As Kyrgyzstan’s new regime consolidates power, fresh allegations of corruption by Atambayev loyalists are emerging.

Until November last year, Almazbek Atambayev was the hugely wealthy president of Kyrgyzstan — although the sources of that wealth remain unclear. Now it seems that Atambayev is on his way out of the country, where there is talk of prosecution. Atambayev’s former prime minister is in prison and a loyal adviser has been deported. Just how did he reach the heights from which he now seems to be falling?

On 22 October, it was announced that Atambayev was flying to Moscow for the 10th General Assembly of the International Conference of Asian Political Parties on 24-27 October, as part of his role as chairman of the Social-Democratic Party of Kyryzstan. In the meantime, Atambayev has announced that he is travelling to St Petersburg for the funeral of a relative. Coming after the arrest and deportation of Ikram Ilmiyanov, Atambayev’s former driver and presidential adviser, on 20 October, this Central Asian state is starting to talk about the possibility of the powerful ex-president facing prosecution. As Edil Baisalov, a Kyrgyz activist and commentator, said on Twitter: “Almazbek Atambayev NEVER, never took part in international party conferences, never represented the SDPK [Kyrgyzstan’s ruling party] at high-level meetings. Participating in this third-rate conference in Moscow is just a pretext to FLEE Kyrgyzstan.”

Indeed, since Atambayev’s term in office ended in November 2017, the ex-president’s name has appeared in connection with cases ranging from the illegal privatisation of municipal property to the embezzlement of funds from infrastructure projects. In 2018, following presidential elections and a concerted campaign by Kyrgyzstan’s new president Sooronbay Jeenbekov to consolidate power, the allegations about the sources of Atambayev’s wealth have started to emerge. Publications implicating Atambayev and his close associates in corruption and illegal activities have started appearing in Kyrgyzstan’s mainstream media and on social networks.

Among the highest-profile cases, former prime minister Sapar Isakov is currently held at the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) detention centre. He is charged with corruption relating to lobbying in the Bishkek Heat and Power Plant scandal. Former Bishkek mayor Albek Ibraimov is also in GKNB detention as the authorities investigate two separate cases of corruption in which he is implicated.

There can be little doubt that Atambayev loyalists have fallen victim of the clash between the former president and Jeenbekov, a sometime ally turned foe. In reaction to the arrests of his closest associates, Atambayev issued a public statement in June this year, in which he claimed responsibility and oversight over projects associated with these new corruption investigations:

“Neither S. Isakov, former presidential Chief of Staff, nor the former mayor of Bishkek K. Kulmatov had the authority to independently take the decisions that are at the basis of these accusations. […] All strategic decisions for the reconstruction of the [Bishkek] Heat and Power Plant and the associated loan from China, including our agreement that the Chinese side appoint the contractor, the decision to redirect foreign grant funds… were made by me as the Head of State. The key role of the President in making these decisions is due the lack of responsibility among state institutions and employees.

The same applies to the implementation of other national projects […] including: […] the construction of an alternative North-South road, the transfer of Kyrgyzgazinfrastructure to the company Gazprom, construction of the Verkhne-Narynsky cascade of hydroelectric power plant, […] reconstruction of the History Museum and many other strategically important facilities and activities.”

What follows is an overview of what is known about Atambayev’s assets, as well as ongoing investigations against Atambayev loyalists.

Origin story

Atambayev, 62, has often publicly boasted about his wealth. In 2016, at a ceremony to receive the credentials of several foreign ambassadors, Atambayev claimed that his political career started when he was already a multi-millionaire.

Indeed, during a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in February 2017, Atambayev boasted (in the third person) that “Atambayev has never stolen! He made his own money! When Atambayev became a multi-millionaire, many of today’s millionaires were only starting their businesses! I was already a dollar multi-millionaire here!”

