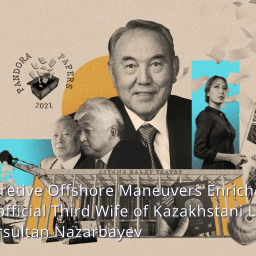

Long synonymous with Sherlock Holmes, the building at 221B Baker Street in London now represents a tragic irony: The fictional crime-fighter’s address has been linked to the kleptocratic regime of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the de facto authoritarian ruler of Kazakhstan from 1990 until recently. His first daughter, Dariga, has been reported as owning this property and a significant number of other London residences. (Dariga Nazarbayeva, through an attorney, declined to comment when asked about this.)

While London has long looked the other way at these kinds of investments, the political landscape in Britain has dramatically shifted following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Now that the British public and government have become more aware of the scale of offshoring from post-Soviet countries, there is a strong chance to extend some of the regulatory reforms directed towards Russian oligarchs to also apply to the Nazarbayev family.

Nazarbayev’s family and his patronage network have an extensively reported history of offshoring wealth, especially into Britain, which permitted this practice. According to a December 2021 report by Chatham House on post-Soviet kleptocracies and their offshoring methods in Britain, the authoritarian’s family alone already owns at least $446 million worth of property there—and that could be “the tip of a very large iceberg,” researchers say, since so much property was acquired through offshore companies.

Now, though, as Nazarbayev loyalists are chased out of Kazakhstan amid an apparent purge by the newly consolidated regime of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, a flood of kleptocratic wealth may start surging into British and other offshore accounts very soon, if it hasn’t already. Britain remains unaware of, and unprepared for, this development—but its outsized presence in the Nazarbayev regime’s offshoring networks means it has the power to preempt these financial flows, as well as the opportunity to lead the transatlantic community in crafting a proactive and broad response.

A furtive flow

While Britain has taken some steps to curb Russian offshoring since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, including promises to create a kleptocracy cell in the National Crime Agency, little equivalent action has been taken against other sources of offshoring, including Kazakhstan. Notably, investment funds and similar private corporate vehicles have played an increasingly prominent role in offshoring efforts from Kazakhstan.

For instance, with the help of these corporate vehicles, Nazarbayev’s youngest daughter, Aliya Nazarbayeva, is reported to have moved $300 million out of Kazakhstan in 2006 through a spending spree in London, which included a private jet and a $12.5 million mansion.

According to the Chatham House report, much of the UK-based property owned by Nazarbayev’s family and close associates was acquired through firms based in the British Virgin Islands (although at least one was based in Luxembourg and another in Liechtenstein). All of these jurisdictions have long attracted attention for their lack of transparency and compliance with anti-money-laundering measures. The scale of the incoming offshoring surge will likely be in the billions of dollars: Nazarbayev alone reportedly controls at least $7.8 billion concentrated in charitable organizations based in Kazakhstan. While Nazarbayev himself does not officially own these foundations, under Kazakhstani law he has ultimate control over their assets because he founded them.

The only current barrier to this oncoming wave is a 2010 Kazakhstani law that granted Nazarbayev the title “Leader of the Nation” and provided him legal immunity from prosecution for any actions committed while he was in office. It also prevents the state from seizing property owned by him and his family, and allows them to keep their banking documents secret.

However, Tokayev has already started purging Nazarbayev’s old patronage network and announced the establishment of a public fund to which he demanded that Nazarbayev-era businessmen contribute. He has also begun directly restricting the financial activities of the Nazarbayev family—such as by ending a government contract with a waste-management company linked to Aliya Nazarbayeva. The company, Operator ROP, which once enjoyed a monopoly in Kazakhstan, was further hit when the company’s chairman was arrested. Nazarbayev’s nephew was also arrested recently, and it’s likely that Kazakhstan’s rubber-stamp parliament will revoke the 2010 law to pave the way to directly seizing Nazarbayev family wealth.

Cracking down on dirty cash

But Tokayev’s purge of the former Nazarbayev regime has not yet intensified—giving transatlantic authorities, particularly those in the United Kingdom, critical time to prepare for the influx of cash. This is especially crucial now that there is momentum for cracking down on offshoring in Britain following the new sanctions actions taken against Russian oligarchs. Even shortly before the invasion, Member of Parliament Margaret Hodge suggested that the UK Parliament is considering placing sanctions on Kazakhstani billionaires in Nazarbayev’s inner circle.

First, British law enforcement agencies should execute the new powers afforded to them under the new economic crime bill just passed by Parliament, but this can only happen if they have more resources. Anti-corruption measures in Britain have consistently been under-enforced despite having robust legislation because law enforcement is “under-resourced, over-stretched, and out-gunned,” according to the nonprofit Spotlight on Corruption.

Secondly, the British government needs to follow up on its commitment to pass another economic crime bill. A second bill needs to address the usage of Unexplained Wealth Orders (UWOs), which empower authorities to seize the assets of a person believed to have criminal connections if the person cannot prove those assets were acquired legitimately. Although the first bill already expanded the potential scope of UWOs to cover potential associates of people with unexplained wealth, other changes are necessary. British think tank RUSI identified expertise, inter-agency cooperation, resources, and political will as essential for UWOs to be most effective, and a follow-up bill must account for this.

As Kazakhstani kleptocrats demonstrated by reportedly fleeing the country in their private jets amid January’s widespread protests, the lax financial regulations that benefitted Russian oligarchs and helped build Vladimir Putin’s war chest can be exploited by others. Therefore, there is a real security threat to continuing to turn a blind eye to the threat of transnational corruption.

Given Britain’s status as the offshore haven on which the former Nazarbayev regime has relied, it should take advantage of the current anti-corruption political momentum to both reverse this trend and lead by example in dealing with this illicit patronage network. It is not too late for British officials to ensure accountability and warn any others considering laundering their ill-gotten gains that their money is no good here.

Francis Shin is a research assistant in the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center focusing on anti-money laundering and countering kleptocracy. Previously he was a research assistant at the Future of Financial Intelligence Sharing program, a research partnership with the Royal United Services Institute’s Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies.

Original source of article: www.atlanticcouncil.org