For more than a decade, one mysterious transportation company has been primarily responsible for moving Kazakhstan’s oil and gas by rail. Its rise was made possible by a strong and lucrative partnership with the country’s largest oil and gas producer. But despite its leading role in the industry, it has continued to fly under the radar. Even as it made millions of dollars in profits, the identity of its owners has remained hidden, disguised by a growing network of offshore companies.

The secrecy was not for nothing. As it turns out, this transportation company, TTG Group, had friends – and shareholders – in high places. For most of its history, and possibly still today, one of its owners has been Sauat Mynbayev, Kazakhstan’s former oil minister and now CEO of KazMunayGaz, the state oil and gas company, according to an investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

The revelation comes from the Paradise Papers, an offshore leak obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which organized the global collaboration of which OCCRP is part.

Built on the foundation of a former state-owned enterprise, TTG Group owns Kazakhstan’s largest private fleet of oil and gas rail cars, maintenance facilities, and a rail depot that services the country’s largest oil field. Its operations are conveniently based in western Kazakhstan, where most of the oil and gas industry is located.

And the group’s success largely depends on one key customer – Tengizchevroil (TCO), a Chevron-led consortium that includes ExxonMobil, LukArco (owned by Russia’s Lukoil), and KazMunayGaz, the very same state oil giant that Mynbayev now heads.

His leadership of the company and his former role as oil minister make Mynbayev responsible for the stewardship of the oil wealth on which much of the country’s economy depends. But at the same time, his private business interests in rail transportation have earned him and his partners at least $260 million.

As a public official, Mynbayev had an obligation to declare this conflict of interest. There is no proof he ever did.

The deal may put the Western companies at odds with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act depending what they knew about the conflict of interest.

But what are the odds that he would ever be found out? TTG Group’s ownership structure is a convoluted maze of offshore holdings. Even those with the patience to follow the trail as far as it goes – and the access to do so – would find no trace of Mynbayev and his partners.

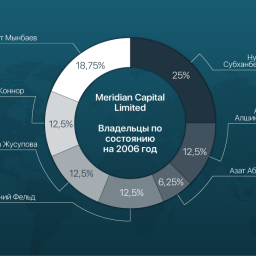

The Paradise Papers leak provided OCCRP reporters with the first clue: Mynbayev’s stake in Meridian Capital, an investment holding company registered in the tax haven of Bermuda. Even so, it took the fortuitous find of a single sentence in a financial report filed this year to connect Meridian to the Kazakhstani transportation conglomerate.

Meridian Capital did not respond to requests for comment, and representatives of KazMunayGaz initially denied that Mynbayev had any relationship with Meridian Capital.

However, after the publication of an earlier OCCRP story linking him to the offshore firm, Mynbayev admitted that he had been its shareholder, but said that he had declared this in his tax documents, and that he had given up his stake “several years ago.”

Contacted by OCCRP again for this story, Mynbaev’s office did not comment, but said that a lawyer would be in touch with reporters. No subsequent communication was received. No other Meridian shareholders responded to requests for comment.

Records from Appleby, the law firm whose documents form much of the Paradise Papers leak, list him as being an “active PEP” – a “politically exposed person” – as recently as April 2016. This means that, as of that date, he was likely still a shareholder of an offshore firm under its management. (See: Kazakhstan’s Secret Billionaires)

Inside the Matryoshka Doll

Kazakhstani business records are incomplete, and those that were found contradict TTG Group’s own claims about its origins, making it impossible to definitively establish its history and its owners. That’s why coming to understand how it came under the control of Meridian Capital – and how that connection helped ensure its success – requires diving into its complex offshore holding structure.

