Proposal by Uzbek civil society activists

We are a group of Uzbek activists citizens concerned about the future of our country. We write because we understand the Swiss government may soon negotiate the return of several hundred million Swiss francs that were stolen from the people of Uzbekistan through corruption in the country’s telecom sector and hidden in Swiss banks. We urge the government of Switzerland to ensure that these assets are returned responsibly to Uzbekistan. By responsibly, we mean in ways that provide remedy to the citizens of Uzbekistan as the true victims of grand corruption and that ensure concrete measures to eliminate systematic corruption in Uzbekistan.

The need for responsible repatriation of stolen assets

Repatriation of stolen assets is responsible if it contributes to the fight against corruption on global and national levels.

Grand corruption in Uzbekistan is endemic and penetrates all levels of the political, administrative, legal, corporate, and financial institutions. A clear correlation is seen between corruption at the highest levels and the gross violations of human rights.

Therefore, a cautious asset return policy should be pursued. There is a high risk that without anti- corruption mechanisms in place unconditional return of the proceeds of corruption will very likely lead to funds being stolen once again and recycled anew into western and offshore jurisdictions.

Unconditional return of the proceeds of corruption would violate both the word and spirit of the UN Convention against Corruption, international human rights law, and the global framework for fighting corruption. UNCAC requires the return of stolen assets to the countries of their origin. States however cannot selectively comply with UNCAC provisions; they must comply with all provisions, including those requiring the establishment of anti-corruption prevention mechanisms.

If asset-holding states fail to ensure that the return of the proceeds of corruption serves as a deterrence to future crimes, this must be considered irresponsible, if not complicit with perpetuating corruption in the requesting state.

Proposed principles of asset restitution to Uzbekistan

At the Global Forum on Asset Recovery in December 2017, representatives of the Swiss and other governments agreed to principles to guide asset return. Among other things, the governments pledged that the return should guarantee transparency and accountability in the use of the assets returned, benefit the citizens of the receiving country, strengthen the receiving nation’s ability tofight corruption, and ensure civil society participation in the return and use of funds.

Below we propose eight guidelines that emphasize and elaborate on these principles in the context of any return of stolen assets to Uzbekistan:

- The asset return should be considered in the context of, and contribute to, the fight against corruption and human rights violations on global and domestic levels and meet standards of transparency and accountability.

- Therefore, there should be no return of assets without sound conditions and mechanisms to prevent the assets being stolen again.

- The asset return should serve as remedy for the victims of corruption, i.e., the entire population of Uzbekistan.

- The best remedy for victims is not compensation – which would neither be practical (withUzbekistan’s specific institutional environment) nor have any lasting long-term, systemic effect – but rather measures to reduce the scale of corruption and human rights abuse in Uzbekistan.

- Asset return should be used as an incentive to reform those specific institutional conditions that were and remain driving factors for the original crimes – bribery and extortion in the telecom sector of Uzbekistan – and consequent money laundering. Below we identify five such institutional conditions.

- Reforms cannot be implemented overnight, and will require several years. Therefore, the restitution process should be extended over time and follow a step-by-step approach, rewarding Uzbekistan for making benchmarked and measurable progress in realizing reform.

- Provided the principles 1–6 are satisfied, the Government of Uzbekistan should have control and ultimate approval over the disposition of the assets, following a transparent process inclusive of consultations with relevant international stakeholders and Uzbek civil society. The implementation of these principles would create a completely new reality in Uzbekistan in terms of the governance system and, as such, give sufficient assurances that the assets are not re-stolen and re-laundered.

- In case the government of Uzbekistan rejects these guidelines, the Swiss government should keep the assets until the Uzbek leadership accepts the deal and has shown legitimate and verifiable progress.

Five institutional sectors to be reformed as prerequisite for asset return

- Establish a transparent and competitive tendering process, including in the spheres of allocation of frequencies and licenses, the public procurement of goods, public works, and contracted services. Publish all material related to public procurement and concession contracts in the public domain.

