Despite public denials, well-known citizenship broker Henley & Partners helped disgraced financier Jho Low, who stands accused of stealing billions from Malaysian sovereign wealth fund 1MDB, obtain a passport from Cyprus.

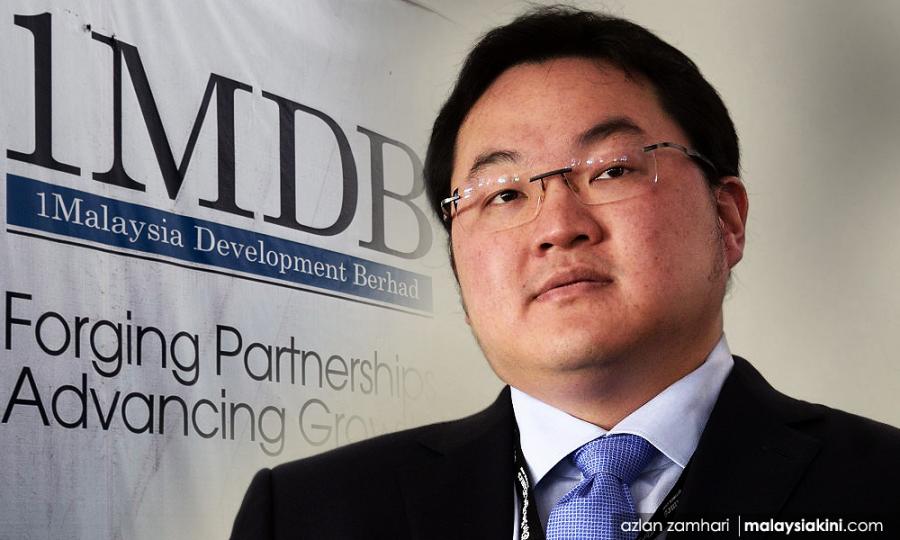

Jho Taek Low had billions of dollars, but he was running out of places to put them.

By 2015, the Malaysian financier had become the face of the now-infamous 1MDB embezzlement scandal. His theft of billions from Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund had been widely reported. So had the trail of splashy purchases he made around the world: a transparent grand piano for supermodel Miranda Kerr, a New York City penthouse once owned by Jay‑Z, a $6‑million emerald green soup can painted by Andy Warhol, an entire hotel in Beverly Hills.

Banks were increasingly wary of him. So were governments. He was under investigation by law enforcement in Singapore and Switzerland. U.S. authorities were closing in, too. He needed a safe refuge for both himself and his money.

To solve these problems, Low turned to the sunny eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where, with a view to establishing a new financial foothold, he purchased citizenship in 2015 under the country’s controversial “golden passport” scheme.

Technically known as Citizenship By Investment, the program was meant to attract wealthy foreigners seeking European Union passports. But in the eyes of critics, its main effect was to make Cyprus a go-to destination for kleptocrats and criminals who want to pay their way into the bloc. It also proved lucrative for a small army of lawyers and financial service providers who greased the wheels.

The program was ditched last October after a damning investigation by Al Jazeera exposed local politicians offering to help a fictitious Chinese criminal get citizenship. The circumstances under which Low received his golden passport are under scrutiny by Cypriot authorities.

Now, an investigation by OCCRP and the Sarawak Report can reveal previously undisclosed details about how Low obtained Cypriot citizenship — and who helped him do it.

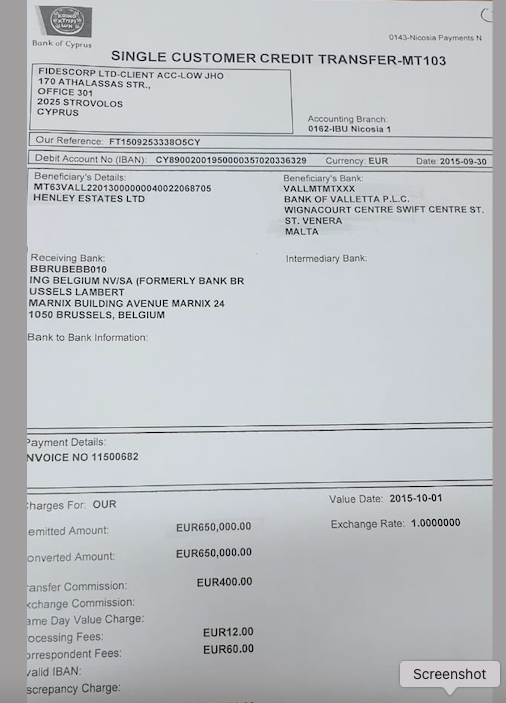

The company has repeatedly denied helping Low, while blaming local employees for any mistakes that were made. But invoices and other documents obtained by OCCRP show that Henley pocketed at least 710,000 euros for services it provided to him. The bulk of its earnings came from a 650,000-euro commission Low paid for his purchase of a luxury seaside villa.

Acquiring local real estate worth at least half a million euros was a requirement of the Cypriot visa program. This provided opportunities for citizenship firms like Henley to pad their earnings by serving the additional role of a real estate broker.

Some of the assets Low purchased with allegedly stolen funds. From top: The “Tranquility” yacht, a painting by Claude Monet, and a hotel in Beverly Hills.

“In any major scandal there’s always a multitude of enablers that allow the movement of the money, and in doing so they allow the fraud to continue,” said Debra LaPrevotte, a former FBI special agent who was involved in the initial stages of the 1MDB investigation.

“Every single one of those people has some type of due diligence responsibility. Yet they ignore it, and by enabling the movement of this money they don’t see the secondary effect of this, that the billions that left Malaysia should have been helping the people of Malaysia.”

