International institutions fail to measure up to the task of tackling globalized financial crime.

The subject of lawsuits in the United Kingdom and the United States, former Mayor of Almaty Viktor Khrapunov, his TV-anchorwoman wife Leila, and their son Ilyas stand accused of embezzlement schemes amounting to at least $300 million. Resident in Switzerland since August 2008 when they fled their native Kazakhstan to join their son — loading up a chartered plane with an alleged 18 tonnes of art, antiquities and assorted booty — the family is now the subject of ongoing proceedings by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Geneva. With a network of connections that span the globe, though, is the Khrapunov house of cards about to come crashing down, or will their friends in high places save them?

Simple, Yet Audacious Schemes

Born to a family of bureaucrats in northern Kazakhstan in 1948, Viktor Khrapunov moved to Almaty — then the country’s capital — after completing training at a college of industry and technology. Working as a mechanic while he continued with his studies, he decided to join the Komsomol (the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League), a move which marked the beginning of his political ascent. Khrapunov served as minister of energy and natural resources before being appointed mayor of Almaty, a position he held from 1997 to 2004. He went on to hold a governorship and another ministerial post, before retiring from all public positions in 2007, purportedly for “health reasons.” It is his tenure as mayor, however, from which allegations of corruption stem.Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

In August 2008, with local investigators closing in, Viktor Khrapunov and his wife hightailed it out of Almaty to the safe haven of Geneva, where their son was already resident. An investigation by the Kazakh authorities subsequently uncovered 83 shell entities that bore the family’s fingerprints.

“The theft was committed through the alienation of properties in Almaty and land in protected environmental areas,” Sergey Perov, Kazakhstan’s chief of Anti-Corruption Investigations and head of the inquiry into the Khrapunovs, told The Diplomat. “He also demanded bribes from entrepreneurs for issuing decrees of privatization, which were paid in the form of cash and real estate. We’ve uncovered 28 separate episodes of criminal activity.

“The schemes used by the Khrapunovs were simple, yet audacious,” Perov said. “The most common went like this: Mayor Khrapunov instructed his subordinates to conduct a fictitious tender for the sale of an asset to a predetermined company, the ultimate owner of which was his wife, Leila. After that, the Khrapunovs resold the object at its real value to a third party. For example, one piece of government land was bought and resold a day later at 45 times the price it was acquired for. He’s not a moral man; he even privatized a kindergarten and a hospital for veterans of the Second World War.”

As laid out by the plaintiffs in a California court case, Kindergarten No. 186 serves as an example of how the Khrapunovs allegedly conducted their business:

On or about April 16, 2001, Viktor used his position as mayor to cause public land and a building in Almaty known as Kindergarten No. 186 to be auctioned and ultimately sold to Leila’s company, KRI, for approximately $347,000… Under the laws of Kazakhstan, potential buyers of state-owned property are obligated to state how they intend to invest in and develop the property. In an attempt to make KRI’s bid appear legitimate and to ensure they won, KRI fraudulently represented that they would invest more money than their competitors (based on inside information about the competitors’ bids) in Kindergarten No. 186 and build a health center… Instead, Leila caused KRI to sell Kindergarten No. 186 to Karasha [a shell company] and three days later, Leila caused Karasha to sell Kindergarten No. 186 directly to her. The investment promise KRI used to win the bid was not passed on in the subsequent purchase agreements… [The asset] was then sold to an unrelated third party in a transaction that valued Kindergarten No. 186 at approximately $4.1 million.

It’s Good to be Swiss

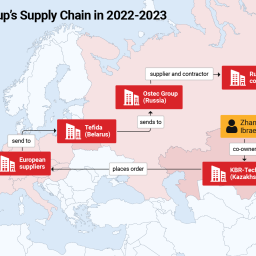

Founded at the time the family fled from Kazakhstan, the Swiss Development Group (SDG) — company slogan: “It’s Good to be Swiss” — was established as a hub of financial operations for the Khrapunovs in Geneva. Among SDG’s projects were a high-end beach resort on the shores of Lake Geneva, a mall in the city center, and a luxury ski resort, while the family also snapped up a string of other properties in Switzerland and elsewhere. As early as 2010, La Tribune de Genève ran a story raising suspicions that $10 million in capital raised for these ventures had been illegally funneled out of Almaty.

