On February 24, Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine will enter its third grueling year, with no sign of ending.

Countries around the world have imposed sanctions intended to cripple Russia’s ability to wage war, but the flow of high-tech foreign goods into the country continues.

A new investigation by Buro Media, Verstka, and OCCRP exposes one of the ways this is accomplished — a scheme known as “false transit” that takes advantage of lighter or non-existent sanctions against two of Russia’s closest economic partners, Kazakhstan and Belarus.

Both countries are members of the Eurasian Economic Union, a Russian-led trade bloc that integrates the economies of five former Soviet republics , allowing goods to flow freely across national borders with no customs checks.

As reported in previous investigations by OCCRP and Buro Media, sanctioned goods are known to flow to Russia through each of these countries. But the scheme revealed in this investigation makes use of a major loophole that involves both at once.

In this case, a Kazakh company ordered high-tech semiconductor production equipment and other goods from Europe and had them delivered to a temporary Belarusian storage facility. A letter obtained by reporters shows the Kazakh company issuing orders to the storage facility to change the destination of some shipments to Russia, avoiding having to route them through Central Asia.

In total, Russian customs data shows, the scheme appeared to supply nearly $5.9 million worth of sanctioned high-tech goods to a group of Russian companies with extensive military contracts.

Experts say the scheme underscores the key role Belarus continues to play in supplying Russia’s war machine, with the discrepancy in sanctions between the countries creating what one called “a severe hole in the sanctions net.”

Today the Belarus gap is large enough for an armada of trucks, cars and other goods to pass from the West into Russia, and potentially onwards to the battlefields in Ukraine.

– Aage Borchgrevink, senior adviser to the Norwegian Helsinki Committee

“Many of the key war-relevant goods pass through Belarus, which is the key passway of European sanctioned goods besides that via Turkey,” said Erlend Björtvedt, founder and CEO of Corisk, a Norwegian risk advisory firm.

“The role of Belarus is totally different from those of Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan,” he explained. “Belarus is a main physical gateway. The sanctioned goods … are routed from Northern Europe via Belarus to central Russia.”

“Countries in Central Asia take a different role,” he continued. “Their trading companies act as middlemen in the trade but the sanctioned goods are not actually routed physically via those countries.”

Based on trade data from Lithuania, Poland, and Germany in 2022 and 2023, Corisk estimates that about 10 billion euros’ worth of goods ended up in Russia via Belarus — either exported directly to Belarus and then resold, or simply shipped through the country.

“It’s fairly obvious that, in order to make the export controls effective, the Belarus sanctions must mirror the Russia sanctions,” said Aage Borchgrevink, senior adviser to the Norwegian Helsinki Committee.

“Today the Belarus gap is large enough for an armada of trucks, cars and other goods to pass from the West into Russia, and potentially onwards to the battlefields in Ukraine,” he said. “Harmonization of the sanction regimes is also logical, in our view, as Belarus from the start has been Russia’s most important and dependable ally: the platform from where the main attack against Kyiv was launched in 2022.”

A Key Supplier

Russia’s military is supported by a vast array of private companies. Among these is the Ostec Group, a conglomerate that supports high-tech industrial production. Ostec does not produce weapons itself, instead providing the equipment and setting up facilities other contractors need to multiply the military’s arsenal.

Its clients include several major Russian military contractors. Ostec provided foreign-made technologies and technical services to the developer and producer of the Tochka-U and Iskander-M missile systems. The conglomerate is also a supplier and contractor of the Ryazan Radio Plant, owned by Rostec, a major defense conglomerate and one of the largest suppliers of radio communications equipment to the Russian military-industrial complex.

It has also won tenders from the Moscow-based Central Scientific Research Institute of Chemistry and Mechanics, which produces aerial bombs being dropped in Ukraine and was sanctioned in 2020 by the U.S. for developing technology that enabled a major malware attack.

Leaked Russian customs data shows that, before the full-scale war began in February 2022, Ostec was able to import products manufactured all over the world. It sourced many of them from suppliers across Europe, including Portugal, Slovenia, Belgium, and especially Germany.

Immediately after the invasion, many international companies cut their ties with Russia voluntarily, before any sanctions were imposed. Within weeks, all of Ostec’s European partners ceased their shipments to the company — except one.

This supplier, key for Ostec even before the war, was a company called Inter-Trans LLC.

Though located in the Polish city of Siedlce and controlled by a German logistics firm called BMA Spedition GmbH , Inter-Trans was majority-owned by a Belarusian businessman named Evgueni Kostiouk.

Over the course of 2022, Inter-Trans supplied Ostec with at least $24 million in goods — or about half of Ostec’s total imports for the year, as reflected in the leaked customs data. This appears to include all of the goods delivered to Ostec from Europe following the invasion, including solvents and paint thinners, centrifuges for product testing, and optical devices.

