Michael and Rose Vella, parents of anti-corruption journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, join a protest marking eighteen months since her assassination, outside the office of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat in Valletta, Malta, in April 2019. Credit: Reuters/Darrin Zammit Lupi (via Alamy)

Daphne Caruana Galizia’s work uncovering corruption in Malta delved into visa-for-sale schemes, energy deals, and Caribbean offshore companies set up for Maltese politicians. Now, an investigation has found that all these stories come together — in China.

For a tiny country, the Mediterranean island nation of Malta has spawned a huge number of corruption scandals — and Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia covered most of them on her crusading blog, Running Commentary.

She was one of the first to report on 17 Black, a mysterious Dubai company that she believed was linked to senior Maltese officials. She also dug into dubious circumstances surrounding a 2014 agreement to sell a major stake in Malta’s only electricity company to a Chinese state-owned firm, and a suspicious subsequent investment in a Montenegro wind farm. And in 2016, she seized on a Chinese media report claiming that Malta would be selling residency visas to wealthy Chinese citizens — with no questions asked about the source of applicants’ funds.

But Caruana Galizia didn’t live to see the end of these stories, even as her work caused them to emerge as hot-button political issues in Malta, leading to multiple corruption cases and even criminal charges against members of the country’s political elite.

In October 2017, just a few hours after publishing a final blog post — “There are crooks everywhere you look now,” it warned — Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb. Her assassination triggered a scandal that exposed corruption at the heart of Malta’s government, toppled its prime minister, and sent shock waves throughout the European Union.

Three people have since been imprisoned in connection with the murder. In a Valletta court this month, one of them, a hired hitman, said Caruana Galizia had been killed because she was about to publish “some details” on an unspecified topic. The alleged mastermind of the bombing, the Maltese tycoon Yorgen Fenech, is in jail awaiting trial.

Now journalists from OCCRP and partners have followed a trail of clues unearthed by Caruana Galizia from Malta to China, where they discovered two figures who tie together these stories she had been following — the 17 Black corruption scandal, the dubious energy deals, and the residency visa-for-sale program.

“What has become clear through these scandals is that they always end up leading back to the involvement of the same sets of people,” her son Matthew Caruana Galizia told OCCRP after reviewing the findings of the new investigation.

“It’s a clear indication of how, in a very short time span, a few individuals were able to take over the entire state apparatus of an EU country and turn it into a pirate ship for their own personal benefit.”

Credit: REUTERS/Darrin Zammit Lupi Activists from Occupy Justice Malta hold up placards reading “Who Owns Macbridge?” outside the office of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat in Valletta, Malta, on December 16, 2018.

Two Mysterious Companies: 17 Black and Macbridge

After Caruana Galizia was killed, journalists around the world raced to look into the topics she had been covering, including 17 Black. She’d posted repeatedly about the company and suggested it was tied to top politicians, but never managed to prove the claim.

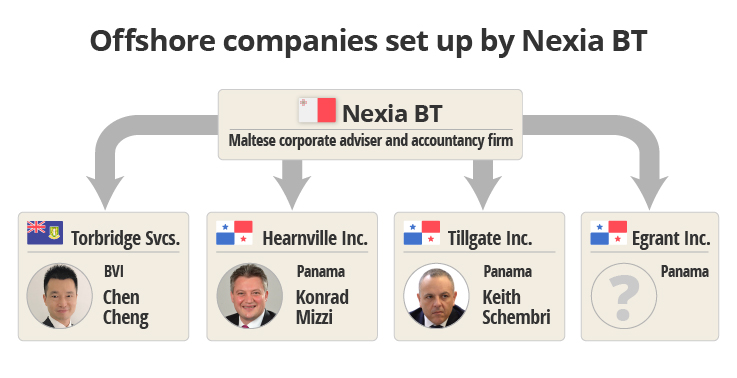

In 2018, Reuters and the Times of Malta revealed that 17 Black was owned by Fenech, a flashy local businessman with an alleged taste for cocaine and racehorses. He was close to some of Malta’s most powerful political figures — including Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and his chief of staff, Keith Schembri — and helmed a conglomerate that was part of a consortium that in 2013 won a major concession to build a 450-million-euro power station.