“Currently Switzerland isn’t at the top when it comes to the fight against money laundering,” Martin Hilti, executive director of Transparency International Switzerland told The Diplomat. “We have several loopholes, one being the scope of our anti-money laundering act, which is limited to financial intermediaries and doesn’t take into account other risky activities, such as the buying and selling of real estate.”

Hilti continued: “We published a report last autumn looking at the risk of money laundering in the Swiss real estate sector. It’s pretty easy to buy Swiss real estate with dirty money because of the loopholes. The main actors, such as notaries and estate agents normally don’t have any duty of due diligence or reporting. The banks have these duties, but are too far away from the business to detect money laundering.”

In 2010, the Swiss business magazine Bilan published an article naming the Khrapunovs among the wealthiest families in the country. By early 2012, however, with Viktor Khrapunov’s name added to the Interpol Red List, Swiss authorities began to take tentative steps toward freezing the family’s assets.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands — where Kazakh authorities identified 15 entities that allegedly bear the hallmarks of Khrapunov shells — in May 2017, Ilyas Khrapunov’s lawyers sought an injunction against the broadcaster Zembla, which was preparing to air a documentary examining the ties between kleptocrats and U.S. President Donald Trump.

“We approached Ilyas Khrapunov, and as soon as we told him the scope of the research and the issues we’d like to discuss with him, we got an email from his PR guy in Geneva,” Sander Rietveld, an investigative journalist and the creator of the documentary, The Dubious Friends of Donald Trump, told The Diplomat. “They warned us not to cross legal lines, but we were very transparent with him. We didn’t hear from them for a couple of weeks, and then days before the documentary was set to air, we were served with an injunction. It was Ilyas suing us.

“His main argument,” Rietveld said, “was that the research was sloppy and we were accusing him of money laundering without any grounds. The judge basically said that the research had been conducted in the correct manner, so there was no reason to block the program. It gave the documentary more publicity; it definitely backfired on them.

“It’s hard to search for the ultimate beneficial owners of entities in the Netherlands,” Rietveld said. “It’s not information that the government or the Chamber of Commerce provides in a transparent way. For example, Leila Khrapunova used to have this Dutch shell company, Helvetic Capital B.V., which was 50 percent owner of Kazbay B.V. and the other owner was Bayrock B.V. which was a shell company of Felix Sater and Tevfik Arif, the owners of Bayrock in New York.”

From Europe to the White House via Kazakhstan

It was SDG’s search for partners that led them across the Atlantic to Trump’s business partners, connecting the Khrapunovs to the inner sanctum of the current U.S. administration. In 2008, the Bayrock Group announced that it was partnering with SDG to convert the Hotel Du Parc in Montreux into “ultra-luxury” private residences. The chief operating officer of Bayrock at the time, Felix Sater, would later become the dominant force behind the company, whose offices were situated in Manhattan’s Trump Tower. Paying the Trump Organization a licence fee for the use of its name, Bayrock repeatedly partnered with the Trump Organization in trying to engineer a deal for a Trump Tower in Moscow. In 2006, Sater personally showed two of Donald Trump’s children, Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr., around the city, introducing them to movers and shakers. Daniel Ridloff also worked for Bayrock before briefly joining the Trump Organization’s acquisitions and finance arm in 2010. Articles list him as the vice president of the Swiss Development Group Investment Fund — a thinly-veiled SDG offshoot — information which he has since deleted from his LinkedIn profile.

