outrageous tactics mooted by some of the consultants on Kazakhstan’s dollar, Beketayev suggests that western agencies saw working for a post-Soviet republic as an opportunity to indulge in the dark arts.

“Frankly, there were many people approaching us with such proposals.” The techniques on offer were “disturbing, arranging some kind of scandals, hacking emails, things like that. This is simply stupid. This works maybe for a short period of time but, in the long run, if you engage in such things, you will never be taken seriously by other countries.”

Kazakh dissidents and international human rights activists who support Ablyazov’s cause argue that, even if he did improperly divert money, he is guilty only of playing by the kleptocratic rules that govern the Kazakh elite. I put it to Beketayev that while Ablyazov has been relentlessly pursued, pro-regime oligarchs with dubious pasts have prospered. “It is true that there was a period of time when it was possible to get away with crimes,” he says. “And step by step, this time is going away. We’re a young country. When the Soviet Union collapsed, there were no legal mechanisms whatsoever. But still it was possible for us to keep general order and because of general order, because of the strong power of the president, we had a stable time to develop.”

I relay Ablyazov’s argument that he was forced to use offshore secrecy to protect his fortune. “It’s a nice story from him because he wants to keep his stolen money and any other story wouldn’t stand. He has nothing else to say and he’s not the first person to use the political opposition card in order to protect himself from criminal prosecution. But when you see examples of opposition leaders, how many of them live in luxury villas in the south of France? How many of them give money to their children in order to invest in a development project in New York, a development project in Geneva?”

Dusk is falling over the glitz of Astana. I ask what Beketayev makes of Ablyazov himself. “I personally believe that this guy is mad,” he says. “He’s not afraid of being caught because he believes that he’s the most clever person and he will get away with it.”

Ablyazov’s family and lawyers were on tenterhooks as December 9 2016 dawned. Ablyazov had spent three years in French prisons. Later that day, the Conseil d’Etat, France’s highest court for such matters, would announce its decision on whether he should be extradited to Russia.

The odds were not good. The French prime minister, Manuel Valls, had approved the Russian extradition request, which had taken precedence over Ukraine’s. Only once before, in 1977, had the Conseil d’Etat denied an extradition request on the grounds that it was an attempt to use criminal allegations for political ends. Ablyazov would be a sitting duck in a Russian jail, his people feared. Moreover, they considered Russian assurances that it would not hand over the captive to Astana to be worthless.

Russian prosecutors had opened their own investigation into Ablyazov’s activities in their country, where BTA had a subsidiary. Many of the real estate projects that had allegedly helped to drain the bank were based there but Ablyazov’s teams argued that the investigation amounted to political persecution at Kazakhstan’s behest.

Ablyazov’s lawyers say seven investigators and other officials involved in the Russian case had also had a hand in the Sergei Magnitsky affair, in which the young auditor and lawyer died in prison after exposing corruption, prompting US sanctions against those deemed responsible. And leaked emails suggested that representatives of Nazarbayev’s regime exerted influence over the criminal probes into Ablyazov and his associates in Russia.

In France, too, Ablyazov had cause to be unnerved. Arcanum had hired Bernard Squarcini, chief of domestic intelligence during Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency. Days before the extradition hearing, an investigating magistrate, who was probing whether Squarcini had improperly put his old intelligence contacts at the service of private clients, had written to Ablyazov informing him that he may have been a victim in the case.

Ablyazov’s team prayed that France would not follow the UK example. Lawyers and lobbyists working for the Kazakh government had repeatedly asked the UK to rescind his asylum, a status that helped to validate his arguments. In January 2014, the British government informed Ablyazov of its intention to do just that. A memo by Reed Smith reported that John Howell, a consultant working for the Kazakh government, considered that the government’s move was “being driven by the [then] home secretary, Theresa May, as part of a wider ‘clean-up’ of asylum decisions that have been taken in recent years in respect of individuals who have abused the system and rules”.

It’s a slap in the face to the PM of France. It’s a slap in the face to Putin. It’s a slap in the face to the Kazakhs

PETER SAHLAS, LAWYER

Ablyazov’s refugee status was “considered to be a problem for UK-Kazakh relations and there is a pro-Kazakhstan push by David Cameron, who is keen to drive the relationship forward”. The previous year, Cameron had become the first UK prime minister to visit Kazakhstan, signing contracts worth £700m. (The Home Office and Howell declined to comment; Reed Smith did not respond to a request for comment.)

As the judges started to deliver their findings, Sahlas listened intently for signs of which way the court would go. Then, he recalls, he heard the words: “Mutual confidence does not mean mutual naivety.” He felt a thrill. The court reversed the prime minister’s decision to grant Russia’s extradition request. Sahlas told me afterwards: “It’s a slap in the face to the PM of France. It’s a slap in the face to Putin. It’s a slap in the face to the Kazakhs. Jurisprudentially, it’s an earthquake.”