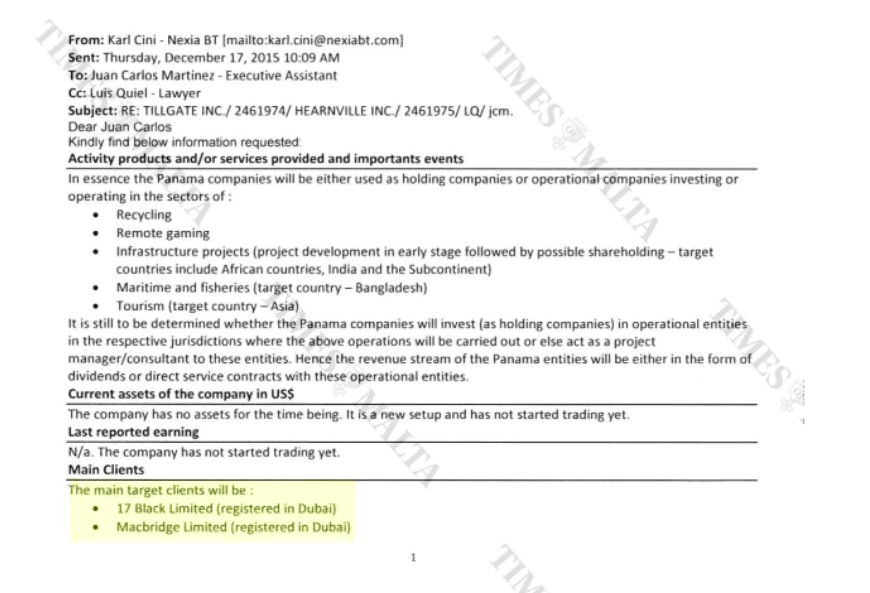

Fenech was apparently using 17 Black to funnel bribes to politicians. The story cited a critical piece of evidence: a leaked 2015 email sent by Maltese accounting firm Nexia BT, saying that 17 Black was expected to send up to $2 million to shell companies set up in Panama by two senior Maltese politicians: Schembri and Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi.

But what wasn’t widely reported was that another mysterious company was also named in the email as a source of funds for Mizzi and Schembri’s companies. It was referred to in the press only as “Macbridge.”

Caruana Galizia had also been quietly digging into the company, after learning of the same email in 2016 and hearing from a source that Macbridge and 17 Black were “crucial to unravelling the web,” according to her son and records of her work seen by reporters.

But Macbridge proved harder to trace than 17 Black and Maltese officials have refused to answer questions about the company’s existence. When then-Finance Minister Edward Scicluna was asked by a reporter last year who owned Macbridge, he retorted: “Look, if you want to be sensational, continue.” Journalists believed it to be a United Arab Emirates company, like 17 Black, but no trace of it was ever found there.

