Alisher Usmanov, who has been closely tied to top Russian leaders, hides behind trusts, secretive offshore companies, Swiss bank accounts, and his family members to detach his name from his billions.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov — one of the world’s 100 wealthiest people — has been sanctioned by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union.

As a particularly well-connected figure, Usmanov is an obvious target. He has been accused of being close to President Putin, providing luxurious homes to former Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, and otherwise supporting Russia’s ruling regime. As the owner of the business daily Kommersant, he fired an editor and a top manager who oversaw its reporting on election violations committed by the ruling United Russia party.

Western sanctions against Russian oligarchs are meant to deny them the enjoyment of their wealth and, in effect, to punish them for their support of the Putin regime. But as the world is rapidly discovering, it’s not so simple to sanction an oligarch.

Usmanov’s $19-million Sardinian villa may have been seized by the Italian government. But German authorities appear to have struggled to formally impound his infamous $600 million yacht, the Dilbar, which is moored in Hamburg.

“The yacht is registered in the Cayman Islands and owned through Klaret Continental Leasing, a company based in Malta,” Forbes reported, “making it difficult to tie directly to Usmanov for the purpose of sanctions.”

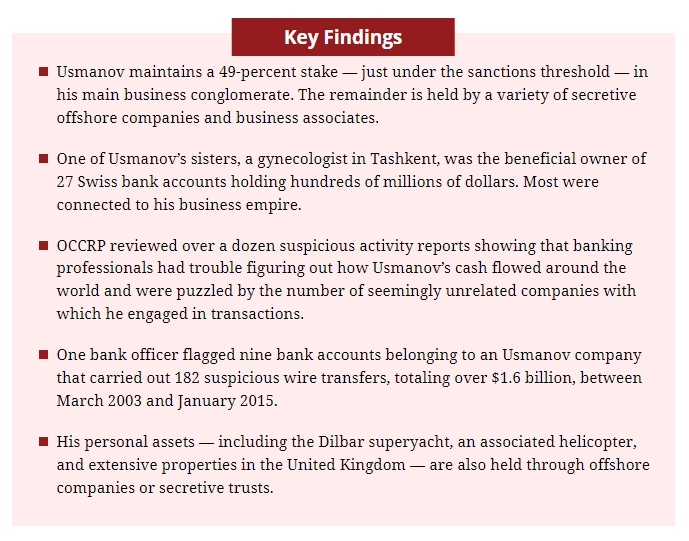

On paper, Usmanov holds only a 49-percent stake in his main business conglomerate, making it a difficult target because the U.S. Treasury uses a 50-percent threshold when imposing sanctions. (He has described this arrangement as a “coincidence.”)

And he has billions in assets that will be even harder to trace. The Uzbek-born businessman has spent years shuffling money around the world among various relatives, shell companies, and trusts.

Given Usmanov’s skill in exploiting the global financial system and its built-in loopholes, it’s unclear whether even identifying all of his assets is possible, much less sanctioning them.

Using information from several large leaks of financial documents and data, including Suisse Secrets, the Panama Papers, and FinCEN Files, reporters from OCCRP and the Guardian have pieced together a partial picture of how Usmanov has hidden his assets in secretive havens like Cyprus, Bermuda, and the British Virgin Islands — and how his money continued to flow through offshore entities for years, even as government officials made inquiries and banking institutions raised red flags about its hidden origins and signs of possible money laundering.

Though some of the data dates as far back as 2004, at least some of the shell companies Usmanov used were operational as recently as 2021.

In response to questions sent by reporters, an Usmanov representative denied that “Mr. Usmanov has ever distributed his wealth among his relatives in order to conceal it from any governments” and said that this allegation is “baseless and unsubstantiated.”

In an earlier communication, however, Usmanov’s press service wrote that his U.K. real estate and his enormous yacht were a “long time ago transferred into irrevocable trusts” whose beneficial rights now belong to his family.

“All of Mr. Usmanov’s businesses have been audited by Big 4 [audit] companies, since their inception, as well as were his personal tax returns and expenses,” his press service wrote. “All of his investments, his expenses and his income have gone through strict compliance procedures.”

The Origins of Usmanov’s Billions

Unlike the fortunes of many other Russian oligarchs, there is no evidence that Usmanov’s billions have their origins in shady post-Soviet privatization schemes. But there is no question that he has benefitted from close government ties, especially with state gas giant Gazprom.

After first becoming wealthy selling plastic bags in the last years of the Soviet Union, he grew his assets into the billions of dollars on the back of a variety of businesses and investments in the subsequent decades.

While often described as an oligarch, Usmanov tries to distance himself from the term, which implies dubious financial gain.

“All the assets my partners and I bought in Russia were from the secondary market, not in any so-called privatization processes,” he told the Financial Times in 2020. “No one ever gifted anything to me.”

