In 2019, OCCRP reporters started looking into the theft in Spain of a luxury watch owned by Rashad Abdullayev, the son of the former head of Azerbaijan’s notoriously corrupt state oil company.

That incident eventually led to the discovery that Rashad secretly owned a $22-million flat in London.

Recent U.K. legislation made the revelation possible — with a little help from OCCRP’s data team.

U.K. properties are often owned through companies set up in tax havens that anonymize corporate ownership, opening a neat loophole that has allowed people to hide their tracks — and ownership.

But in 2022, the U.K. created a registry requiring offshore firms to declare that they own property in the country.

“New transparency rules are starting to unveil how the world’s political leaders, including those from countries with serious governance issues, own vast amounts of U.K. real estate via once secretive offshore companies,” Julie Swann, of Transparency International U.K., previously told OCCRP reporters.

There’s just one problem: Members of the public can only search the registry by company name — not by the name of the person behind the company.

That’s where OCCRP’s data desk came in.

Dataset Remix

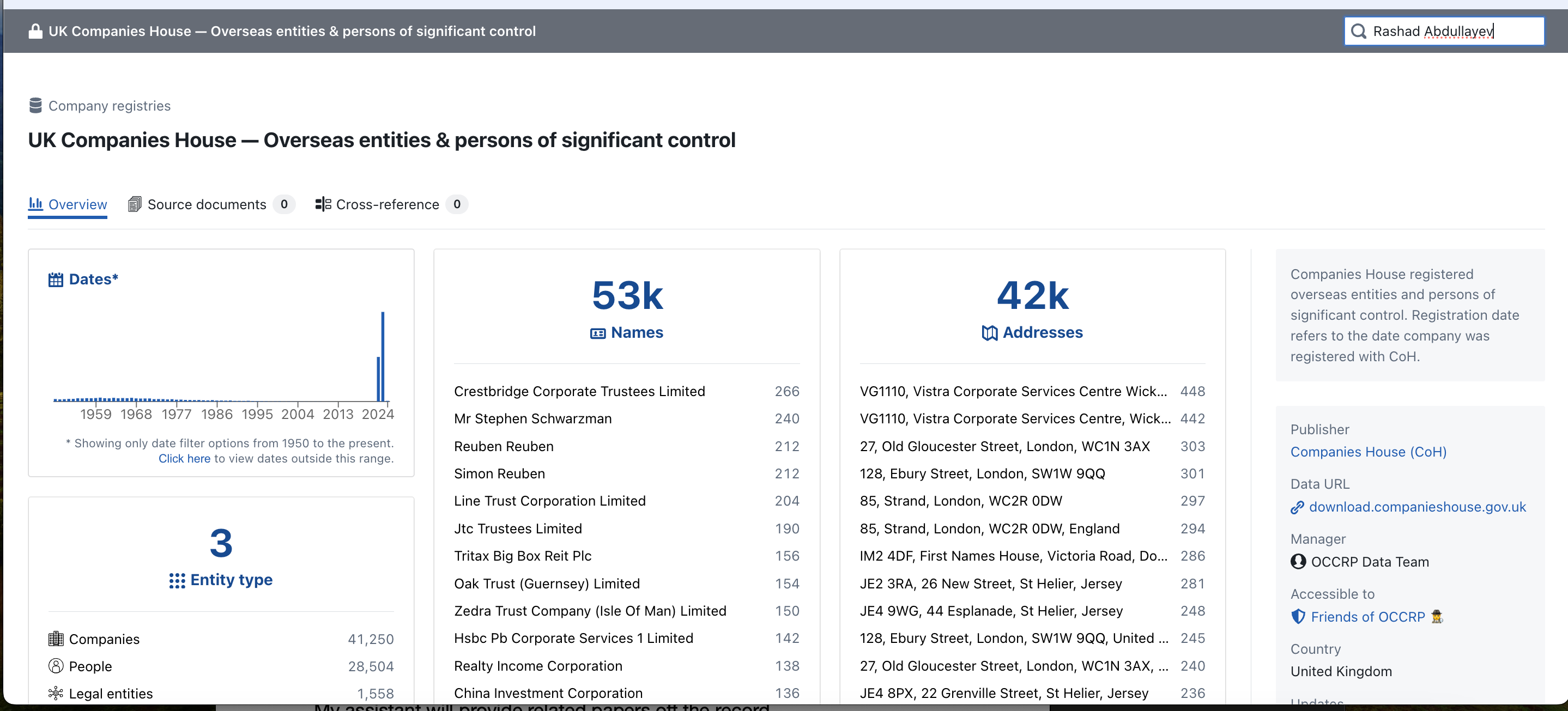

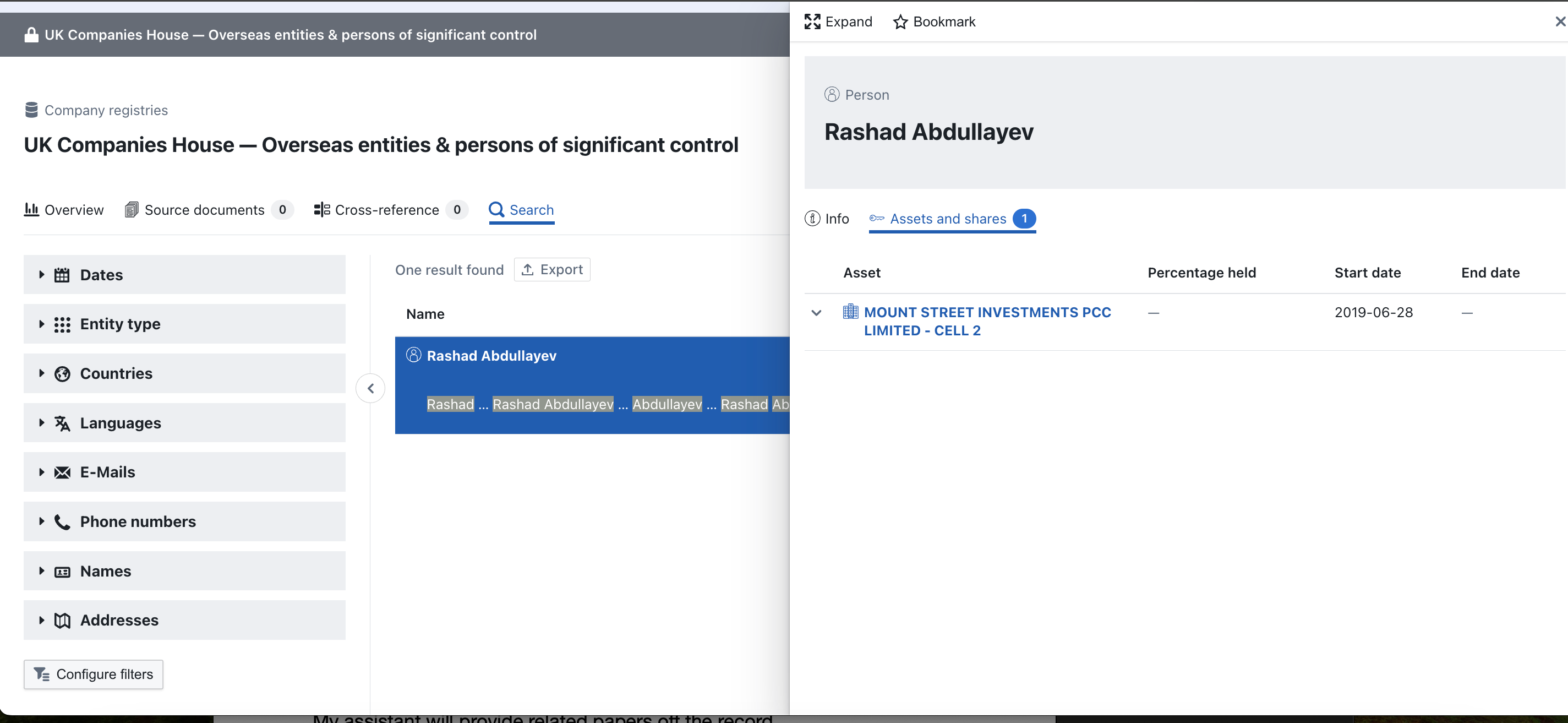

Our team took advantage of a little-known function on the registry, which allows a user to download the entire “overseas entity” dataset and search for owners from specific jurisdictions. This information was uploaded into Aleph, OCCRP’s data platform, to cross-reference with other datasets.

And while the U.K.’s registry does not allow a journalist to search the data by owner’s name, Aleph does.

But another problem then arose for journalists — appearing in the U.K. overseas entity data means that entity owns property in the U.K., but it doesn’t tell you which property it owns.