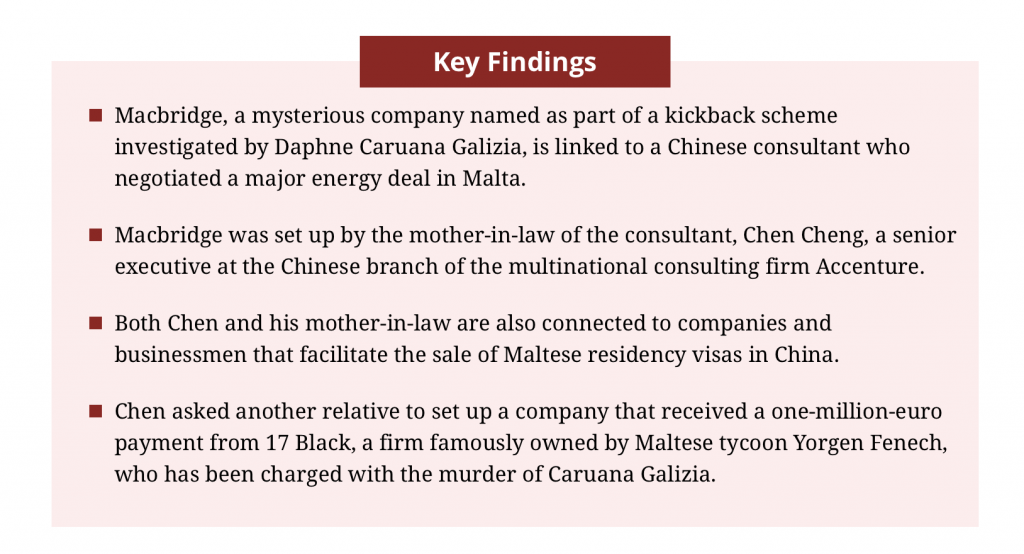

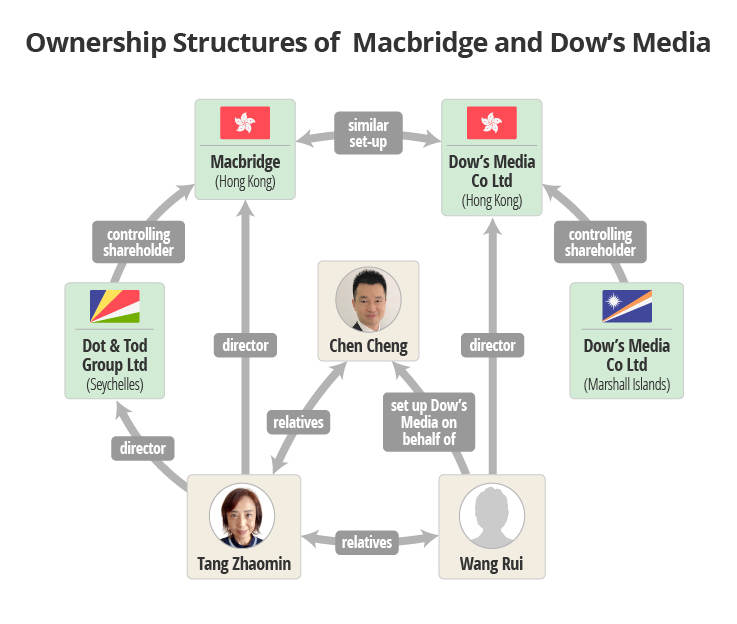

That’s because the company’s roots are actually halfway across the world, in Hong Kong, OCCRP and its reporting partners have discovered. The company is registered there as “Macbridge International Development Co Ltd,” along with a Chinese name that combines the characters for “Malta” and “China.”

Reporters also found that in mid-2016, 17 Black sent 1 million euros to another Hong Kong company, Dow’s Media Co Ltd, that shares a very similar set-up and structure to Macbridge.

Dow’s Media was incorporated in October 2014, just weeks after Macbridge, using the same Hong Kong-based formations agent and the same registered addresses in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Both companies were dissolved within a week of each other in January 2019.

Investigators in Malta sought details about both companies from Hong Kong and China in 2018 as part of an investigation into “possible corruption and money laundering.”

Macbridge and Dow’s Media are set up in ways that make it difficult to determine who actually owns them, controlled through shell companies in the Seychelles and the Marshall Islands, respectively.

But reporters found they are both directed by proxies with family ties to one man: a Chinese consultant at the center of major deals involving Malta’s government-backed energy utility, Enemalta.