In Astana, Beketayev detected ulterior motives in this decision taken at a time of the worst crisis of relations between Moscow and the west since the cold war. “I think this was about — and I have to be careful here — this was not more about Ablyazov, this was more about global politics,” he told me.

Ablyazov travelled from prison to a rented apartment in Paris for a hearty meal of Kazakh pilaf. He picked up his guitar and sang the song he performs in moments of triumph, a number about cheating death. Then the fightback began.

The intermediary who brought me to my meeting with Ablyazov in April followed a circuitous route to ensure we were not tailed to his comfortable apartment. The oligarch’s associates fear that, following their victory in the courts, the risk of an assassination — the last resort of post-Soviet politics — has risen. Years ago in Moscow, Ablyazov says his security team discovered a sniper’s nest near his house. When he was in London, the police warned him of a threat to his life. Pro-government figures dismiss such concerns but at least two Kazakh opposition leaders have died in suspicious circumstances.

I found Ablyazov juggling mobile phones and laptops as he waged a social media campaign against Nazarbayev. He had lost weight in prison and was wearing a white T‑shirt and jeans. He gave me his business card. It said simply: “Mukhtar Ablyazov: politician.” I asked if he was afraid. “I’ve been living in this state for 17 years already,” he said, so he felt like “tempered steel”. For now, Ablyazov is hoping to be allowed to remain in France. But he told me, matter-of-factly, that he had set a two-year timetable to remove Nazarbayev from office and install himself as Kazakhstan’s interim leader until a western-style parliamentary democracy is in place.

If Ablyazov holds any aces, they are the secrets he learnt from his years on the inside of the Kazakh elite. His strategy now is to target the Achilles heel of what he sees as Nazarbayev’s kleptocracy — the disparity between the prosperity of rulers and the struggles of the ruled.

“Why does the Kazakh copper worker earn one-sixth of what his Chilean colleague earns? Answer: because Nazarbayev runs the thing. I show his assets, his houses, the cash… and I say, ‘He’s stealing from you.’ And it’s very easy for me to do, because every large industrial enterprise is owned by Nazarbayev. He is extremely vulnerable.”

Two can play that game. Diligence and others remain hot on the trail of Ablyazov’s assets and are feeding what their investigators find into ever more court claims. In June, a Kazakh court convicted Ablyazov in absentia of crimes including organising a criminal group and embezzlement. He was sentenced to 20 years. Nonetheless, some of those who have spent years pursuing Ablyazov express bitter frustration at what they feel is his success in crafting an image of a post-Soviet dissident designed for western media consumption.

Ablyazov and his allies have been battling against the British rulings that have frozen his fortune and confiscated his assets. In July, Interpol’s governing body cancelled the Red Notices against him issued at the behest of the Kazakh, Russian and Ukrainian authorities.

Lawyers in the venerable courts off Chancery Lane privately despair of the tactics that are being employed. Each side’s lawyers accuses the other side’s operatives of hacking emails — some of them nominally protected by legal privilege — then offering them as evidence, professing not to know whence they came.

I have asked a score of investigators, lawyers, experts and influential Kazakhs which Ablyazov they considered to be the real one: the desperado or the dissident. Most answered: both. Ablyazov is a product of a place and a time where there was little distinction between money and power. Any action that involves the former necessarily involves the latter, and vice versa.

Assume for a moment that Ablyazov is right, or at least that he is on the cleaner side of a dirty game and might beat Nazarbayev in a fair election. It is easy to imagine others who have challenged authoritarian regimes finding their task harder — impossible, even — had they faced a transnational freelance “repression machine” of the sort Astana has assembled. It tilts the balance in favour of strongmen with access to state coffers.

And if Ablyazov is, as his many enemies and several respected British judges maintain, an audacious fraudster, then all that the Kazakh-funded lobbying, meddling and smearing has achieved is to bolster the narrative of persecution that let him escape being called to account. The real loser, one Astana businessman observes, is the Kazakh budget, which has poured tens, perhaps hundreds, of millions of dollars into the accounts of western firms.

On my last evening in Astana, I sat in the lobby of a down-at-heel hotel talking to Yevgeny Zhovtis, the veteran human rights campaigner. I asked him what he made of the global industry that has grown up to serve the world’s kleptocrats and their rivals, laundering their money, burnishing their image and fighting their battles. “It’s a question for western societies,” he told me. “What are they doing with their institutions and politicians? Our corrupted elite has not corrupted itself.”

Written by Tom Burgis is the FT’s investigations correspondent

Illustration by Evelin Kasikov, photographed by Benjamin Swanson, with portrait by Vasantha Yogananthan

Photographs: Vasantha Yogananthan; Eva Vermandel; Bloomberg; AFP/Getty Images; Paris Match/Getty Images

Original Article : https://www.ft.com/content/1411b1a0-a310-11e7-9e4f-7f5e6a7c98a2