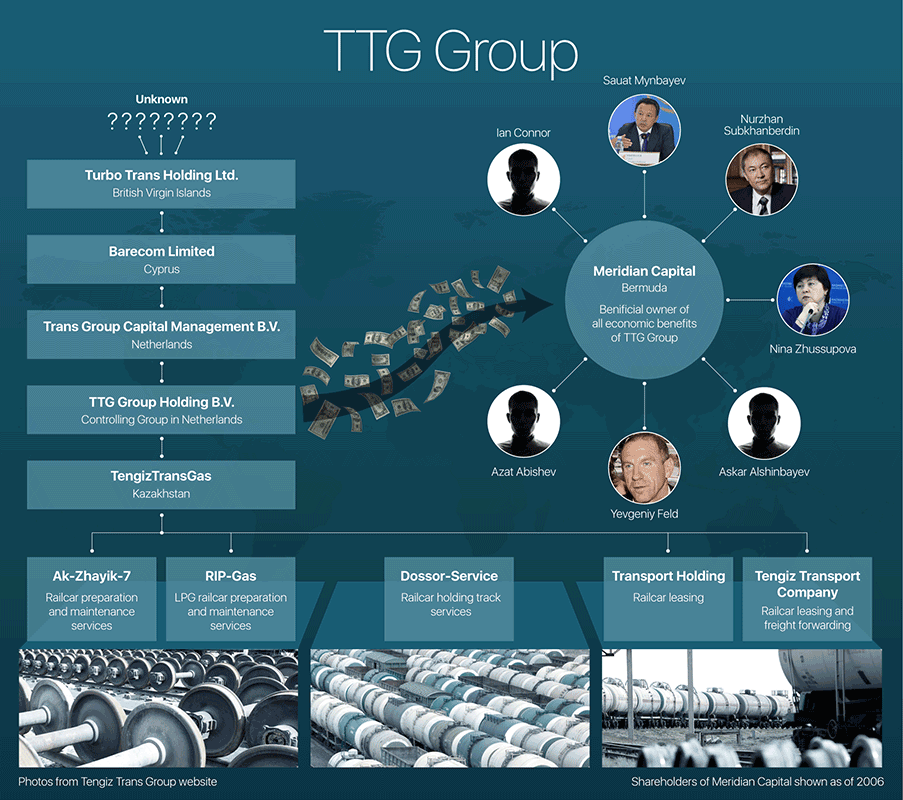

TTG Group is a Dutch holding company that owns TengizTransGaz, the group’s Kazakhstani operational company, and five more subsidiaries. But that’s not all. TTG Group itself is owned by another Dutch company, which in turn is owned by a Cyprus company owned by a BVI company – followed by even more layers of offshores.

None of these layers include Meridian Capital, the company of which Mynbayev is a shareholder.

But a financial report filed this year by TTG Group reveals that on Sept. 16, 2011, an unusual secret deal took place. That deal gave one of Meridian’s companies the option to purchase all of TTG Group’s shares for $1.

Exercising this option would have made Meridian Capital show up within the group’s ownership structure – and run the risk of being disclosed to the public. This never happened – on paper, the structure remained the same.

Since the contract that governs the 2011 deal is not available, the other terms it established are unclear.

But the financial report filed this year reveals that, since that day, “the beneficial ownership” and “all economic benefits” of TTG Group have ultimately belonged to Mynbayev and his partners. This means that the deal must have included some kind of mechanism that enabled Meridian to receive TTG Group’s profits without becoming its formal owner.

By this point, TTG Group had already become massively profitable, with annual revenues of $100 million and profits of over $40 million in 2010 alone. And no wonder – Kazakhstan’s oil industry was in the middle of a massive boom.

The fact that Mynbayev and his partners appear to have received such a profitable company for nothing strongly suggests that the deal they made was with themselves – TTG Group had been theirs all along, and the agreement was a clever way to move money across jurisdictions.

There are other possible explanations for such a deal. For example, it could have been a corporate raid, which would mean that Mynbayev and his partners had taken TTG Group over from somebody else. Or it could have been an inside takeover, suggesting a falling out among partners. But OCCRP reporters were able to obtain additional evidence for the most likely explanation – that Meridian Capital’s founders had controlled TTG Group from the beginning. (A review of the company’s website, including archived older versions, revealed no announcements that it had ever changed hands.)

TTG Group claims to have been established in 2001. At that time, according to his biography, its board chairman was a man named Yevgeniy Feld – a Meridian cofounder and former executive at one of Kazakhstan’s largest banks, Kazkommertsbank. As it turns out, this was the same bank that provided crucial financing for TTG Group in its early days. Several other former Kazkommertsbank executives, including Mynbayev, also became Meridian shareholders.

There is further evidence of continuity in the transportation company’s ownership. TengizTransGaz, the local operational company, was acquired by TTG Group, the Dutch holding company, in 2008, in a transaction that was described as being part of an “intra-group restructuring.” This financial term indicates that the operation did not involve a change of ownership – meaning that whoever owned the company before 2008 also owned it afterwards. Both ends point to Meridian Capital.