The Chen Cheng Connection

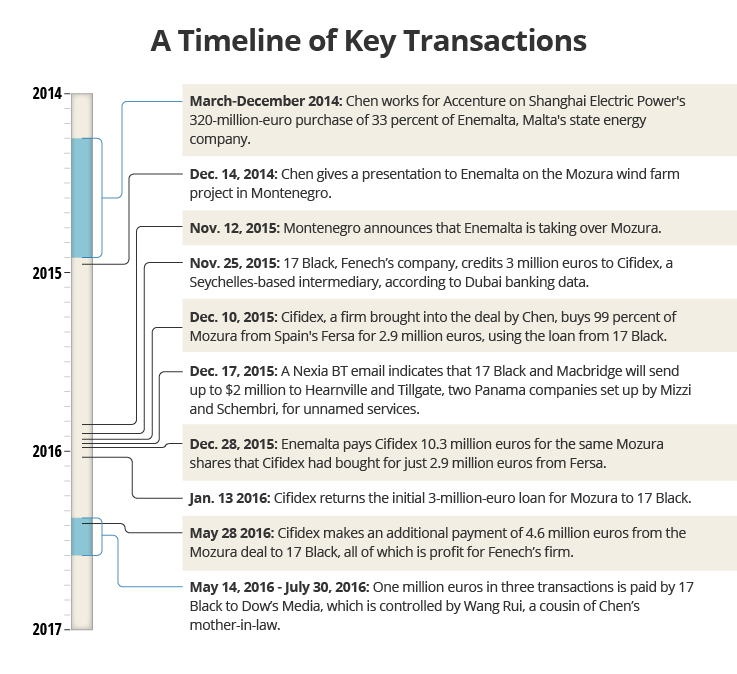

Caruana Galizia had been writing extensively about this man, Chen Cheng, a managing director of the Chinese energy division of global consulting firm Accenture. Chen emerged as a key player in negotiations for a 2014 deal for China’s state-owned Shanghai Electric Power to buy a third of Enemalta.

The deal was worth 320 million euros, the largest ever foreign investment in the country, but drew criticism in Malta — and on Caruana Galizia’s blog — for granting the Chinese company overly favorable terms.

Accenture advised Shanghai Electric Power on the deal, and Chen touted it in Chinese media as a landmark Belt-and-Road project endorsed by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

Caruana Galizia reported that a source told her Chen was “particularly close to Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi,” who oversaw negotiations on the Maltese side. (A subsequent inquiry unearthed emails between Chen, Mizzi, and others about a plan to set up an agency in China that same year to promote investment in Malta.)

She also revealed a key detail about Chen: When the accounting firm Nexia BT helped Schembri and Mizzi register secret companies in Panama, it also created a company for Chen in the British Virgin Islands.

But what Daphne didn’t know was that Chen was also connected to the offshore companies at the heart of the kickbacks scandal she was untangling — and the residency visa schemes she’d long harbored suspicions about.

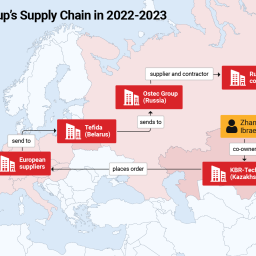

Macbridge and Dow’s Media were both set up in Hong Kong around the same time Chen was working on the Enemalta deal, by two of his family members: Tang Zhaomin, his 65-year-old mother-in-law, and Wang Rui, his mother-in-law’s cousin.

Reporters tracked Wang to the eastern Chinese city of Nanjing, where she and Tang own a company that operates local branches of the fast food chain KFC.

She said in a phone interview that Chen had asked her to open Dow’s Media, because its connection to a Chinese state-owned enterprise made it “inconvenient” for him to do so himself. She said she knew nothing about its business activities or its receipt of 1 million euros from 17 Black.

Tang could not be reached for comment. However, the new evidence linking the company she directs, Macbridge, to her family member, Chen, suggests that the Chinese businessman played a role in channeling money to the secret Panama companies of Schembri and Mizzi.

Money from what? It’s unclear, but following the successful Shanghai Electric Power investment in Enemalta, Chen became a key promoter of a subsequent 2015 Enemalta investment in the Mozura wind farm project in Montenegro.

According to an internal Enemalta investigation, Accenture advised on this investment in December 2014, with Chen pitching the idea to Enemalta in a PowerPoint presentation.

The investigation raised serious concerns about the deal, in which Fenech also played a role.

His 17 Black secretly helped fund the December 2015 purchase by Enemalta of a controlling stake in the project for 2.9 million euros, via a loan to a Seychelles intermediary called Cifidex Limited. That company, which Chen had brought into the deal, subsequently sold its shares in the project to Enemalta for 10.3 million euros just two weeks later, reaping a huge profit.

Cifidex then repaid the loan to 17 Black along with 4.6 million euros in profit from the deal. 17 Black, in turn, sent 1 million euros to Dow’s Media around the same time, from May to July 2016.

Although OCCRP has not uncovered definitive proof that this was the same money, the new evidence suggests that Chen was not only involved in facilitating secret money flows for top Maltese politicians, but also benefited himself from the 17 Black pipeline.

A spokesperson for Enemalta said by email that the internal report on the Montenegro-Mozura deal “was passed on to the Police to assist in any investigations. Any further comments at this stage would be imprudent.”

