A French judicial investigation into suspected corruption surrounding the sale to Kazakhstan of satellites made by aerospace giant EADS, now renamed Airbus Group, has discovered the trace of a mysterious payment of 8.8 million euros made by the group to an offshore company whose true owners are unknown, apparently even to Airbus. The investigation also centres on the sale to Kazakhstan by EADS of 45 helicopters, and the deepening scandal implicating Airbus in what has become dubbed “Kazakhgate” is joined by separate probes in France and Britain into the group’s alleged corrupt practices in past sales of its civil aircraft. Martine Orange and Yann Philippin report.

Airbus Chief Executive Thomas Enders and three other high-ranking management figures from the European aerospace group were interviewed by French anti-corruption police last month in connection with the sale to Kazakhstan of satellites and helicopters by the group under its former name EADS.

The sale of the satellites built by Astrium (now Airbus Defence and Space) was the first of a series of contracts with Kazakhstan signed between 2009 and 2011which included the sale of 45 helicopters built by EADS’ France-based division Eurocopter (now Airbus Helicopters), and 295 locomotives built by French engineering firm Alstom, which altogether totalled 2 billion euros.

A judicial investigation into suspected “bribery of foreign public officials” and “money laundering” in the helicopter deal was launched after evidence emerged of secret bungs paid to intermediaries and French officials connected to the sale.

Enders, along with Airbus Chairman Denis Ranque, Airbus Group General Counsel John Harrison and former French minister Noëlle Lenoir, who sits on an independent panel set up earlier this year to advise Airbus on its anti-corruption practices, were questioned as “witnesses” by investigators from the French police anti-corruption and tax fraud office, OCLCIFF, at its headquarters in the Paris suburb of Nanterre.

There is no suggestion that any of the four were involved in the suspected corruption in the deals under investigation. Well-informed sources have told Mediapart that the three magistrates in charge of the judicial investigation in particular wanted to establish the degree of cooperation that Airbus would lend their investigation.

Much is at stake for Airbus in such discussions. The group is separately at the centre of investigations opened in Britain and France since 2016 into fraud and bribery allegations that it paid out secret commissions worth hundreds of millions of euros during sales of its civil aircraft. It has publicly recognised that it risks a heavy “monetary penalty” at the end of the British and French investigations.

The creation earlier this year of the panel of independent monitors of its business practices, on which sits Noëlle Lenoir, a former French minister who has served as a member of leading judicial and administrative bodies, the Conseil d’État and the Constitutional Council, was regarded as strengthening Airbus’s chances of escaping prosecution on eventual corruption charges over its jetliner sales by agreeing to a financial penalty settlement (made possible after a recent change in French law, known as “the Sapin 2 law”).

In that investigation Airbus is dealing directly with the financial crime branch of the French public prosecution services, the PNF. The PNF appears keen to use the settlement process allowed by the Sapin 2 law, as illustrated earlier this month in an out-of-court settlement with the HSBC bank after it agreed to pay 300 million euros after admitting money laundering and helping tax evasion. But in the case of the helicopter and satellite sales to Kazakhstan, Airbus must convince the independent magistrates in charge of the judicial investigation to allow such a deal before then negotiating with the PNF.

The probe into the group’s sales to Kazakhstan, conducted under its former name of EADS, is notably attempting to unravel the circumstances of a mysterious payment of several million euros made by EADS to an offshore account in connection with the satellite deal Mediapart can reveal in this investigation conducted with media partners France Inter radio and German weekly magazine Der Spiegel.

This was first uncovered in February 2016, during a police search of Airbus offices in the Paris suburb of Suresnes. The search found evidence that in 2009 the group had made a payment of 8.8 million euros into a Singapore bank account as part of the satellite deal. The bank account was in the name of a company called Caspian Corp, registered in Hong Kong.

Following the discovery, Airbus provided the judicial investigation with the report of an internal audit the group made in 2015 into its sales campaign with Kazakhstan between 2009 and 2011. Mediapart has had access to the report, marked up as “Strictly confidential” and dated July 15th 2015, which reveals that a total of 9.6 million euros were paid in relation to the satellite deal to “two entities linked to Lyès Ben Chedli” who the report describes as a “business partner” for the group. The payments were made up of 800,000 euros transferred into a Swiss bank account in the name of LBC Consulting, a Tunisian company owned by Ben Chedli, and a further 8.5 million into the shell company Caspian Corp.

The auditors found “several elements” that were irregular in the payments, and notably that the contract with Caspian Corp was signed “without respecting” the group’s procedures. That contract was eventually terminated in April 2013 after the Caspian Corp bank account in Singapore was closed down on the initiative of the bank. The report was concerned over the use of “complex” contract structures involving locations where there was a “high level” of secrecy.