If it is indeed true that Meridian Capital controlled TTG Group during this entire decade, this would go a long way towards explaining the company’s stunning success. (And a 2013 loan of $85 million given to Meridian by a local subsidiary of TTG Group, and apparently never repaid, provides further evidence that Meridian continued to profit from its successful Kazakhstani endeavor.)

With access to financing from Kazkommertsbank and the benefit of Mynbaev’s many influential positions – including Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Minister of Oil and Gas, and finally, CEO of KazMunayGaz – the group had everything it needed to use their authority and connections to make the company a star.

Rising Star

The Tengiz field, stretching for miles along the northern shore of the Caspian Sea, has one of the world’s largest reserves of oil and forms the core of Kazakhstan’s energy industry. (The field is Kazakhstan’s biggest, producing over a third of all Kazakhstan’s oil. Kazakhstan has the 12th largest proven reserves in the world).

The field has been operated by Tengizchevroil, the joint American-Russian-Kazakhstani consortium, since 1993. The company uses different oil export routes – but most of the crude goes through a thousand-mile pipeline from the field to Novorossiysk, a Russian port on the Black Sea. The rest is shipped by rail, also to Black Sea ports, from which it is then sold on the world market.

Shipping the oil and gas by rail is a massive and expensive undertaking. Though Tengizchevroil owns the railroad – one of the world’s largest private tracks – it doesn’t own the railcars nor any of the support facilities.

This is where TTG Group comes in.

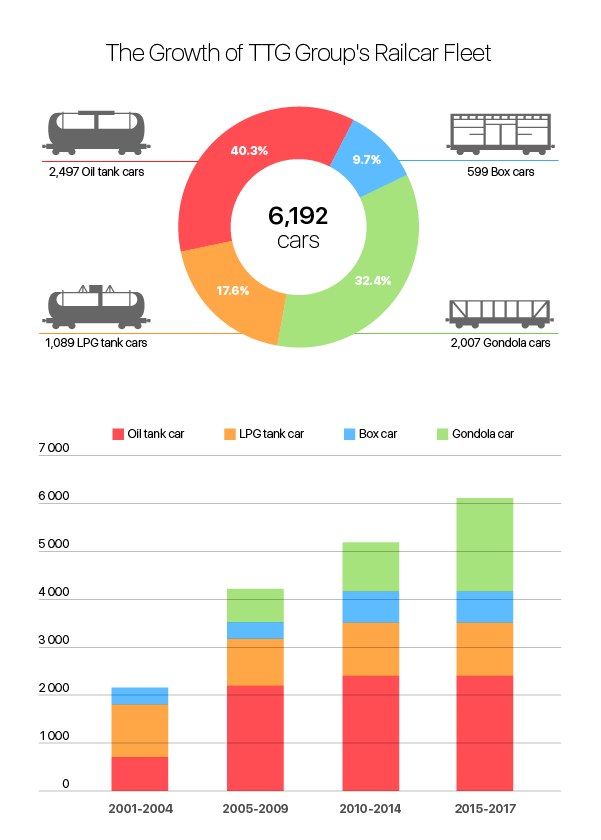

Acquiring rail cars and leasing them to the international oil consortium was the first thing the company did, and for years this was its most lucrative business. After initially buying only oil cars, the company soon diversified into gas, sulphur, and other products carried by Tengizchevroil.

Its first batch of 796 railcars, acquired in 2001, came from Alautransgaz, a regional transportation monopoly which held former state assets.

Mynbayev likely helped too. In 2002, while he was chairman of the Kazakhstan Development Bank, the bank gave TTG Group an $11.7 million loan to purchase another 300 railcars. All of the cars had a guaranteed customer – Tengizchevroil. Over the years, TTG Group continued acquiring more cars and leasing them to their favorite customer. By today, the fleet has grown to over 6,000 cars.

The cars are not the only valuable asset TTG Group scored from Kazakhstan’s former state monopolies. One of its most valuable assets – a facility the group itself describes as the foundation of its business – was RIP-Gaz, Kazakhstan’s only servicer of gas tank railcars, which it also bought from Alautransgaz. Furthermore, Tengizchevroil requires every company that it leases cars from to carry out a pre-inspection at the facility every time they’re filled with gas – more money into TTG Group’s coffers with every shipment.