Bayrock subsequently partnered with the Trump Organization in a failed project in Arizona financed by the FL Group of Iceland. Despite the undertaking going nowhere, Ernest Mennes, the owner of Camelback Plaza Development, who had entered into an arrangement with them, sued Bayrock in 2007, accusing Sater of threatening to “electrically shock [his] testicles, cut off [his] legs, and leave [him] dead in the trunk of his car.” The case was settled and Mennes barred from making any further comment.

The son of a Russian syndicate crime boss linked to Semyon Mogilevich, a long-term resident of the FBI’s top 10 most wanted list, Felix Sater served time in the early 1990s for stabbing a man in the face and neck with the stub of a margarita glass in a bar brawl. Upon his release, he turned to fraud, artificially inflating share prices with false information. Striking a deal to turn informant on the Russian mob, he is also said to have turned evidence on Osama Bin Laden’s network.

After leaving Bayrock in 2008, Sater was brought into the Trump Organization as a senior adviser to Donald Trump. “If he was sitting in the room right now, I really wouldn’t know what he looked like,” Trump said of Sater in a Florida court video deposition in 2013.

“Our boy can become President of the USA and we can engineer it,” Sater enthused in emails to Trump’s personal lawyer at the time, Michael Cohen. “I will get all of Putin’s team to buy in on this… we will get Donald elected.”

Sater allegedly acted as the Khrapunovs’ U.S. intermediary on $40 million of real estate and investment deals. Court documents state that he received SWIFT codes for bank transfers, $5 million of which was transferred from a now sanctioned Cyprus-based LLC to California-based Elvira Kudryashova, the Khrapunovs’ daughter, to purchase three condos in Trump SoHo, a project developed by Bayrock in partnership with the Trump Organization. The units were purchased by three shell companies established in April 2013 and dissolved shortly after they were sold. Financing to the tune of $50 million for Trump SoHo and three other Bayrock projects flowed from the FL Group, an Icelandic private equity company named in the Panama Papers with significant ties to dirty money from the CIS.

The law firm Bracewell and Giuliani was hired by Bayrock to create offshore companies to minimize taxes. Now attorney to Donald Trump, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s firm had an office in Kazakhstan, with Giuliani raising funds there for his failed 2008 presidential bid. It was on the advice of Bracewell and Giuliani regarding tax structures that in 2007, the Khrapunovs together with the Bayrock Group set up KazBay B.V. in the Netherlands.

In 2016, Nicolas Bourg, former director of Triadou SPV S. A. testified that the Khrapunovs had ordered him to move money out of the United States after a California lawsuit was filed against them. “Triadou is a shell entity for SDG and has no corporate presence separate from SDG,” he said in the New York Southern District Court. “Monthly meetings occurred in Geneva between myself, Ilyas Khrapunov, Peter Sztyk (an advisor of Ilyas), and, at times, my longtime business partner, Laurent Foucher. The agenda at each meeting was to discuss the investments of the Ablyazov-Khrapunov family money (i.e., not only money invested through SDG or Triadou.) At these meetings, I frequently received directions from Ilyas regarding various business ventures, including Triadou and others that the Ablyazov-Khrapunov family money was involved in.”

Bourg went on to testify that the Khrapunovs commingled funds in their U.S. dealings with Mukhtar Ablyazov, a kleptocrat and former energy minister of Kazakhstan. Subject to asset-freezing orders amounting to $4.9 billion in the British courts alone, Ablyazov stands accused of having embezzled up to $10 billion, largely from BTA, the Kazakh bank he once chaired. Ilyas Khrapunov is married to Ablyazov’s daughter, Madina, and court judgments hold him responsible for a swathe of his father-in-law’s financial affairs.

One of multiple Bayrock projects partly financed by the FL Group was a Florida development which ended in ignominy with condo buyers suing for $7.8 million. Former Bayrock partner Jody Kriss filed a suit which named Sater, alleging that Bayrock was “substantially and covertly mob-owned and operated.” After eight years in the U.S. courts, in February 2018 the case was the subject of a sealed settlement.