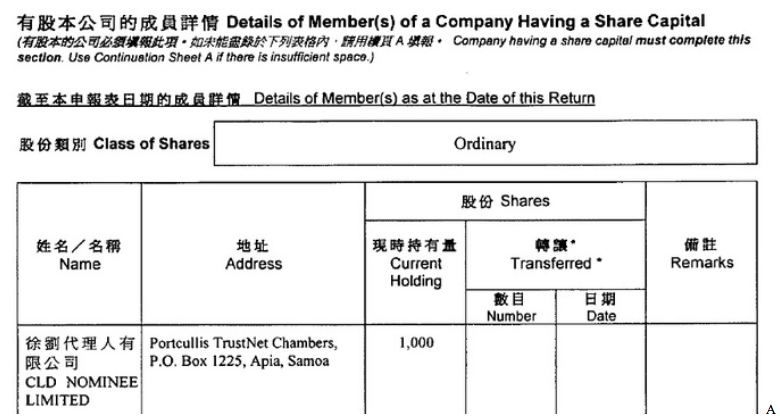

Caspian Corp itself belonged to a shell company managed by frontmen and registered in the Polynesian state of Samoa. The audit report noted that the true beneficiary of the company was unknown and that there was no material evidence that it had provided any services. It recommended that further investigations should be made in the group to establish “a more detailed understanding” of the transactions and eventual connections with those implicated in the judicial investigation in the Kazakh deals.

But the judicial investigation was subsequently informed by Swiss bank Lombard Odier, where Caspian Corp also held other accounts, that the owner of the company was Lyès Ben Chedli. Contacted by Mediapart, Ben Chedli declined to be interviewed, insisting that he had no involvement in the suspected corruption under investigation.

Ben Chedli is a Tunisian business intermediary and consultant, who has notably worked with Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal, and has a wide range of contacts, from Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz to Bashir Saleh, the former paymaster of the regime of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. During the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy, Ben Chedli enjoyed close relations with Sarkozy’s chief of staff and later interior minister, Claude Guéant, who he at the time described as a “friend”, and also Sarkozy’s longstanding ally, businessman Nicolas Bazire.

In 2008 Ben Chedli met for the first time Patokh Chodiev, an Uzbek oligarch and joint owner of the largest mining group in Kazakhstan, where Chodiev enjoys close relations with the country’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev. At the time, Chodiev wanted to establish a contact with the French government and Ben Chedli proposed helping him. It was a timely moment, as Nicolas Sarkozy, elected as French president in 2007, was keen to deepen commercial ties with Kazakhstan, a wealthy Central Asian state.

Ben Chedli introduced Chodiev to Sarkozy’s advisor on Central Asia, Damien Loras, and also to two high-ranking EADS (now Airbus) executives, commercial director Marwan Lahoud and his deputy, Jean-Pierre Talamoni.

Soon after, Ben Chedli signed a preliminary deal, in the name of his Tunisian company LBC Consulting, with the EADS space division Astrium to provide his services for the sale of two of its satellites to Kazakhstan. This consisted of a regular monthly payment of 30,000 euros during the negotiations, plus a payment of 3% of the value of the final deal to be paid into a different entity and which would be designated when the contract was sealed. In all, this represented the payment of 9 million euros.

‘Singapore no longer felt at ease with the account’

Ben Chedli and Chodiev were to meet on several occasions in the Kazakh capital Astana and also Paris. In July 2009, Chodiev hosted a meeting at his villa at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, on the French Riviera, between Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev, Sarkozy’s Central Asia advisor Damien Loras, and the French presidency’s chief diplomatic affairs advisor, Jean-David Levitte. According to a source with close knowledge of the events, Chodiev’s skilful handling of the commercial relations was a decisive factor in the sale of the satellites, and the contract, worth a total of 300 million euro, was eventually signed on October 6th 2009 during a visit by Sarkozy to Astana.

France followed up with further deals with Kazakhstan, the last of which was the sale of 45 helicopters built by EADS subsidiary Eurocopter, but the background to these would soon take a bizarre turn. Chodiev, was under threat of prosecution in Belgium for conspiring with criminals and money laundering in connection with property deals he made in the country, and turned to the French presidency for help in escaping trial on corruption charges in Belgium (see more here).

Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev with then French president Nicolas Sarkozy in Astana on October 6th 2009, the day of the the signing of the contract for two EADS satellites. © Reuters

In exchange for France’s help, he offered his own services in organizing the secret payment to the then Kazakh prime minister Karim Massimov of 12 million euros to help push through the deals with EADS. It is not known whether EADS ever made the secret payment, and the Airbus 2015 internal audit found no trace of it.