Usmanov’s business success in the 1990s led the state-owned gas monopoly Gazprom to appoint him head of its investment arm. In that role, he directed the company to purchase stakes in Russian steel enterprises, critical for producing pipes for transporting gas.

Later, when Gazprom deemed these assets “noncore,” Usmanov and his business partners purchased them from his employer — a conflict of interest that the tycoon did not deny in his Financial Times interview.

In 2017, Russian anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny accused Usmanov of having de facto privatized Russian steel enterprises with the help of an offshore company. Several months later, citing documents from the Paradise Papers leak, which contained material from offshore corporate service providers, Navalny alleged that Usmanov had loaned money from Gazprom’s investment arm — where he still served as general director — to an intermediary offshore company run by his partner in order to make a large investment in Facebook.

At one point, Usmanov claimed to own 8 percent of the social networking company’s shares. Usmanov has also invested in Russian internet services and in the mobile phone provider MegaFon, partnered with Chinese tech firm Alibaba, and reportedly purchased a $100 million stake in Apple.

The World’s Wealthiest Gynecologist?

Saodat Narzieva is a 56-year-old obstetrician and gynecologist who lives in Uzbekistan.

She has practiced medicine for over thirty years, presumably earning a comfortable income as the deputy chief doctor of Maternity Hospital Number 6 in Tashkent.

Even so, her lifestyle is unusually chic for an Uzbekistani doctor.

Her Facebook photos show that she has traveled to Venice, Sardinia, and Dubai, flying on a private jet, enjoying a VIP airline lounge, and cruising on a yacht.

She has also vacationed on the Costa Smeralda, a stretch of land along the northeast coast of Sardinia known for its excellent beaches and turquoise waters.

And if that weren’t enough, leaked data from Credit Suisse shows that Narzieva is listed as the beneficial owner of 27 Swiss bank accounts through which billions of dollars have passed over the years. At its maximum balance in April 2011, just one of these accounts held over $2.1 billion. Many of the others also had maximum balances in the hundreds of millions.

Obviously, Narzieva is no ordinary gynecologist.

In fact, she is the sister of Alisher Usmanov.

Her lifestyle is an example of the kind of luxury accessible to oligarchs’ relatives. But her riches — and those Swiss bank accounts in particular — are also evidence of how even highly-respected Western banks can help obscure the connections between oligarchs and their money.

It’s not clear why Narzieva would be listed as a beneficial owner of these accounts. The data shows that they are corporate accounts — and sixteen of them list contact information associated with USM Group, the massive holding structure her brother uses to unite his business interests.

The leaked Credit Suisse data does not name the specific legal entities that own the accounts. But one of Narzieva’s account numbers matches an account number found in the FinCEN Files, a leak containing reports about suspicious financial transactions. This allowed reporters to identify the entity as Gallagher Holdings, one of the main holding companies Usmanov used to control his fortune.

Since Usmanov is known to have been the beneficial owner of Gallagher Holdings, the Credit Suisse records listing his sister as the beneficial owner of its bank account raises questions.

Moreover, ten of the Credit Suisse accounts were opened in 2013, a period when Usmanov was restructuring his business empire and opening companies for Narzieva, his other sister Gulbakhor Ismailova, her husband, and two business associates.

“This is a strange story,” wrote Graham Barrow, a specialist on financial crime, after reporters conveyed these findings.

“From my experience, it is quite unusual for so close a family member to be used as a proxy,” he wrote. “It is hard to tell why they should have done so in this case, but maybe the fact of the sister not being well known, and potentially a close and supportive relationship between the bank and Usmanov, led to a failure of robust due diligence.”

Enhanced Due Diligence

Barrow further explained how Credit Suisse should have treated Usmanov’s accounts, and why the arrangement uncovered by reporters raises questions.

“Because Alisher Usmanov would need to be dealt with as a PEP [Politically Exposed Person] (and therefore a high risk client), the bank is also required to treat his relatives and close associates in the same way,” he said.

“This means performing enhanced due diligence, which includes (amongst other things) obtaining and confirming the client’s source of wealth as well as verifying the beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles. If [his sister] is listed as [beneficial owner], then it ought to follow that she was the beneficial owner of the underlying entities. If not, then it would require some work to explain why her name appears on the paperwork and not her brother’s.”

“[I]f the sister truly was the [ultimate beneficial owner], this raises all sorts of questions. Was the sister’s lifestyle, as beneficial owner of these companies with huge transactions, commensurate with that financial activity. If not, was it likely she was being used as a proxy for Alisher in which case, they should have responded accordingly.”

“Where it was clear that the beneficial owner was different from the one on their records, it strongly suggests that robust [enhanced due diligence] had not taken place.”