Atambayev’s business activity began in 1991 with the Kyrgyz Writers’ Union, where he gained control over the foundation’s assets. In November 1992, the Nooruz Writers’ Club – a large two-story building in Bishkek’s city centre owned by the Writers’ Union – was converted into a Joint Stock Company. Atambayev’s Forum company held 70% of the Nooruz shares, and Atambayev’s close relative Nurbek Sharshenov turned the premises into a restaurant.

In a 2014 interview from exile in Moscow, the first President of independent Kyrgyzstan, Askar Akayev, accused Atambayev of stealing a 50 million-rouble grant made to the Kyrgyz Writers Union by then Russian President Boris Yeltsin in the early 1990s. According to Akayev, the money was used to privatise state assets, such as a sheepskin and coats factory in Kant, a town 20 kilometres east of Bishkek, and the KyrgyzAvtomash factory for car engine radiators, which Atambayev headed from 1997 to 2005. In 2017, in a defamation case against the Zanoza news website and journalist Naryn Aiyp, the Kyrgyz General Prosecutor’s Office stated that Akayev’s claims had been disproven in a 2014 interview on Kyrgyz Television (KTRK). According to Aiyp, when the journalist asked the Prosecutor’s Office to present this programme (or a transcript) in court, they failed to do so.

Atambayev’s career in politics began as a member of parliament for the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan (1995-2000) – of which he was one of the founders – followed by stints as a Minister of Industry, Trade, and Tourism (2005-2006), Prime Minister (2007), and again Prime Minister for the interim government established after the ouster of President Bakiyev in the April 2010 revolution. In October 2011, Atambayev won the presidency in a landslide and served one six-year term (2011-2017) as stipulated in Kyrgyzstan’s constitution.