Questioned on Chen’s alleged activities surrounding the energy deals and offshore companies, and about his apparent conflicts of interest, Accenture said in a statement: “We are taking this matter very seriously and are carefully reviewing these allegations as they relate to one of our people. We adhere to the highest ethical standards in every market in which we operate and have zero tolerance for any deviation from those standards.” Chen himself did not respond to requests for comment.

Mizzi said by email that he had “no information” about Macbridge or anybody connected to it, adding that he has “consistently rejected the assertion that there is a connection, direct or otherwise,” between his company and Macbridge.

“I also reject the suggestion that I had business plans with Macbridge, or a personal interest in any public project,” he said. “I know Chen Cheng as a consultant assisting [Shanghai Electric Power] in multiple initiatives, and my interactions with him were in that official context.”

Schembri did not respond to a request for comment. In recent days, Maltese prosecutors have charged him, his father, and nine business associates, including Nexia BT employees, with fraud and money laundering over an unrelated case.

A ‘Nose for a Story’ Leads to Shanghai

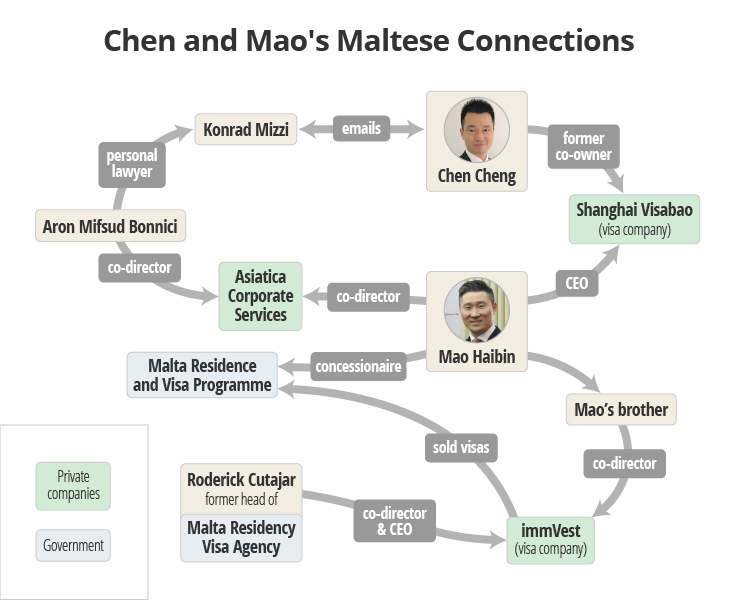

Chen and his mother-in-law aren’t just involved in offshore companies and energy deals. Reporters found they also have ties to one of Malta’s biggest businesses: selling citizenship and residency visas to wealthy foreigners, who can use the island as a backdoor into the European Union.

These ties run through a Shanghai businessman who effectively controls the sale of Maltese residency visas in China — through the same company Caruana Galizia highlighted in her 2016 blog post.

At the time, she had little more to go on than a single media report and a photograph showing a signing ceremony for the launch of the Malta Residence and Visa Programme in China, presided over by Konrad Mizzi’s wife, Sai Mizzi Liang. But “instinct, experience and the nose for a story” told her there was more to the situation.

“The next step that needs to be taken here — please, other journalists get on board with this one — is to find some way of checking out the shareholding and involvements of that company in China, which is going to be very difficult but necessary,” she wrote.

Caruana Galizia was right that it’s difficult to track down companies in China. Although the country does have a business registry system, the information within is often unstructured or incomplete, and it can only be navigated by someone fluent in Chinese.

But after months of research, reporters found that Shanghai Overseas Exit-Entry Services Co Ltd, which holds the official concession to sell Maltese residency visas in China, is run by a businessman named Mao Haibin, also known as Kevin Mao.

Chinese records show that Mao has ties to both Chen and his mother-in-law — the woman who directs Macbridge.

Mao and Chen were partners in at least two companies, including Shanghai Visabao Network Technology Co Ltd, which operates in several major Chinese cities and helps Chinese citizens procure visas abroad.

Chen’s mother-in-law is a manager and shareholder at a Shanghai advertising agency controlled by Mao, which in turn was a major sponsor of Malta Residence and Visa Programme events in China.