“Felix Sater was involved in laundering money for the Khrapunovs,” James S. Henry, an investigative reporter, lawyer, and expert on tax evasion told The Diplomat. “That started roughly when Viktor Khrapunov left Almaty and fled to Geneva and continued on probably even as late as 2015. Sater is up to his eyeballs in financial chicanery. The fact that they cut him all these deals,” Henry says “allowed him to move onto a life of financial fraud and to raise money from banks and regular investors as well as from people like the FL Group without letting anyone know that he was a twice-convicted felon.

“The FL Group had a $2 billion plan that they’d talked about [with Bayrock]. A lot of this never got funded, but Bayrock received about $50 million in equity. It’s hard to account for why they were investing there,” Henry contends. “I spent a lot of time in Iceland working on the Panama Papers. The question was, who was the FL Group and why were they investing in Bayrock? The FL Group was this private equity firm with upstream ties to people who had interests in Russia. The Iceland Central Bank never really audited the connections, so when the banks failed in 2008, there was no information available on who had accounts in the private banking arms of key banks. There were several of them which had big investments in the FL Group. There was also this strange moment in fall of 2008 when Putin showed up just as Iceland was going into financial crisis and offered a very generous loan to Iceland to bail them out. They actually dispatched a whole team to Moscow to check this out. For about six weeks, they were negotiating an alternative to the IMF. Why was Putin bailing out Iceland? Well, there were some big Russians who had money in the banks and I think we still don’t know much about what their names were.

“There were stories about Alfabank being an investor, as well as Alisher Usmanov, whose wife introduced Putin to his girlfriend. Usmanov is an oligarch who in September 2008 was on the verge of getting a huge loan from one of the Icelandic banks,” Henry says. “It was a very odd transaction for this oligarch to be getting. I think in terms of conspiracies, the FL Group is a smoldering fire that just can’t be put out. Overall, though, given what’s happened in court cases in Europe and the U.S., it’s hard to make any of these jurisdictions look like a winner when it comes to prosecutions. It’s an example of how weak the international instruments are when it comes to tracking down these kinds of financial crimes.”

As of January 2018, Triadou’s lawyers have issued a motion to stay with regards to Sater, indicating that he is now ready to cooperate with discovery requests. In March 2018, Viktor and Ilyas lost a New York court case for violating a confidentiality order. “The court noted that Ilyas Khrapunov has played games with the court in the past and cited, as one example, the fact that the Khrapunovs requested to appear at the evidentiary hearing by phone but later retracted that offer, claiming that it would violate Swiss law to testify at the hearing while residing in Switzerland,” wrote U.S. Magistrate Katharine Parker. The court ordered the Khrapunovs to pay BTA Bank and the City of Almaty’s legal fees, noting that their defense that they had not leaked evidence was “not credible.”

Aristocratic Acquaintances

Meanwhile, in the U.K., a story about how this all ties to the British aristocracy continues to fly under the radar. Formed as a private company in 2010, New World Oil and Gas (NWOG) went public in 2011 using the exchange unregulated fund regime, part of Jersey’s race to the bottom in terms of regulation. The founding director of NWOG, Ilyas Khrapunov’s advisor Peter Sztyk, was married to Mukhtar Ablyazov’s alleged mistress, Bota Jardemalie, at the time of the company’s incorporation. Jardemalie is wanted by Kazakhstan for her part in embezzlement from BTA Bank.

In August 2013, after NWOG had disappointing drilling results, a company called Niel Petroleum, whose director and largest shareholder were the Khrapunovs’ erstwhile business partners Nicolas Bourg and Laurent Foucher, offered to buy out NWOG. The driving force behind numerous dubious projects across Central Africa, the Niel Group is named as an “Ablyazov-Khrapunov controlled entity” on legal documents. Sztyk was eventually forced off the board of NWOG after being outed as a money launderer by Bourg in 2016.

