Joe Biden might be the perfect president to restore America’s standing as a champion against foreign corruption.

This article is part of Foreign Policy’s ongoing coverage of U.S. President Joe Biden’s first 100 days in office, detailing key administration policies as they get drafted—and the people who will put them into practice.

More than $550 billion of dirty money is laundered each year in the United States and European Union, the world’s two largest economies. The good news is that strongmen, drug traffickers, criminals, and kleptocrats may find it harder to park and hide their money thanks to recent U.S. and EU actions that tighten anti-laundering regulations, and expand monitoring and enforcement. But even more importantly, U.S. President-elect Joe Biden has made the fight against corruption a top domestic and national security priority, while the EU has long been concerned about illicit and untaxed money. Neither side can act alone on this global problem—coordinated action is needed to shut down safe havens for nefarious actors. High on the Biden administration’s agenda should therefore be a transatlantic anti-corruption action plan, which would help rebuild frayed U.S.-EU relations while bolstering the security of countries on both sides of the Atlantic.

The United States is one of the world’s largest havens for illicit cash and one of the easiest places to form anonymous shell companies, which must be at the center of anti-corruption efforts. A few examples: For many years before the scheme was shut down in 2015, the Iranian regime circumvented U.S. sanctions and used an anonymous corporation to purchase a skyscraper on New York’s Fifth Avenue worth as much as $1 billion and to collect millions of dollars in rent. During the 1990s and 2000s, the Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout—known as the Merchant of Death—used at least 12 shell companies in Delaware, Florida, and Texas to move funds related to his weapons-trafficking network. Mexico’s largest drug cartel, Sinaloa, secretly laundered millions of dollars in drug proceeds after purchasing a horse ranch in Two Ukrainian oligarchs, after laundering funds stolen from a bank in Kyiv through anonymous companies in Europe, used U.S. shell companies to purchase U.S. real estate and businesses; two Cleveland properties alone are worth $70 million.

But this year should be a turning point, both because of the Biden administration’s planned corruption-fighting efforts and a recent major step by the U.S. Congress to rein in shell companies. The National Defense Authorization Act, passed against outgoing President Donald Trump’s veto with bipartisan support on Jan. 1, included the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) that will, for the first time, require millions of U.S.-registered businesses to report their true beneficial ownership to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). This measure should make it harder for criminals and autocrats to set up anonymous shell companies to hide their money. While the new law only allows access to the federal beneficial ownership registry to law enforcement, intelligence agencies, and federal regulators—but not anti-corruption NGOs, foreign investigators, or private individuals—it is the first significant anti-money laundering legislation in the United States in two decades. A coalition of banks and other corporations, realtors, national security experts, anti-human trafficking groups, religious leaders, state government officials, and chambers of commerce supported this critical legislation.

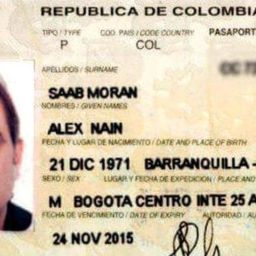

The U.S. Treasury Department now has one year to issue corresponding regulations. Once they are in place, many companies will have to disclose the name, date of birth, address, and the number of a driver-license or passport of the company’s beneficial owners. While this information can be falsified, a company submitting false information would face civil and criminal penalties. A weakness of this legislation is that existing companies will have another two years to comply once regulations are in place. An even bigger, more fundamental problem: Sectors such as private equity and hedge funds are exempt, as well as any business with more than 20 people, $5 million in gross receipts or sales, and a verifiable physical presence. During the three years before this law is fully implemented, it is expected that lobbying groups will try to carve out even more exemptions, which would be an unfortunate setback in the fight against corruption.

Along with the United States, Europe shares the distinction of being a global money-laundering center.

Denmark’s largest lender, Danske Bank, for example, remains under investigation in EU member states for an estimated €230 billion in suspicious transactions that flowed through its Estonian branch office to EU and non-EU jurisdictions. According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, much of this money was transferred through shell companies in the United Kingdom. European officials are also investigating how Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s wealthiest woman and the daughter of former Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos, used shell companies throughout Europe to hide hundreds of millions of euros, if not more, from unexplained sources. Meanwhile, her country remains desperately poor, ranking 148th among 186 countries on the poverty scale.

The EU, partly as a response, has been updating its money laundering directives. On Nov. 4, EU finance ministers approved the creation of a new anti-money-laundering watchdog that will have authority to intervene with national governments if they fail to comply with or enforce EU directives. This supranational body will also make it easier for law enforcement to act across borders.

While they are signs of progress, these laws and directives are not enough. The political will to implement and enforce them are key. And while the United States and the EU seem to want to put their own houses in order, only by working together will they be able to expose and prosecute those who are hiding billions of dollars obtained through corruption and crime. Therefore, the Biden administration should embark on a joint action plan with its European partners. Such a plan should include:

1. A top-level commitment to increase resources for investigators. U.S. and EU financial intelligence units are understaffed and underfunded. The Corporate Transparency Act gives FinCEN $10 million in new funds and the authority to hire more experts. That’s far less than Congress provided to FinCEN to fight terrorist finance under the 2001 USA Patriot Act, when the unit’s staffing was doubled to about 300. A similar increase in staffing and the use of technology such as artificial intelligence is needed given the new responsibilities under the Corporate Transparency Act, including the requirement to draft regulations in record time and to build an IT system for the new beneficial ownership database.

Digital currencies, digital front companies, and cryptocurrencies have created still more opportunities for money laundering.

2. Increased training—and joint training—of U.S. and European officials. The U.S. Treasury Department, State Department, Department of Justice, and Securities and Exchange Commission officials provide anti-money-laundering training programs, but their focus is on non-EU countries. Some EU financial intelligence units also need training to monitor and prevent cross-border and transatlantic flows of illicit money. As the U.S. ambassador to Cyprus, an EU country with a population of only 800,000 that is a favorite destination of and transit point for Ukrainian and Russian money of dubious origin, I saw firsthand the urgent need for a first-class, well-staffed financial intelligence operation.

3. Better use of the existing U.S.–EU Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty. The process established by this treaty is key to exchanging information between the U.S. and EU on money laundering and corruption. But the process is incredibly inefficient and can take years. I witnessed this as a deputy assistant secretary of state, when I pushed for long-delayed responses by EU member states to U.S. requests. A tighter partnership will be especially important to ensure a smooth and timely exchange of beneficial ownership information on suspect companies.

Kathleen Doherty, ForeignPolicy.Com