Mao, who did not respond to requests for comment, has multiple other business interests related to facilitating Chinese investment abroad — and in Malta specifically.

Over the past few years, he has played a major role in Malta’s efforts to attract wealthy Chinese nationals to its visa-sale program. He appeared at multiple events in Shanghai to promote the program, alongside senior Maltese officials like John Aquilina, Malta’s ambassador to China and Aldo Cutajar, Malta’s former consul general to Shanghai.

Some of these events featured lavish banquets attended by top Maltese diplomats, with plenty of warm testimonies to Malta’s status as a “key node” in China’s “Maritime Silk Road.”

But Malta’s citizenship-for-sale industry has been plagued by controversy. In August 2020, Aldo Cutajar was arrested by Maltese authorities and charged with illegally profiting from visa sales in China, and laundering the proceeds. During a search of his home, they found more than 540,000 euros in cash and four Rolex watches. The following month, Schembri was also arrested for allegedly taking kickbacks from selling Maltese passports to wealthy Russians.

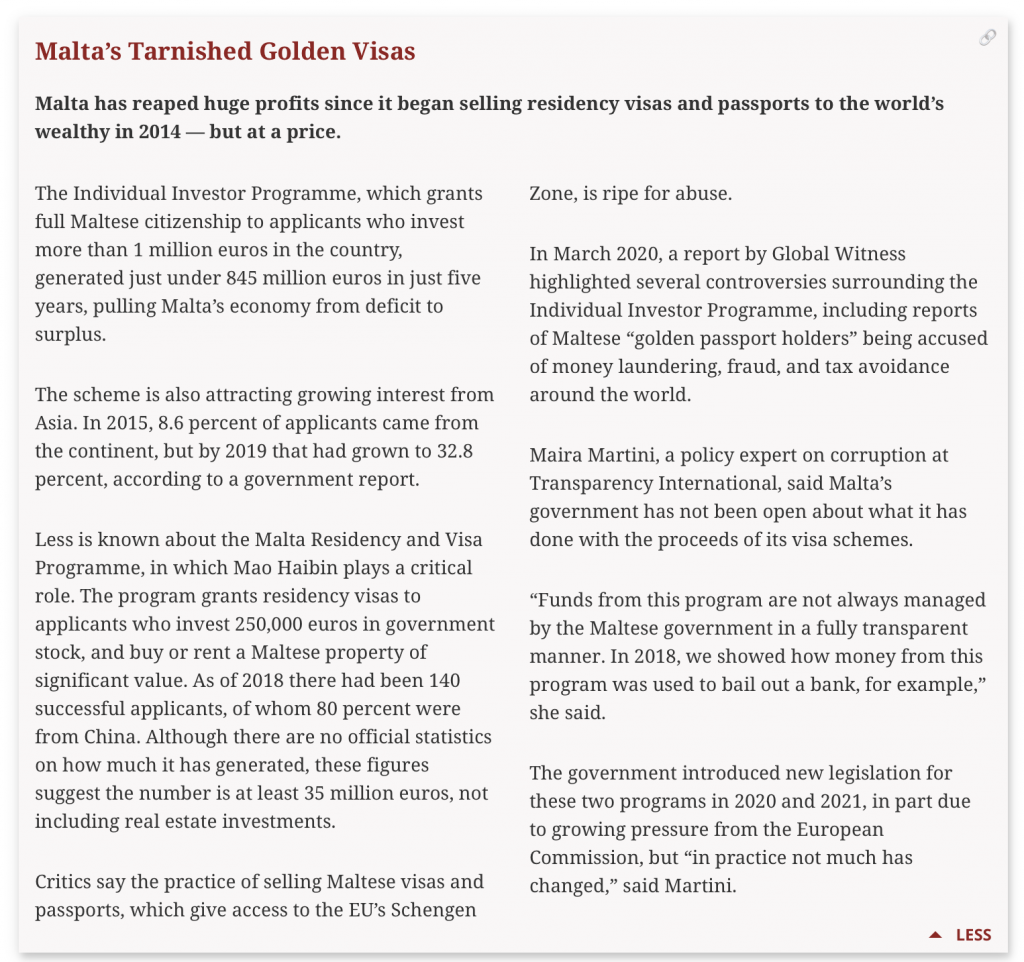

Malta has reaped huge profits since it began selling residency visas and passports to the world’s wealthy in 2014 — but at a price.