“This is, of course, entirely supposition and the true answer may never be known.”

Usmanov’s press service simply denied the findings: “We categorically deny that Ms Saodat Narzieva had any possession or control of any accounts in Swiss banks on behalf of her brother, Mr Alisher Usmanov, nor did she have any signatory control over any accounts related to Mr Usmanov,” he wrote.

In a statement emailed to reporters, a representative of Credit Suisse said that the bank “cannot comment on potential client relationships,” noted that it “applies all sanctions, in particular those issued by the EU, the United States and by Switzerland,” and rejected “allegations and insinuations about the bank’s purported business practices.”

Suspicious Activities

Though 27 Swiss bank accounts may sound like a lot, they represent just a fraction of the Usmanov-associated accounts held at Credit Suisse and other banking institutions around the world.

The FiNCEN Files leak — which consists of over 2,100 Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) submitted to the U.S. Treasury Department by banks and other financial players — show that Usmanov and his companies held dozens more accounts at Credit Suisse, and at other banks in Cyprus, Russia, and Latvia.

While some of these were Usmanov’s personal accounts or belonged to his real Russian businesses, many others were held by his offshore holding companies or shell companies that appeared to have no clear business purpose and were registered in secretive jurisdictions like Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands.

What’s interesting about the FinCEN Files data is not just the existence of so many bank accounts, but how Usmanov used them to obscure his wealth.

Even banking professionals had trouble figuring out how and why Usmanov’s cash flowed around the world, puzzled by the sheer number of seemingly unrelated companies with which he engaged in transactions.

The SARs show how bank officers repeatedly flagged suspicious transactions totalling billions of dollars, many of which had no clear business purpose, exhibited signs of possible money laundering, had no clear origin, or raised other suspicions.

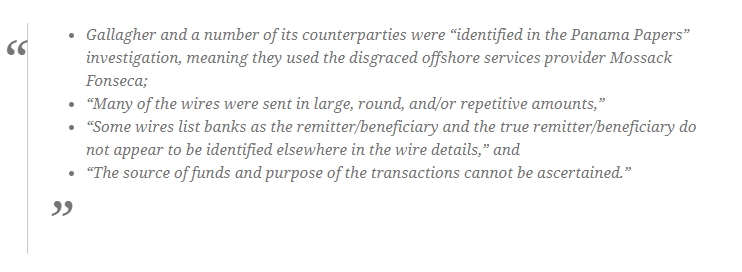

For example, a bank officer with BNY Mellon, a lender headquartered in New York that acted as a correspondent bank for Usmanov’s Gallagher Holdings, identified nine bank accounts belonging to the company that carried out 182 suspicious wire transfers, totaling over $1.6 billion, between March 2003 and January 2015.

In a report submitted to the U.S. Treasury on December 23, 2016, the officer wrote that “the wires are primarily suspicious because Gallagher … appears to be a shell entity, incorporated in Cyprus and banking in Cyprus, Russia, and Switzerland, that conducts a significant amount of wires with numerous other shell entities.”

As further reasons for suspicion, the officer noted a number of other points:

As one example of an especially suspicious transaction, the officer described a $49.5 million wire transfer Gallagher received in April 2004.

The money came from a Bahamas-based “corporate lender” called Sevenkey Limited — whose owner, the officer wrote, “was a trust for the benefit of Igor Shuvalov, a former top aide to [Russian President Vladimir] Putin.”

Gallagher then used the $49.5 million to acquire a stake in a British steelmaker called Corus Group.

“BNYM … is concerned that the funds ultimately came from an individual with such close ties to Putin,” the officer wrote.

The Shuvalov Windfall

The BNY Mellon employee’s suspicions appear to have been well-placed. As reported by Barron’s in a detailed 2011 investigation and then confirmed by the Financial Times, the loan to Usmanov’s company resulted in a large financial windfall for Shuvalov.

Having loaned Usmanov’s company the $49.5 million, initially at a 5 percent interest rate, Shuvalov’s Sevenkey ended up earning back $119 million a few years later after an amendment to the loan terms. This represented a 40 percent annualized rate of return.

As noted by Barron’s, Gallagher’s draft financial reports showed that the company “was able to borrow from banks at a rate of about 9 percent during that period. That invites the question of why it borrowed from Sevenkey [at such a high rate].”

Having been named Russia’s First Deputy Prime Minister, Barron’s also noted, Shuvalov approved the government’s backing of nearly $1 billion in loans to a company controlled by Usmanov.

This was not Shuvalov’s only business arrangement that appeared to involve a conflict of interest. In 2004, Sevenkey bought an $18 million share in the state gas giant, Gazprom, just before the Russian government relaxed its investment rules to allow foreigners to invest in the company. The reform led to a surge in its stock price, earning Sevenkeys more than $100 million on its purchase by 2008.