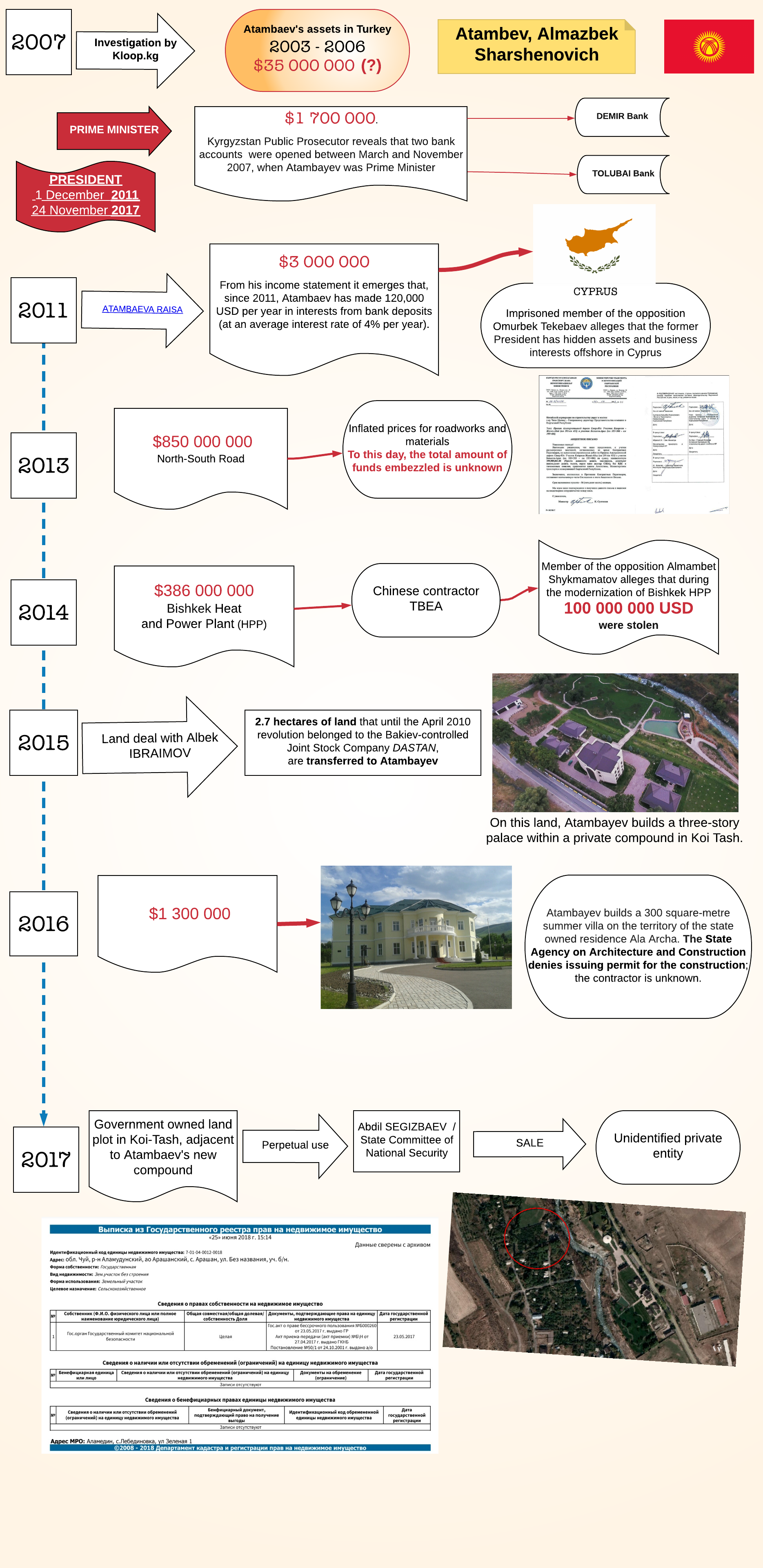

Atambayev is undoubtedly rich, but the origins of his wealth are less clear. For example, when, in 2017, Kyrgyz opposition politician Omurbek Tekebayev accused the former president of having business interests outside Kyrgyzstan, Atambayev argued that he had sold his stake in the Turkish company Elektromed Elektronik in 2003 for 45 billion Turkish liras (which, he added, was equivalent at the time to $35 million). When activist Edil Baisalov pointed out that, at the 2003 exchange rate, 45 billion liras amounted to $26,000, the press service of the Presidential Administration intervened to specify that the company’s market value was much more than its authorised capital.

When journalists from Kloop.kg, one of Kyrgyzstan’s best investigative journalism websites, requested Atambayev’s income statements for 2005-2006 in 2017, it was stated that the records had been destroyed. According to the State Personnel Service, the law requires public officials’ statements to be kept for six years, after which they can be disposed of

Living the life

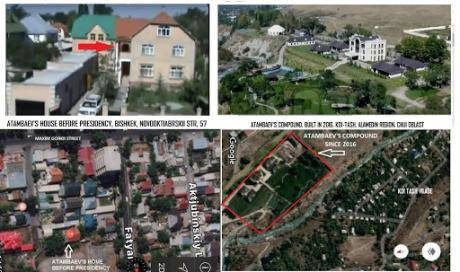

Atambayev’s declared income is quite modest. In 2010, he earned $5,944 as prime minister in the interim government. A monthly salary of $500 is good money in Kyrgyzstan, but it doesn’t make you rich. By 2015, according to official records, Atambayev had accumulated $111,205, while Raisa Atambayeva, his wife, had $580,860 to her name. That said, the Atambayevs’ lavish properties reveal that the former first couple can count on much larger financial resources, which apparently increased significantly during Atambayev’s presidential rule and whose origin remains unknown.

One such property is the three-storey palace in the former president’s compound in Koi Tash, south of Bishkek. This site was built in 2016 and is equipped with gazebos in a luxurious private park. Before being elected president, the Atambayevs lived in a nondescript house in a dusty eastern district in the capital.

In March 2018, Atambayev built a 300-square-metre summer villa on the territory of the official (and state-owned) presidential residence in Bishkek. The total cost of construction was reported to be approximately $1.3 million – in Kyrgyz currency, 89.3 million som. While 77.8 million som came from Atambayev’s private funds, the origin of the remaining 11.5 million remains unknown. Attorneys from the Jakupbekova & Partners Law Firm requested information regarding this project from Kyrgyzstan’s State Agency for Architecture and Construction, which, in a letter obtained by openDemocracy, denied having given permission for the construction. Likewise, the contractor’s name is unknown.