The Individual Investor Programme, which grants full Maltese citizenship to applicants who invest more than 1 million euros in the country, generated just under 845 million euros in just five years, pulling Malta’s economy from deficit to surplus.

The scheme is also attracting growing interest from Asia. In 2015, 8.6 percent of applicants came from the continent, but by 2019 that had grown to 32.8 percent, according to a government report.

Less is known about the Malta Residency and Visa Programme, in which Mao Haibin plays a critical role. The program grants residency visas to applicants who invest 250,000 euros in government stock, and buy or rent a Maltese property of significant value. As of 2018 there had been 140 successful applicants, of whom 80 percent were from China. Although there are no official statistics on how much it has generated, these figures suggest the number is at least 35 million euros, not including real estate investments.

Critics say the practice of selling Maltese visas and passports, which give access to the EU’s Schengen Zone, is ripe for abuse.

In March 2020, a report by Global Witness highlighted several controversies surrounding the Individual Investor Programme, including reports of Maltese “golden passport holders” being accused of money laundering, fraud, and tax avoidance around the world.

Maira Martini, a policy expert on corruption at Transparency International, said Malta’s government has not been open about what it has done with the proceeds of its visa schemes.

“Funds from this program are not always managed by the Maltese government in a fully transparent manner. In 2018, we showed how money from this program was used to bail out a bank, for example,” she said.

The government introduced new legislation for these two programs in 2020 and 2021, in part due to growing pressure from the European Commission, but “in practice not much has changed,” said Martini.More

Mao has several other visa and real estate ventures that target wealthy Chinese citizens looking to invest overseas, some of which overlap with his work to sell Maltese residency permits. These include Shanghai Bangyi, a visa and immigration services company, and Grandstone Investment, which offers wealth management services for Chinese nationals looking to move money abroad. Its website provides a portal for direct applications to the Malta Residence and Visa Programme.

He even co-owns a Maltese company, Asiatica Corporate Services Ltd, together with Mizzi’s personal lawyer, Aron Mifsud Bonnici, who also played a role in negotiating Enemalta’s wind farm investment.

Responding to questions, Mifsud Bonnici said he knew Mao “in his capacity as CEO of Shanghai Overseas Exit Entry Services,” and said he had processed visa applications, via official immigration schemes, in his role as a lawyer.

Mifsud Bonnici said Asiatica was opened to provide corporate services to visa applicants, but never generated any business. “Hence it never operated and is now pending liquidation,” he said. He said he knew Chen as an adviser to Shanghai Electric Power, and met him “some time into my tenure as Enemalta board secretary.”

In 2019, Mao’s younger brother, Mao Haichun, co-founded two Maltese companies with Roderick Cutajar, the former head of the Malta Residence Visa Agency, which oversees residency visa sales around the world. One of their joint ventures sells residency in Malta and other European countries to Chinese and international buyers; the other is a related real estate company.

Roderick Cutajar told reporters that the visa firm, immVest, is not linked to Mao Haibin’s Shanghai Overseas Entry Exit Service Ltd. “My relationship is strictly with immVest International,” he said. “Furthermore, rest assured that I have no relationship, personal or business, with either Aldo Cutajar, Chen Cheng or Macbridge.”

In a speech posted on Chinese video blogs in January this year, Roderick Cutajar waxed lyrical about Malta’s bid to continue attracting Chinese capital — and new citizens. He claimed to have visited China over 40 times and said business was booming.

“Our intention is to continue to grow,” he said.

Meanwhile, a world away from China, Caruana Galizia’s family is still grieving her loss, and seeking justice.

Matthew Caruana Galizia said his mother would have been gratified by the new information about the nest of companies she had been investigating.

“The new revelations confirm what she knew and had tried to make others see – that the criminal entanglement of political and business interests is a major defining problem of our time. Corruption costs lives, just as it cost my mother hers,” he said.

“I think that if she were alive to see this, she would feel a sense of relief that her work is being vindicated and that she isn’t alone in her fight.”

by Martin Young (OCCRP)