The group soon made other acquisitions. In 2005, it bought another maintenance company, Ak-Zhayik‑7. The following year, it won a Tengizchevroil tender to build a large railcar parking depot.

Another business opportunity soon presented itself. After years of pressure, the government fined Tengizchevroil $609 million for stockpiling sulphur, a byproduct of oil production, in violation of environmental regulations. This meant that the consortium would have to begin exporting its considerable stocks – and TTG Group was there to help ship it away. The company started buying cars that shipped sulphur, leasing them to Tengizchevroil, and charging for maintenance. Since 2010, TTG Group has transported over 3 million tons.

As of April 2012, TTG Group has also been acting as Tengizchevroil’s freight forwarding agent.

A Loan With No Repayment Schedule

Between 2008 and 2015, Meridian Capital received at least $176 million in dividends out of its arrangement with TTG Group.

But direct profits aren’t the only benefit Meridian sees. One deal OCCRP reporters found provides an example of how they move money to Meridian.

On Sept. 4, 2014, TTG Group took out a loan from its Kazakhstani subsidiary, TengizTransGaz, for $85 million. On the very same day, it lent the exact same amount to Meridian Capital International Fund, a Cayman fund that belongs to Meridian.

It does not appear that either of the companies ever paid the money back. “There is no repayment schedule in place regarding this loan,” reads the financial statement. A genuine loan between independent entities would not have required using an intermediary in this manner. The complex arrangement – as well as the fact that the loan appears never to have been repaid – is another piece of evidence suggesting that Meridian and TTG Group are controlled by the same people, and that Meridian is profiting handsomely from the arrangement.

More Profits In Sight

With an ongoing Tengiz expansion project and the development of new oil fields, along with the prospect that Kazakhstan will increase its production of natural gas, TTG Group’s future (and Meridian’s) seems bright.

But TTG Group is not the only company Meridian controls.

On Feb. 2, 2011, through another Dutch company, Freight International Holding, Meridian gained control of a Kazakhstani company called the Caspian Freight Company for a nominal price of €1,000. Meanwhile, according to the Dutch company’s 2015 financial statement, Caspian Freight Company was worth over 1 billion KZT (€2.7 million). The fact that Meridian acquired it for just €1,000 may indicate that it was theirs all along.

Just as with TTG Group, the name Meridian itself appears nowhere in the ownership structure. And just as with TTG Group, Caspian Freight Company appears to have begun building another Kazakhstani transportation empire. In 2014, it acquired majority stakes in two Kazakhstani transportation companies, Alautransservice (formerly part of Alautransgaz) and Germes Capital Management.

Within the country, there are no public reports, news articles, or web sites that would indicate that these companies all belong to the same secretive group. But given the savvy and aggressive tactics used by Mynbayev and his banker partners, it is likely that there are more lucrative deals in their future.

Legal Questions?

According to experts on the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, Chevron and ExxonMobil’s involvement may violate the act, which bans US companies from making payments to foreign officials in exchange for preferential treatment in business. This would depend on whether the companies knew, or could reasonably have been expected to know, that Mynbayev would personally benefit from their deal with his government – and whether these deals could be construed as benefits provided to him for the purpose of obtaining business.

“Merely claiming ‘we didn’t know about the conflict of interest, we didn’t know that this entity was owned in significant parts by the minister’ is in itself not a defense,” said Andy Spalding, professor at the University of Richmond School of Law in Virginia and senior editor at the FCPA blog. “The analysis is [whether] you have reason to believe that money going through your subsidiary to this company was going to be used to bribe him or anybody else.”

However, Spalding said, for a company to be in violation of the act, “we have to have evidence of something of value given [to TTG] with a corrupt intent.”

It is not known what ExxonMobil or Chevron knew about TTG Group’s ownership or Mynbayev’s involvement.

In response to inquiries for this story, TTG Group declined to comment and ExxonMobil referred reporters to Tengizchevroil and Chevron.

A Chevron spokesperson wrote that the company “abides by a stringent code of business ethics” and “complies with all applicable laws.” Tengizchevroil declined to comment on what it described as a “commercial issue,” citing company policy.

Additional reporting by Aubrey Belford, Olga Gein, Vlad Lavrov, and OCCRP Kazakhstan.

by Miranda Patrucic and Ilya Lozovsky

Top Kazakhstani Official Holds Stake in Secretive Transportation Empire