A Eurasianet commentary

The Paradise Papers comprise millions of leaked documents relating to offshore activities of the super-rich, including Queen Elizabeth II. A consortium of investigative journalists in early November started publicizing the activities and events documented in the Paradise Papers, many of which revolved around tax evasion and avoidance. Somewhat buried in the mound of data are a few nuggets of information that illustrate how kleptocratic governing systems in Eurasia operate.

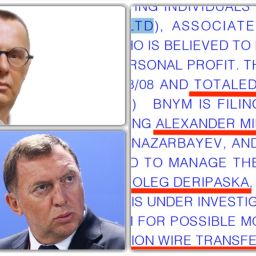

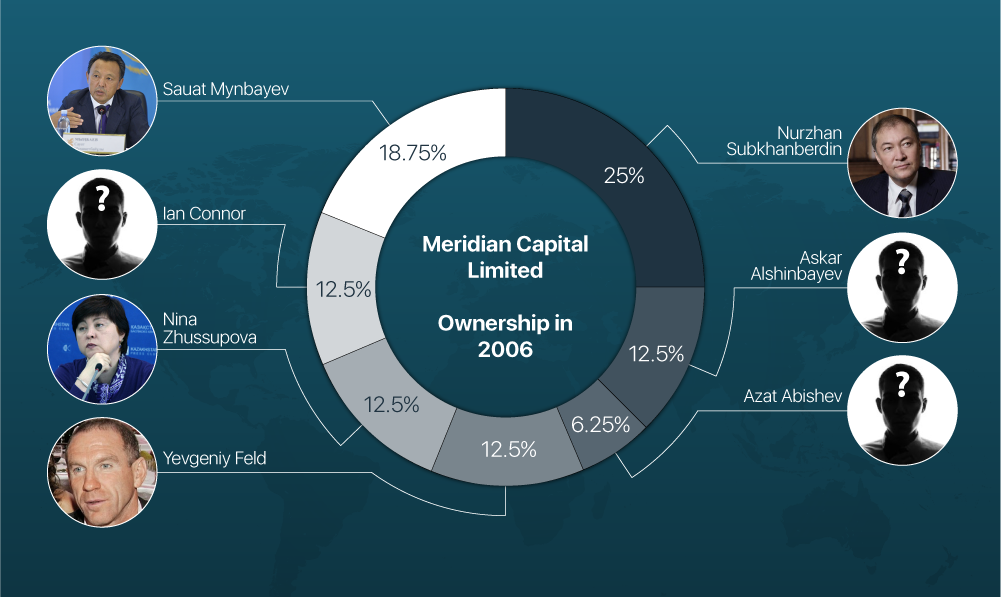

A relatively tiny batch of the Paradise Papers sheds light on a little known private company, Meridian Capital, which in 2006 controlled assets worth over an estimated $3 billion. The Paradise Papers show that Meridian’s business interests are varied: among the entities it controlled during the period in question were a dozen oil and mining fields around the world, a major Kazakh rail transportation company, a large Latvian dairy producer and a Russian regional airport company.

The leaked documents also named Sauat Mynbayev, the current chairman of Kazakh state oil and gas company KazMunaiGaz, as one of Meridan Capital’s major shareholders from at least 2006–2011, reportedly holding an 18.5 percent stake. During the timeframe in question, Mynbayev worked as the Kazakh Minister of Energy and the Minister of Oil of Gas. Research from the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) indicates that Meridian’s owners received at least $176 million in dividends out of its arrangement with a company involved in transporting Kazakh oil and minerals.

The fact that Mynbayev was profiting from oil business related to the Kazakh state while being Kazakhstan’s top oil and gas official is a clear conflict of interest – and potentially even illegal under Kazakhstani law, which states that government officials cannot “engage in entrepreneurial activities, including participation in the management of a commercial organization, regardless of its organizational and legal form.”

Since the publication of OCCRP’s research, Mynbayev has admitted that he was a Meridian shareholder, adding that he had declared this in his tax documents, and that he had given up his stake “several years ago.” In countries where the rule-of-law is strong, this revelation could easily have created a scandal. But as of this writing, there has been little reaction in Kazakhstan, and Mynbayev continues to hold his position as head of KazMunaiGaz.

Mynbayev’s involvement in a private enterprise shouldn’t really come as a shock in Kazakhstan , where the meshing of politics with business is not uncommon. It’s an arrangement that has helped maintain the political status quo in Kazakhstan under President Nursultan Nazarbayev since the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is also a system seen all over Central Asia, where repressive regimes are aided – wittingly or otherwise – by a coterie of high-powered Western lawyers, accountants, company service providers and bankers.

The list of Eurasian scandals connected to the misdeeds of the powerful is long.

For years, the anti-corruption watchdog Global Witness has highlighted how the Turkmen government maintains a multi-billion dollar off-budget fund at Deutsche Bank controlled directly by the president. The fund appears to have survived the death of president Saparmurat Niyazov, and is believed to be maintained by the incumbent, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov to this day. It’s also worth noting that Berdymukhamedov’s son, Serdar, is now an influential member of parliament while at the same time reportedly maintaining interests in a string of lucrative businesses, including a cotton-spinning plant, a mineral water factory and a chain of hotels.

Elsewhere, a few years ago in Tajikistan, money was siphoned away from the state-controlled aluminium company through a British Virgin Island company that acted as a middleman, through which $100 million went to buy two Boeing 737s to start a private airline reportedly controlled by the president’s brother-in-law.

And among the more notorious cases are that of Maxim Bakiyev — the son of the former president of Kyrgyzstan – who resided in a £3.5 million house in a leafy area of Surrey, England that apparently was bought for him by a murky Belize-based entity with funds suspected to have been stolen from the Kyrgyz state through the country’s largest bank.

There is also the case of Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of the former president of Uzbekistan. She is suspected of receiving close to $1 billion in bribes from telecoms companies, resulting in the largest forfeiture action the US Department of Justice has ever brought to recover the proceeds of bribery.

As the Paradise Papers illustrate, most of the transactions involved in these scandals were aided by law firms often registered in European jurisdictions.

In recent years, campaigners have been pushing for stricter transparency laws in an attempt to make it harder for corrupt officials to profit off the back of their countries. Earlier in the year, the United Kingdom – following similar actions in Australia and Ireland – passed legislation regarding Unexplained Wealth Orders, allowing law enforcement to investigate cases in which an individual purchases luxury items beyond their apparent means.

The UK has already brought in a new register of ‘beneficial ownership’ for companies registered in the UK (but, alas, not its Overseas Territories or Crown Dependencies), and is also attempting to bring in legislation that would reveal the real owners of all property (though progress has been slow going).

With similar moves towards beneficial ownership transparency ongoing in France, Norway, Netherlands, Ukraine and elsewhere, hopes are rising that a global beneficial ownership register may one day become a reality, thus making it harder for officials to profit from their government positions. Until that time, citizens in the countries of Eurasia will have to rely on there being more high-profile leaks to understand who really controls their nations’ wealth.

By