Alleged corrupt deals

Since Atambayev left office at the end of 2017, a serious rift has emerged between him and current president Sooronbay Jeenbekov, which has split their Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan.

Here follow several allegations of corruption that have been made following the end of Atambayev’s presidency. Former prime minister Sapar Isakov, whom Atambayev described as his “right-hand man” to visiting German Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2016, appears in connection with all these cases. In a statement to Open Democracy, Nurbek Toktakunov, legal counsel to Sapar Isakov, said that his client is being “persecuted by the new regime”: “He [Isakov] was under a ‘black media campaign’ by state media and state trolls on social media for several months to ‘justify his arrest’.”

Attempted lease of helicopters to Uganda

As I detailed recently in The Diplomat, in 2014 Atambayev signed off an order to lease two Mi-24V and two Mi-8MTV helicopters to Uganda under Sapar Isakov’s supervision.

Instead of paying through official channels, the contract committed Uganda to paying for the lease through a company based in the United Arab Emirates. After then-Minister of Defence Abibilla Kudaiberdiyev demanded a judicial review of the deal, the military prosecutor’s office declared this deal to be illegal. So did the inter-ministerial commission that looked into the case, but apparently no one has been held accountable.

The lease cost remains secret. In 2015 Isakov warned the chief of staff of Kyrgyzstan’s armed forces that “failure to execute the deal will cause a loss of $30 million”. In the end, the deal did not go ahead.

North-South Road

At the May 2014 opening ceremony of the North-South Road, an artery connecting Kyrgyzstan’s two main cities – Bishkek in the north and Osh in the south – Atambayev declared that this was a historical event whose significance would be understood only four years later, once the road would be completed. Four years later, details have emerged of the extent of corruption that marred this road construction project.

In June 2018, the Fergana news portal published documents alleged that the Kyrgyz authorities and the Chinese contractor China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) colluded to embezzle funds from the Chinese government’s infrastructure investments by overpricing numerous items. Price tags on the project were inflated by several orders of magnitude, from paying $1.10 per kilogramme of cement (cost on the local market: 7¢) to paying $2,000 per month to provide office space to an engineer on the construction site.

Current Minister of Transport and Communications Zhamshitbek Kalilov, who, according to someone familiar with the situation is one of former Prime Minister Sapar Isakov’s protégés, oversaw the project, along with his predecessor Kalykbek Sultanov. Commenting on these allegations of embezzlement appearing on Kyrgyzstan’s online media, Kalilov told Radio Azattyk that “someone is distributing unsubstantiated information.”

According to Kyrgyz MP Almambet Shykmamatov, no investigation into this case is ongoing.

History Museum refurbishment in Bishkek

In March 2016, Atambayev launched an ambitious renovation project for the Kyrgyz History Museum in Bishkek under Sapar Isakov’s supervision, as he himself told an interviewer on April TV in April 2018. “This will be the pride of Kyrgyzstan. A museum that we can be proud of,” Isakov commented. “Because during the reconstruction I was the curator, followed the progress of reconstruction and the whole process.” Two years later, opposition MP Kanybek Imanaliev claimed that $13 million of public funds had been stolen during the works. The museum, Imanaliev claims, was restored without a proper tender process and project documentation being drawn up.

As Kloop.kg website reported, the project costs appear inflated. €394,000 was spent on consultancy and design, while €224,000 was earmarked for a bar counter and furniture for the museum cafe, among other very expensive items. Moreover, 19,000 square metres of granite and marble blocks imported from Turkey disappeared from the site.

Czech investor Liglass

In July 2017, the presidential administration press service circulated a statement detailing that Czech company Liglass Trading CZ, SRO, had agreed to buy 50% of the shares of Joint Stock Company Verkhne-Naryn hydroelectric power stations from Russian company RusHydro for $37 million. Previously, in December 2015, the Kyrgyz government had rescinded the 2012 agreement with RusHydro to build small hydroelectric power stations on the Naryn river due to lack of funding.