- Reform the public administration to make sure civil servants carry out the duties of their role, abide by the law, and work in the public interest instead of acting out of personal loyalty to high-ranking officials. With this in mind, implement a conflict of interest regulation for all civil servants and government officials in Uzbekistan and provide full transparency of their income.

- Establish independence of judiciary and legal profession; enforce the rights for fair trail and due process;

- Ensure transparency of public and corporate finance, including: obligatory auditing of state and its major corporate contractors by reputable international auditors and the full publication of such audit reports in the public domain; disclose government books to the public, with an emphasis on export revenues; and administer a transparent system of corporate disclosure, with a requirement that all corporate entities operating in Uzbekistan participate in a public register of beneficial owners.

- Provide oversight including through the establishment of an independent public anti- corruption agency; and allow civil society and media outlets to freely operate and conduct journalist investigations without fear of harassment and repressions.

We note there are many widely recognized international indicators available that would measuregovernments’ progress in meeting these objectives (see annexed below discussion of Indicators for Gaging the Progress of Reform in Uzbekistan, prepared by members of the Working Group on Responsible Asset Repatriation).

Why specifically these five institutional conditions?

The complete absence of institutional integrity in the five sectors mentioned above were key enabling factors for the original corruption case. As such, these areas should be addressed as prerequisites for returning the proceeds of corruption to the Government of Uzbekistan. But what is right for the telecom industry can also be applied to other sectors of economy.

First, Uzbekistan did not at that time and still does not have an established system for transparent and competitive tendering processes, neither in allocating frequencies and licenses, nor in public procurement. Given the absence of transparent public procurement, it is very likely that unless appropriate reforms are implemented, the returned assets will be redistributed via opaque lucrative procurement contracts, a frequent practice if not the rule for use of public funds in Uzbekistan.

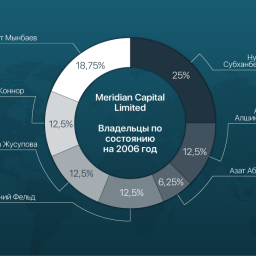

Second, Gulnara Karimova did not act alone in extorting bribes from telecom companies in exchange for issuance of operating licenses. Karimova would have been unable to carry out the original crimes without involvement of a number of government institutions. A number of high ranking officials were directly involved in issuing these licenses, and these individuals acted out

of personal loyalty to herself and her father, former president Islam Karimov. This highlights the systemic impact of the patronage system upon how public office was and still is run, and the total absence of conflict of interest regulation in Uzbekistan. It also demonstrates the lack of a civil service which works in the public interest and can withstand pressure from high ranking corrupt officials.

Third, it is notable that from the very beginning, western telecom companies sought back-door deals with local officials, instead of relying on judicial measures and legal means to engage in and protect their business and property rights. We understand western companies were well aware of the absence of rule of law and independent judiciary in the country.

Fourth, the public and corporate finance systems in Uzbekistan are extremely opaque. Neither the state itself nor its major corporate contractors are under obligation to open their finances to scrutiny by reputable auditors. Additionally, the state budget does not reflect income from export revenues the government controls, such as revenues from the cotton sector – linked to forced labor and human rights violations. Instead, these revenues go into hidden extra-budgetary accounts controlled by a few individuals around the President, and are used at the discretion of political elites on expenditures unknown to the public. It is unfortunately very likely that an unconditional return of assets to Uzbekistan will leave the state susceptible to repeating such practices; with the funds remaining absent from the state budget.

Fifth, essential monitoring, oversight and compliance institutions are absent. Uzbekistan does not have an independent anti-corruption state agency capable of independently detecting and preventing cases of government corruption. Uzbekistan also lacks an independent organized civil society – following a large-scale crackdown between 2004and2007 – or an independent press that would be able, without fear of repression or reprisal, monitor, document and report on corrupt practices, especially on cases of grand corruption. Activists and journalists who tried in the past to report on such cases were detained, tortured and imprisoned. While some of these journalists and activists have been recently released from prison, which constitutes a positive sign, they are still subject to reporting requirements, harassment, and other conditions inconsistent with full rehabilitation by the state. Nor have they been compensated by the state for their unjust imprisonment. In fact, legally, these individuals are still considered criminals according to the judicial system of Uzbekistan, and the original miscarriage of justice has not been addressed.