Control over the regulation of NWOG on the London Stock Exchange was delegated to Beaumont Cornish, meaning that the compliance officer for NWOG, until it was effectively thrown off the stock exchange in late 2016, was Felicity Geidt. The sister of the Queen’s former personal secretary, Felicity Geidt has been FCA regulated for a series of oversights since 2001.

Having been first appointed to the royal household when the Duke of York left the Royal Navy, Christopher Geidt rose through the private office to become the Queen’s private secretary before being ousted in July 2017. This is the same Duke of York, of course, that Mukhtar Ablyazov once threatened to call as a witness in his defense. For his loyal service, Geidt has since been elevated to the House of Lords, becoming part of the legislature.

Another piece in this series of opaque connections saw Robert Hankes appointed to work as a project manager for NWOG in 2011. His brother, Sir Claude Hankes — the man brought in by the Iraqi government to conduct an investigation into the UN oil-for-food scandal — is an extremely close friend of the Duke of Edinburgh. Sir Claude Hankes is the only honorary fellow and life member of the St. George’s House Council at the House of Windsor.

The Wheels of Justice

So, is time running out for the Khrapunovs or will their connections save them? In the latest legal episode under British jurisdiction, on March 21, 2018, the U.K. Supreme Court dismissed Ilyas’ appeal against a previous ruling with regards to breaches of freezing orders on his father-in-law’s assets and contempt of court. Finding that his actions constituted “the tort of conspiracy,” the judges also dismissed Ilyas’ argument that the British courts lacked jurisdiction over him.

That Ilyas Khrapunov acted as an accomplice to Ablyazov’s embezzlement schemes, the ongoing U.K. lawsuit has left “no grounds for doubt,” according to a representative of BTA Bank. “[…T]he Commercial Court of England and Wales issued a decision obliging Ilyas Khrapunov to provide all data under a previously imposed disclosure order… information about his assets and the assets that he manages on behalf of Mukhtar Ablyazov, but he refused to do so,” the representative told The Diplomat.

Back in Switzerland, Ilyas and his wife hold diplomatic posts representing the Central African Republic at the U.N. Mission in Geneva as a means to travel freely, but the mission, located in an otherwise residential block on the outskirts, appears rarely if ever to be staffed. At 3 Mont Blanc, a prestigious property in the city center, once a key Khrapunov asset, with the SDG long since having been sold off and in liquidation as of January 2018, the company’s plaque has been removed. Similarly, another shell, Swiss TV S.A., has disappeared from Rue Philippe-Plantamour.

Henri Della Casa, spokesman at the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Geneva, would only confirm that “Proceedings against the Khrapunovs by the Prosecutor’s Office in Geneva on suspicion of money laundering are still ongoing. Due to the investigation, the Public Ministry will not comment further at this stage.” At the time of writing, the Federal Office of Justice in Switzerland had yet to respond to a request for an update as regards an extradition request made by Ukraine for Ilyas Khrapunov, although a source who spoke on condition of anonymity told The Diplomat it had been “kicked into the long grass.”

For the Kazakh authorities, though, having failed with this route in the past, it’s no longer about extradition. “Currently, we’re not desperately looking to [extradite them],” Perov, the head of the Kazakh inquiry into the Khrapunovs, told The Diplomat. “We have solid proof that they funneled stolen funds abroad, mainly to Switzerland and then began to launder it. All the evidence we’ve collected was transmitted to the Swiss authorities and the City of Almaty has initiated civil proceedings against the Khrapunovs in the U.S. We’re ready to pass our evidence to any country which might decide to prosecute them.”

The Khrapunovs continue to claim that cases against them are the result of political persecution. At the time of going to press, Khrapunov family lawyers had not responded to requests for comment.

By Stephen M. Bland

Stephen M. Bland is a freelance journalist and author specializing on Central Asia and the Caucasus.