As Kaktus media website reported at the time: “Agreements were signed between the Kyrgyz government and the Czech company in the presence of Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev.” The president solemnly declared: “The arrival of large private investments from Europe will serve as a powerful signal for potential investors from around the world.”

The deal is surrounded by questions about why the Kyrgyz government would commission a contract worth several hundred million dollars from a company in the red with a turnover in the tens of thousands of euros. According to Czech media, no one in the Czech republic seemed to know about Liglass before the company shot to fame in connection with the Kyrgyz deal. According to Marat Dzhonbayev, the Czech Republic’s honorary consul in Kyrgyzstan, Vratislav Mynář, the head of the Czech president’s office, reportedly recommended the firm to Sapar Isakov, after which Czech President Miloš Zeman and then-President Atambayev discussed the company at the opening ceremony of Expo 2017 in Astana, Kazakhstan.

And yet, why would Isakov and Atambayev still be willing to engage with Liglass when, after conducting research on the company, in March 2017 the embassy of Kyrgyzstan in Austria had clearly recommended that Bishkek discontinue any cooperation with the company as they “could not find any evidence of [its] successful implementation of investment projects abroad”?

The Kyrgyz Embassy added that Liglass had gone bankrupt. The deal with Liglass was eventually cancelled in September 2017.

The general director of Liglass Trading states that the company “was specially separated from a group of companies under my control, specifically for this project in Kyrgyzstan”, and that the company has experience in hydroelectric projects in Czech Republic, Slovakia, Italy, United Kingdom, Romania, Serbia, Chechnya and India.

Heat and power plant scandal in Bishkek

On 4 April 2018, the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) brought chargesagainst a number of Atambayev officials in connection with a $386 million Chinese loan to refurbish Bishkek’s heat and power plant.

Former PM Sapar Isakov was among those arrested. In a 2013 letter, Isakov had reported back to Atambayev himself with details of the power plant project. While members of the Kyrgyz parliament allege that $100 million was stolen from the loan, at the time of writing Atambayev hasn’t been linked to the investigation.

You scratch my back, I scratch yours

While the presidency has allowed Atambayev to reap huge financial benefits, he has generously rewarded his friends and associates with posts, power and money.

Albek Ibraimov

In 2016, Atambayev catapulted his former car mechanic Albek Ibraimov to the post of Bishkek mayor despite the latter’s lack of relevant education.

Indeed, under Atambayev, Ibraimov’s star had already soared. from 2010 to 2011 he was head of Bishkek Free Economic Zone; then spent a year as the head of state concern Dastan, a torpedo manufacturer, followed by a year as deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration. From 2013 to 2016 he was chairman of the board of directors at Manas International Airport before becoming mayor of Bishkek, a position he held until this year.

Like Atambayev, Ibraimov lived modestly prior to 2010. Journalists have uncovered the many properties Ibraimov did not declare in his income statements, including a 50-hectare estate with a manor in Arashan village, half-an-hour south-east of Bishkek.

The estate is surrounded by a three-metre brick wall stretching for 3.5 kilometres around the property. Armed guards patrol the perimeter.

Ibraimov’s luck appears to have run out, however. In June 2018, he was arrested on charges of corruption. He is accused of misappropriation and embezzlement during his tenure at Dastan, where he allegedly inflated the prices for the purchase of spare parts. A month later, Ibraimov was charged on another count of corruption for the illegal allocation of municipal land south of Bishkek while serving as mayor. Currently, Ibraimov is held at the GKNB detention centre. The investigation is ongoing.

“Voditel”

Ikramjan Ilmiyanov is Atambayev’s former chauffeur, hence the nickname “voditel’” (“driver” in Russian). Ilmiyanov had his career fast-tracked to presidential advisor due to his total dedication to his boss (legend has it that he literally savedAtambayev’s life by smuggling him into Tajikistan in the early 2000s when he was wanted by Akayev).