The plan also involved a secret 5‑million-euro kickback from the deal which was to be paid to beneficiaries in France, organised by Chodiev and transported to Paris in cash from abroad by car.

Meanwhile, Lyès Ben Chedli was to become ousted from the dealings with Kazakhstan after disagreements reportedly developed with both the Sarkozy administration and also Chodiev.

In April 2010, Airbus signed a contract with Caspian Corp for the pre-agreed bonus payment to Ben Chedli of 3% of the value of the completed satellites deal. The contract was managed by EADS sales and marketing executives Jean-Pierre Talamoni and Olivier Brun. Their Paris-based department, known as the SMO, was wound down by Airbus in 2016 following the emergence of evidence of corrupt practices by the group.

Airbus paid a total of 8.8 million euros to Caspian Corp in several stages. However, in May 2014 the plot suddenly thickened when Ben Chedli brought a case before the Paris commercial court against Airbus alleging that he had never been paid the agreed amount. That suggested that either Chedli was attempting to be paid twice, or that Airbus had paid unknown beneficiaries behind Caspian Corp.

The ongoing judicial investigation into the Kazakh deals questioned Laurent Pictet, the person in charge of the Caspian Corp account with Swiss bank Lombard Odier, based in Geneva, who confirmed that Ben Chedli was the owner of the accounts. “The starting point of the banking relationship is due to the fact that Mr Ben Chedli, via his company Caspian Corp […] signed a contract with EADS,” Pictet said in his statement to the French investigation and seen by Mediapart. “Mr Ben Chedli had a contract as a business contributor which stipulated that he was paid 3% of the sale [price] of the satellites to Kazakhstan […] The economic beneficiary of Caspian was Mr. Ben Chedli. It seems to me also that he was the unique shareholder.”

In March 2009, during the initial manoeuvring for the deals with Kazakhstan, Ben Chedli in fact created three offshore companies. One was Caspian Corp which was registered in Hong Kong through the services of Portuguese law firm Mazars. Another was Talyo Technologies which was registered in Panama, and the third was Eurasian Technologies registered in the Seychelles, both of which were set up with the legal help of Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca.

Ben Chedli opened bank accounts for the three companies in Switzerland, and also for his Tunisian company LBC Consulting. He also subsequently requested that Lombard Odier open a second account for Caspian Corp at its subsidiary in Singapore. “That is because Mr Ben Chedli told us that EADS had refused to pay the commission into a Swiss account,” Pictet told the French investigation, adding that he had corresponded with the person in charge of payments to intermediaries for the SMO department, Olivier Brun, “to confirm the existence of the contract and more particularly about the money payments”.

In his statement, Pictet described his bank’s relationship with Ben Chedli as “four years of disaster”, and said that the Tunisian emptied the account which had been opened originally by the bank on the understanding it was to be managed as a wealth investment account. “On several occasions we gave him warnings by email or letter indicating that we no longer agreed to carry out payments traffic. It involved paying private jets, cars, jewellery and to pay the monthly bills on his credit card, which involved crazy sums.”

Pictet said that because “Mr Ben Chedli never respected anything” the bank’s Geneva office ran into problems with its representatives in Singapore. “We never stopped sending him warnings, up until the day there was nothing left,” he said. “We were watching it very closely because we didn’t want to pay retro-commissions [secret payments made from other secret payments]. So we monitored the payees […] Most of the payments were made by credit card.”

“Given what Mr Ben Chedli was doing, Singapore contacted me to say they no longer felt at ease with the account and they proceeded to close the account, notifying the client by letter.”

Among the questions raised by the banker’s testimony is whether Caspian Corp could have been set up to serve Airbus in order for it to discreetly remunerate other people connected to the trade deals in Kazakhstan.

Meanwhile, Lyès Ben Chedli lost his case brought against Airbus at the Paris commercial court. He did not subsequently make use of a clause in the contract signed with EADS (renamed Airbus Group) which allowed for an arbitration procedure.

Contacted by Mediapart, neither Airbus nor Lyès Ben Chedli accepted to be interviewed about the events reported here. In response to our request for an interview, Lyès Ben Chedli wrote to Mediapart by email: “I quite simply do not wish to make any statement in a so-called ‘Kazakhgate’ affair which does not concern me, neither near nor far.” He insisted that he had no involvement in “acts of corruption that the ones and the others are accused of”, and warned that he would take legal action if “false or erroneous” information about him was published.

BY MARTINE ORANGE AND YANN PHILIPPIN