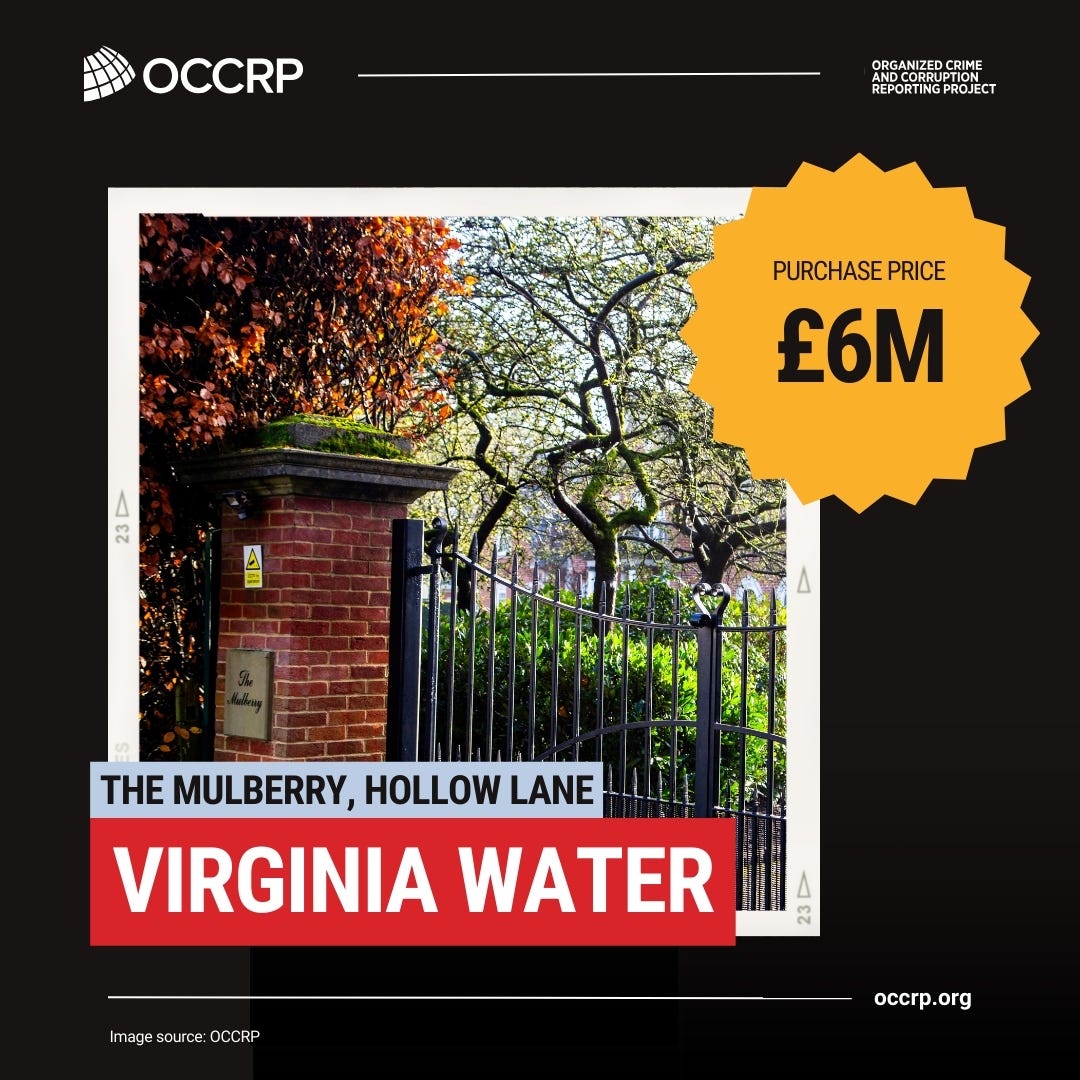

So, the team scraped data from another source — the British land registry of overseas companies owning property in England and Wales. Combined, these two datasets allow journalists to see both the beneficial owner of a foreign company that holds property, and where the real estate is located.

Which brings us back to the ultra-pricey Richard Mille watch — one of just 75 such pieces in existence — which was stolen in Ibiza in 2019.

Azerbaijani media had been reporting that the watch belonged to Rashad, but there was no confirmation until OCCRP managed to obtain a police report from Ibiza, which named him.

OCCRP published a story identifying Rashad as the watch’s owner, and noting that he was the son of Rovnag Abdullayev, then president of the state-run energy giant SOCAR.

Journalists had long investigated alleged corruption within SOCAR, such as efforts by two of the company’s subsidiaries to siphon $1.7 billion from a major gas project, and on apparent plots to enrich insiders, including Rovnag Abdullayev’s father-in-law.

But until the stolen watch incident, they hadn’t thought to look into Rovnag’s son, said OCCRP journalist Kelly Bloss.

“It was a hint that this guy has a lot of money,” she said.

Bloss had been working alongside Transparency International U.K. to track assets owned in Britain by politically exposed persons from Azerbaijan.

They plugged Rashad’s name into the data, and there he was: the owner of a flat in one of London’s most expensive areas, at the age of just 28.