During Atambayev’s tenure, Ilmiyanov amassed considerable assets and even made it onto Kyrgyzstan’s rich list. In 2011, he acquired a 143.6-square-metre apartment on Bishkek’s central Chui avenue, as confirmed by a statement from the state registry service obtained by openDemocracy.

In 2016, Ilmiyanov’s two daughters entered the private Sagemont school in Florida, US, where tuition fees exceed$20,000 per student per year. That same year, Ilmiyanov’s declared annual income was $4,500.

An investigation by Azattyk stated that Ilmiyanov is affiliated with the IHLAS construction company and made an allegation that he is involved in the illegal acquisition of land in Bishkek. Following the arrest of other Atambayev’s associates, Ilmiyanov left the country. On 20 October, Ilmiyanov was detained in Russia and returned to Bishkek to face corruption charges.

Island of corruption

Since independence in 1991, Kyrgyz officials have been linked to everything from protection racketeering to drug trafficking, misappropriation of public funds, bribes, extortion, kidnapping and ransom.

According to Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index, Kyrgyzstan ranks 135 among 180 countries, preceded by Iran and followed by Lao. More than an “island of democracy”, as it used to be known after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan is an island of corruption. It is hard to distinguish where the criminal underworld ends and the official upperworld begins: politicians and criminal groups in the country live in symbiosis.

International criminal Kamchi Kolbaev lives cheek by jowl with public figures. As the US Department of the Treasury reported in 2012, Kolbaev is the Central Asia overseer for the Brothers’ Circle crime syndicate, which is involved in narcotics trafficking, among other things. As a consequence, then US President Barack Obama singled out Kolbaev “as a significant foreign narcotics trafficker under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act”. The US Treasury Department states that he is “is wanted in Kyrgyzstan for organized crimes and crimes involving the use of weapons/explosives, and organized/transnational crime”. And yet, a video emerged in May 2018 showing former prosecutor general Elmurza Satybaldiev attending the celebration of Kolbaev’s mother’s birthday.

It is a well known fact that illicit funds have been moved out of Kyrgyzstan to purchase luxurious real estate. As corruption watchdog Global Witness has amply documented, Maxim Bakiyev, son of former President Bakiyev, set up a money-laundering scheme that siphoned $1.2 billion through accounts in Citibank in New York, Standard Chartered in the UK and Raiffeisen Zentralbank in Austria. Eugene Gurevich, a financial advisor to Maxim Bakiyev currently serving a prison sentence in the US for fraud, confirmed these schemes in a recent interview.

After fleeing Kyrgyzstan in April 2010, the former minister of industry, energy and fuel resources, Saparbek Balkibekov, purchased a small British island in the Atlantic Ocean. According to former MP Bakytbek Beshimov, the alleged source of his enrichment was the illicit sale of 116 million kilowatts of Kyrgyz electricity through a company in the British Virgin Islands, causing an energy crisis in the country.

The conflict that has erupted between Atambayev and Sooronbai Jeenbekov, his former ally and appointee, raised hopes that the new president may steer the country towards real change. That hope was short-lived, however. Under the current government, people connected to former president Bakiyev’s administration are staging a comeback. Official posts continue to be handed out on the basis of favouritism and clientelism. A case in point is the recent appointment of construction magnate Aziz Surakmatov as the new mayor of Bishkek, despite his long record of construction and land laws violations, and the obvious conflict of interest.

Given the looting of state resources, and the rampant corruption in Kyrgyzstan’s law enforcement and judicial bodies, it seems a safe bet that Jeenbekov’s presidency will continue Atambayev’s legacy with only a different cast of actors. While the two former allies fight it out, the people of Kyrgyzstan are left with only crumbs on which to survive.

The author would like to thank Tom Mayne and the Kazakhstani Initiative on Asset Recovery (KIAR) for their assistance in researching this article.

By SATINA AIDAR

What we know about alleged elite corruption under former Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambayev