Britain is trying to turn round its reputation as a haven for ill-gotten gains

In their private mansions dotted in the Surrey hills and luxurious apartments in upmarket London mews, dozens of oligarchs enjoy the trappings of British wealth.

Their children go to the most expensive schools, their spouses wear designer clothes and they drive the best cars. They invest in universities and other respectable institutions to bolster their reputations, which are fiercely guarded by PR companies on eye-watering retainers.

Some are Russians grown fat from the spoils of President Putin’s regime. Others are businessmen with links to Middle Eastern dictators or drug traffickers from Nigeria. In many cases their money comes from bribery and corruption.

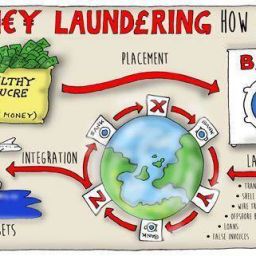

Britain, and its property market in particular, has long been known as a safe haven for ill-gotten gains. Transparency International claims that it has identified £4.4 billion of property that it suspects was sourced from illicit wealth, and the National Crime Agency warned in 2015 that property purchases using laundered money were driving up house prices.

Britain has a poor record of recovering illicitly obtained property not only from outright criminals but also from politicians and business figures suspected of corruption. Campaigners hope that this might change as powers are introduced allowing police to seize property much more easily.

Unexplained wealth orders (UWOs), which came into force this week, will require individuals suspected of serious crime or involvement in bribery or corruption to explain the source of property valued at more than £50,000. For the first time the law also extends recovery powers to cover “politically exposed persons”, although they have to be from non-EU countries.

The National Crime Agency (NCA) is understood to be considering two test cases with several others potentially to follow. Although UWOs can apply to all nations, Russians are expected to be a specific target.

If a High Court judge is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to suspect that a target is a criminal, a UWO can be issued. If the suspect refuses to explain the source of their wealth, the authorities can move to seize the property under the Proceeds of Crime Act. To complete this process they will have to prove that the property was obtained illegally — potentially a difficult task.

Even under the old regime some oligarchs had their properties confiscated. They include Mukhtar Ablyazov, a Kazakh businessman accused of embezzling billions of dollars, whose country estate was sold for £25 million. He was convicted of contempt of court in 2012 after a High Court judge found that he had breached an order freezing his assets. After he fled Britain his luxury home, which had an indoor swimming pool, was seized and sold.

In 2016 a £1.5 million Mayfair apartment belonging to a disgraced Russian banker was seized by the NCA along with £230,000 that she held in two bank accounts. Elena Kotova, former executive director of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), was ordered by the High Court to comply with a civil recovery order to surrender suspected criminal assets. She was a diplomatic representative sent to the EBRD to represent Russia.

Ms Kotova, who lived in London while at the bank, now lives in Moscow. Police said that if she were to return to Britain she would be arrested on suspicion of bribery and corruption offences.

Numerous Russians have also tussled with the High Court over their affairs. They include Sergei Pugachev, an oligarch who a judge ruled in October had hidden millions of pounds in five “sham” trusts. The Financial Times said that the trusts included properties in Battersea and Chelsea in London.

Senior law enforcement officials described UWOs as a useful weapon rather than a silver bullet in the fight against crime and corruption. One senior source said: “The UWO is an investigative tool, it is an order requiring someone to provide an explanation — it is not without its difficulties and it is not a panacea.”

Rachel Davies Teka, head of advocacy at Transparency International, said that there was “lots of low-hanging fruit” to be seized. “We are complicit as a country in global corruption. Money is being taken out of health and education in countries around the world because we have this system which hides wealth,” she said. “Hopefully with UWOs the UK can become a more hostile environment for corrupt wealth.”

Fiona Hamilton (Crime and Security Editor), Sean O’Neill (Chief Reporter)

Unexplained wealth orders are new weapon in war on illicit assets