Among the shipments was over $4.7 million worth of semiconductor and microchip production equipment.

In February 2023, a full year after the invasion, European sanctions were finally imposed on these items, and Inter-Trans’ deliveries to Ostec dried up as well.

A person answering the telephone number of BMA Spedition, which owns Inter-Trans, said the company had done nothing wrong. “One of the suppliers was set [on the sanctions list],” said the man, who introduced himself at different times as both a manager and an ex-manager. “We were also because we were in the supply chain as a transport company. That’s all.”

‘Send it to Ostec’

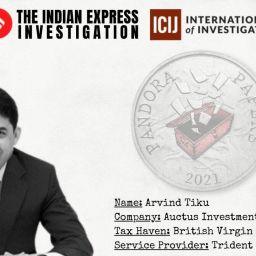

By the time European sanctions were imposed, an alternate route for Ostec had already been set up, based in Kazakhstan but with ties to Kostiouk, the Belarusian businessman behind Inter-Trans.

The Kazakhstan connection appears to date back to 2014, when a Russian firm owned by Kostiouk , Mirtrans, established a daughter company in Kazakhstan, KBR-Trans LLP.

In May 2022, three months after the war started, the longtime director of KBR-Trans, Zhanat Ibraev, co-founded a new Kazakh firm with the same prefix, KBR-Technologies LLP, which quickly started making shipments to Ostec of the same kinds of high-tech goods previously supplied by Inter-Trans.

Among them were six shipments of semiconductor production equipment, largely made in South Korea, that became the first example journalists could find of the Kazakh company sending goods through Belarus.

A letter of instruction obtained by journalists shows how it appears to have worked. In the letter, the director of KBR-Technologies informs the shipping company that the recipient of three shipments, apparently from that July , had changed. The new recipient would be Tefida, a company based in Belarus.

The letter also specifies what would happen next: “KBR Technologies LLP authorizes the private enterprise Tefida to possess the cargo on the territory of the Republic of Belarus and place it under the customs procedure of a customs warehouse, and send it to Ostec Integra LLC of the Russian Federation.”

The letter does not explicitly indicate what the three shipments contained. But customs data confirms that the six shipments of semiconductor production equipment ordered by KBR-Technologies that summer did indeed arrive in Russia in August 2022 — shipped from Tefida.

This equipment was only worth around $716,000, but the following year the same supply route would grow in importance.

On February 22, 2023, three days before the EU announced a ban on sending any semiconductor and microchip production equipment to Russia, Tefida’s shipments of exactly the same products on behalf of KBR-Technologies started ramping up. Over just three months, Ostec received almost $8.6 million worth of imports sent through Belarus by Tefida.

Tefida is owned by Belarusian citizen Maryna Kosmach; its director is her brother Alexander Shibko. When contacted by journalists, Shibko denied any involvement in sanctions evasion, although he acknowledged that the goods had moved through his company’s warehouse.

“We didn’t supply anything,” Shibko told Buro Media. “I didn’t sign any waybills for anything sanctioned. They also cleared customs themselves. We were simply a temporary storage warehouse.”

The co-owner of KBR-Technologies, Zhanat Ibraev, declined to comment, and the company did not respond to emailed questions. Ostec officials also did not respond to requests for comment.

In May 2023, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Ostec Group, their supplier Kostiouk, and his companies Inter-Trans and BMA Spedition, prohibiting anyone from doing business with them. Shortly after that, shipments from Kostiouk’s companies stopped being sent directly to the Ostec Group.

However, between April and August Tefida supplied about $2.5 million worth of high-tech equipment on behalf of KBR-Technologies to another Russian company, FabCenter LLC, which is tied to the Ostec Group through shared current and former owners.

Reporters have found no evidence that Kostiouk and his companies are still supplying Russian military contractors today. But similar schemes, operated by individuals who have not come to the attention of any sanctioning authorities, are likely still in operation, experts say.

The continued flow of sanctioned high-tech equipment into Russia might be bad news for Ukraine — but it also suggests that Russia is having trouble manufacturing these goods on its own.

“A significant share of the Russian imports of these goods still ultimately comes from Western companies,” said Benjamin Hilgenstock, a senior economist at the Kyiv School of Economics. “That’s good news and bad news at the same time. The good news is that Russia has not substituted them or been able to substitute them. … The bad news is obviously, well, if Russia is still buying these things then our export control enforcement is facing serious challenges.”

“These companies need to properly control their supply chains,” he added. “They say they can’t, but we think that that’s a cheap excuse, and ultimately it’s a question of incentive.”

Original investigation article follow the link: OCCRP