Our demand for serious changes in these five areas as part of the process for returning assets to Uzbekistan should not be seen as confrontational towards the government. The Uzbek political leadership has itself committed to reforms in these areas and has even made a few steps forward. For instance, a draft law on public administration has already been published, which still needs to be adopted and, more importantly, implemented. There has been also one case of fair trial open to the public (in March-April 2018, trial of Bobomurod Abdullaev and two others). So far, this is a single such precedent. Besides, there are some indications of opening for Uzbek press to report on controversial issues, though the press does not still dare to conduct journalist investigations into corruption cases. These positive signs do not yet represent fundamental or irreversible change. What is needed in Uzbekistan is not promise and rhetoric of change, but a sustained pathway to reform and the adoption of standards of good governance.

It still remains to be seen whether the government will adopt a full package of anti-corruption reforms and, more importantly, implement new legislation into actual practice. We believe that each significant step and improvement in these five areas should be rewarded, with a corresponding portion of assets returned to the government. Such a sequenced, benchmarked approach to restitution would be perfectly in line with the course of reform to which the new Uzbek political leadership has publicly committed, notably within Uzbekistan’s Development Strategy(2017–2021). The return of assets should reinforce the process of reforms, offering a guarantee that they will become sustainable and, over time, irreversible.

Why not a Bota Fund-like solution?

We believe that the creation of the Bota Foundation in 2009 as a channel for restituting Kazakhgate money to the people of Kazakhstan was the right decision. The latest restitution by Switzerland to Kazakhstan of $48 million, in 2012, was, by contrast, much worse, from the point of view of principles of responsible return.

An investigation was conducted into USD 21.76m of the restituted assets earmarked for a Youth Corps Program. It revealed that the Project Coordinator for the Youth Corps Program is a consortium made up of Government Organized NGOs (GONGOs). The consortium is headed bythe President’s eldest daughter, Dariga Nazarbayeva, who is a politician in her own right. This GONGO consortium will receive approximately USD 465,000 for its services as Project Coordinator. “From the limited available procurement data, — write the authors of the summary report, — examples have been uncovered of lavish spending on promotional material, awards tothe ruling party’s youth wing, expenditure on materials that have a propagandistic function, andthe selection of ‘host organizations’ that are predominantly GONGOs, some of which are run directly by public officials and politicians espousing strong commitment to the President’snational ideology.” 1 This resulted in restitution benefiting the ruling party and senior officials of Kazakhstan, but not the victims of corruption.

Under the current state of affairs in Uzbekistan, the Bota Fund-like solution cannot be applied without violating the principles of transparency and accountability and responsible return, because the conditions for operation of such a fund, independent from the government, do not exist.

First, the Bota Fund in Kazakhstan operated through allocation of grants to local NGOs which, in turn, delivered financial and technical assistance to low-income families. In Uzbekistan, such independent NGOs simply do not exist. Between 2004 and 2007, the relatively independent NGOs were suppressed, leaving Uzbekistan with no independent organized civil society. Due to repression inflicted by the Karimov regime, there are currently no stakeholders in Uzbekistan who could either provide Bota-like services to the population or conduct independent monitoring of how these funds are being used.

1 See Lasslett, K. and Mayne, T. (2018) A Case of Irresponsible Asset Return? The Swiss- Kazakhstan $48.8 Million, https://kiar.center/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/A‑Case-of-Irresponsible-Return-Summary-Report.pdf

Second, in the current absence of a transparent tendering and public procurement process in Uzbekistan, there is a very high probability that the money will be channeled through lucrative contracts to cronies of political elites, and thus stolen once more. Examples of such shadowy deals on the allocation of contracts on construction and reconstruction in Tashkent are multiple nowadays.

Third, without a transparent system of public finance, the government can manipulate the use of the returned assets. For example, it could cut funding it had planned to provide for health, education, and other social projects, divert these funds to private interests, and employ the returned assets to cover the gap in public funds. By shifting funds this way, the intended restitution would bear no positive effect for the people of Uzbekistan.

Finally, we believe that using the assets to reinforce anti-corruption reforms will be most beneficial for the victims of corruption and the development of Uzbekistan over the long term, supporting systemic, transparent institutional reforms with lasting effect.

Umida Niyazova, on behalf of Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights, Berlin, Germany,

Nadejda Atayeva, on behalf of Association for Human Rights in Central Asia, Le Mans, France,

Jodgor Obid, Uzbek political refugee, resident of Austria

Dilya Erkinzoda, Uzbek political refugee, resident of Sweden

Ulughbek Haydarov, journalist, former political prisoner, resident of Canada

Alisher Taksanov, journalist, political emigrant, resident of Switzerland

Alisher Abidov, political emigrant, resident of Norway

A number of local Uzbek activists support these proposals, but their names are not disclosed out of concerns over their safety.

Appendix

International Working Group on Responsible Asset Repatriation

INDICATORS FOR GAGING THE PROGRESS OF ANTI-CORRUPTION REFORM IN UZBEKISTAN

The Swiss and Uzbek governments are negotiating a return of Gulnara Karimova’s assets, stolenfrom the people of Uzbekistan and hidden in Swiss banks. Uzbek civil society activists are urging the agreement to include reforms of Uzbek institutions and ensure the assets are not again stolen, but are instead used to promote the welfare of Uzbek citizens. The reforms they seek are similar to those the United Nations, World Bank, and other donors include when providing financial assistance to governments.

The international community has developed a range of indicators to measure the progress a government is making in realizing such reforms. The reforms Uzbek civil society collectively urge, along with some of the key indicators used to mark progress in achieving each, are listed below. We urge the Swiss and Uzbek governments to incorporate these benchmarks into the asset return agreement. They should also agree on ambitious and realistic targets for improvingUzbekistan’s score on achieving genuine reforms, as funds are returned.

1) Establishing a transparent and competitive tendering process.

The World Bank’s annual Benchmarking Public Procurement reports how close nationalprocurement systems come to agreed upon standards of openness and competitiveness. Georgia’sInstitute for the Development of Freedom of Information has, with other organizations in Eurasia and Eastern Europe, devised a method for measuring how open and competitive procurement systems in the region are.

2) Creating a capable, independent, apolitical civil service.

Published annually, the World Bank Country Performance and Institutional Assessment rates how closely countries adhere to the principles of a merit-based, politically neutral civil service.Professors Peter Evans and James Rauch’s method for measuring the quality of a nation’s civilservice is widely employed by scholars and policymakers alike to evaluate public service bureaucracies.

3) Establishing an independent judiciary dedicated to enforcing fair trial rights and observing due process of law.

Gothenburg University’s V‑Dem project rates countries annually on the extent to which the executive respects the constitution and complies with court rulings; and extent to which the judiciary can act in an independent fashion. The World Justice Project and the Bertelsmann Transformation Index both publish a yearly assessment of how closely governments adhere to rule of law principles.

4) Ensuring a transparent public financial management system and transparency in corporate ownership and finance.

A partnership that includes the Swiss government, the European Union, and the IMF have developed the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Framework (PEFA), a now universally accepted system for assessing the transparency and effectiveness of public financial management systems. The Open Budget Survey assesses the public availability of budget information and other budgeting practices that contribute to an accountable and responsive public finance system. The Financial Secrecy Index administered by the Tax Justice Network provides internationally recognized benchmarks for corporate and financial transparency and compliance.

5) Strengthening accountability through establishing an independent anti-corruption agency and guaranteeing civil society and the media freedom to operate.

The World Bank gathers information from a variety of sources each year which it then compilesinto a scale showing “voice and accountability,” the extent to which a country’s citizens canparticipate in selecting their government, how free they are to express their opinions and create private, voluntary associations, and whether the media faces restrictions on what it can publish.

Federal Assembly of Switzerland

Swiss Federal Council

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA)

Federal Department of Justice and Police

Task Force on Asset Recovery, FDFA

Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, FDFA

PDF of this document is here.

How to return one billion dollars stolen from the people of Uzbekistan