In response to inquiries from both Barron’s and the Financial Times, Shuvalov denied any wrongdoing.

By the 2010s, Shuvalov was known as one of Russia’s wealthiest public servants. In 2016, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny published an investigation showing that Shuvalov used a private jet worth over $50 million to transport his wife’s corgis to dog shows across Europe.

While these transactions involved external senders and recipients, a separate report filed by Deutsche Bank in July 2017 shows that Usmanov also moved money around within his own business empire in ways that raised suspicions.

Deutsche Bank reported six transfers, totaling over $190 million, that Usmanov sent to himself over a period of three months in 2017. The transactions moved “through multiple personal accounts and accounts for offshore entities that [Usmanov] controls … with no apparent economic purpose,” the report reads.

“Although the transaction details indicate that the payments … were for ‘TRANSFER OF OWN FUNDS’ and ‘DIVIDEND RESOLUTION,’” Deutsche Bank wrote that it was “unable to confirm the commercial purpose of any of these transactions through independent research.”

In another report from February 2017, Deutsche Bank showed how Usmanov sent money to his sister, Narzieva, in a way that raised questions about his true intent. The bank officer listed two wires, totaling over $667,000, he had sent to her the previous year under the description“family funds transfer.”

“This appears to be an unusually large sum of money exchanged to a family member,” the bank officer wrote.

A May 2017 report filed by JP Morgan Chase Bank highlighted a 2012 transfer of $3 million to Narzieva marked simply: “gift.”

Five months later, she sent $100,000 back to her brother in two transfers. The payment details stated that the funds had been sent “to the brother for current expenses” — an amusing claim, considering that Narzieva’s brother is a world-famous multi-billionaire.

Another report, this one filed by Standard Chartered Bank in October 2017, shows what Narzieva appears to have done with most of the $3 million her brother sent her.

“After receiving the $3M gift,” the bank officer wrote,” she “remitted funds totaling over $2.5M to [Shokhrukh] NASIRKHODJAEV,” who has been “identified as the director of a steel company in the UAE.”

“The purpose of the wire transfers between NARZIEVA and counterparty NASIRKHODJAEV … could not be established,” Standard Chartered Bank wrote, “as they appear to be engaged in different lines of business as a doctor and managing director of a steel company, respectively.”

What the report does not mention, but OCCRP confirmed through comments that appear in her Facebook account, is that Nasirkhodjaev is Narzieva’s son-in-law.

Trusts and Secrets

Usmanov’s more concrete assets — shares in his business empire, real estate, and a megayacht — are hidden away in trusts or owned by offshore companies whose precise ownership, and connection to him, is difficult to establish.

In 2018, after Russia faced a new round of U.S. sanctions, Usmanov reorganized his corporate structures, putting 49 percent of USM’s core assets under his own immediate control through Russia. The remaining 51 percent are still scattered across multiple business associates and offshore companies across the world, making it impossible to sanction under current rules.

Thanks to Usmanov’s profligate use of secretive offshore companies, the personal assets he and his family members have acquired over the years are also hard to firmly link to him.

Although the $600-million “Dilbar” superyacht is widely known to belong to Usmanov, the ownership of an Airbus H175 helicopter that sits on the yacht was transferred in 2018 to a Cayman Islands company that cannot be traced to him.

The helicopter can be definitively linked to Usmanov after that date only because it has been photographed physically present on the yacht.

The yacht itself, Usmanov’s press service wrote reporters, has been transferred into an “irrevocable trust” that he does not own and whose beneficial rights had been “donated” to his family.

Also belonging to a trust, his representative wrote, is real estate held by Usmanov in the United Kingdom. The best-known of his properties is Sutton Place, a 16th-century Tudor manor house in the English county of Surrey.

The property, worth at least $40 million when it was listed for sale in the 1990s, is so famously tied to Usmanov that even its Wikipedia page lists him as its owner. But the two Cyprus companies that hold it are themselves owned by a trust services firm that cannot be linked to Usmanov through paperwork. The Financial Times devoted an entire investigation to the question of whether Usmanov “really owns” Sutton Place, and was unable to arrive at an answer.

Finally, as part of OCCRP’s Russian Asset Tracker project, reporters identified six coastal villas connected to Usmanov on the Italian island of Sardinia.

He owns just one of them directly. Two more are owned by his sister Gulbakhor Ismailova. The rest are held through complex corporate structures that lead to a company incorporated in Bermuda.

The trail would have gone cold there — if not for a billing spreadsheet tying the company to Usmanov that was unearthed in a set of leaked records from an offshore services provider.

These are the lengths it takes to connect one of Russia’s most infamous billionaires to his own possessions.

Original source of article: https://www.occrp.org/en/