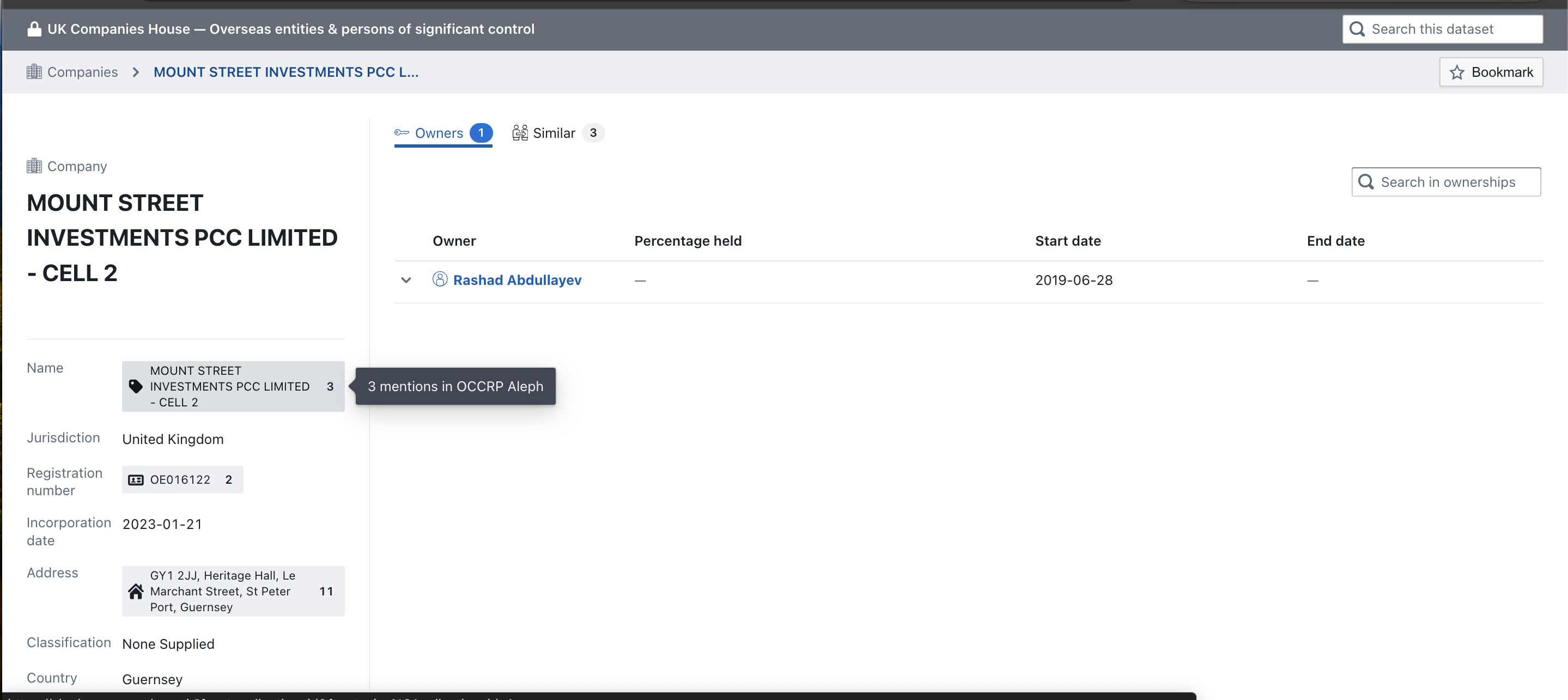

Rashad had acquired the property through a company registered in Guernsey, a British dependency in the Channel Islands that is famous for its corporate secrecy.

OCCRP published an investigation revealing this in January 2023, the year after Rashad’s father was removed from his position as head of SOCAR.

It was a major breakthrough, said Bloss.

“We found Abdullayev family property outside Azerbaijan for the first time,” she said. “We knew they were rich, but we didn’t know where they were hiding their property.”

Rashad’s father, Rovnag, told OCCRP at the time that he had made no payments in relation to his son’s apartment, and knew nothing about the origins of the money used to buy it.

Rashad did not reply to questions from OCCRP, but public information shows he worked for a SOCAR-affiliated company when he was 16 years old. Three years later he founded a real estate company in Turkey, where he also owned a restaurant. And he co-owned a chain of gas stations in neighboring Georgia.

While mysteries remain about how Rashad got the money to buy the London flat, the discovery of the property did highlight his well-connected family’s wealth.

Another recently published story also used the dataset to discover previously unreported properties belonging to the family of Armenia’s ex-president.

And the reporting couldn’t have been done without the U.K.’s efforts to improve transparency in its real estate sector — however flawed they may be.

Transparency International’s U.K. chapter is urging the government to close “loopholes” in the registry, including by “preventing people from submitting misleading information without consequence.”

“While the new register is proving its worth, it is far too easy to evade and avoid the new rules,” said Swann.

Original article source: OCCRP

Published in

Feb 8, 2024