A “Staggering” Amount of Stolen Money

In July 2016, the U.S. Justice Department filed a complaint alleging that over $3.5 billion had been misappropriated from 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a fund created by the government of Malaysia to promote economic development, between 2009 and 2015. (That figure would later be revised upwards to $4.5 billion.) The money was stolen by high-level fund officials and their associates, then laundered through a series of complex transactions and fraudulent shell companies with bank accounts in Singapore, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and the United States.

The complaint named Low as the mastermind behind the theft. He was accused of laundering more than $400 million that had been diverted from the fund. Much of it ended up in the U.S. in the form of luxury real estate, jewelry, and iconic artworks, including a Monet and a Van Gogh. Stolen 1MDB money was also spent on gifts for some of Low’s famous friends, including Leonardo DiCaprio — who received the Oscar statuette Marlon Brando had won for “On The Waterfront.” Some of the money was also allegedly used to fund the production of “The Wolf of Wall Street.”

Low has denied any wrongdoing in the 1MDB affair, insisting he was just an intermediary and that the charges against him are politically motivated. His whereabouts are unknown, and two law firms representing him in the U.S. and U.K. did not respond to requests for comment.

Credit: Sadiq Asyraf/AP Protesters hold placards reading “Save Malaysia, Arrest the Thief” during a protest in Kuala Lumpur calling for the arrest of Jho Low.

Serving the Global Elite

In the world of citizenship for sale, service providers are key. These companies identify target nations, manage the required investments, and do everything else needed to help the world’s wealthiest people become “global citizens,” as their marketing language tends to phrase it.

And there is no service provider more sought after than Henley & Partners, a London-based consultancy that bills itself as “the global leader in residence and citizenship planning.”

While Henley boasts of its exclusive client list and high-level connections, it has emphatically denied any connection with Low. In November 2019, the company released a statement rejecting media reports that it had helped the Malaysian fugitive.

But documents obtained by OCCRP indicate that Henley did, in fact, play a role in brokering Low’s Cypriot citizenship –– and that it received a hefty commission for its services.

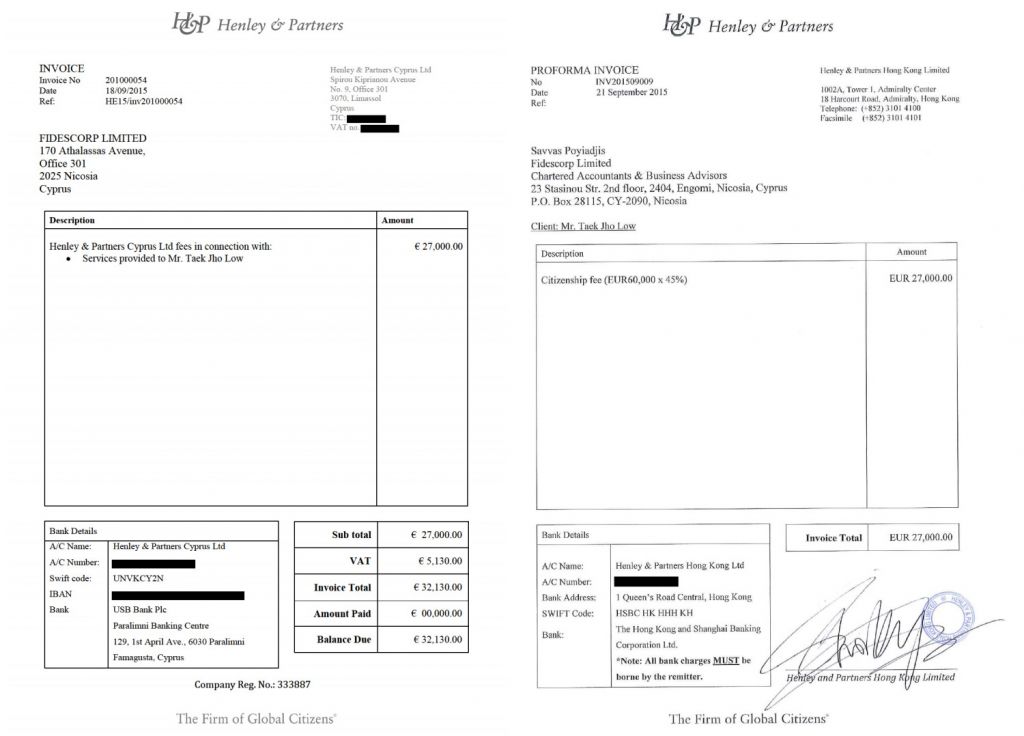

Low signed a contract with Henley on May 7, 2015, according to a copy of the document obtained by OCCRP. By that time, he was already emerging in the public eye as a key player in the 1MDB saga.The first section of the client agreement between Henley & Partners and Jho Low, signed on May 7, 2015. (Click to see more.)

Less than four months later, he had a Cypriot passport in his hands after purchasing a 5‑million-euro beachfront villa from a real estate firm partnered with Henley.

In a series of emails, Henley & Partners told OCCRP that it had rejected Low as a client “due to the contents of an external due diligence report that made it clear that he was a second-generation PEP [politically exposed person].”

“To be very clear, Jho Low was never a client of Henley & Partners,” the firm said in a three-page statement. “Henley & Partners was not mandated by Jho Low.”

The company continued to deny any relationship even after being presented with documentary evidence. “We can however understand a level of confusion from outside observers as to the nature of the relationship,” a spokesperson wrote.

Henley & Partners said that after rejecting Low, it referred him to FidesCorp Services Limited, a Cyprus-based accounting firm that also provides citizenship services. Henley & Partners wrote that it had “no interest” in FidesCorp and had an “ad hoc relationship” with the company, which it said provided “complementary and non-competitive services to a similar client base.”

In fact, the two companies have worked closely together for years, with the head of FidesCorp even helping Henley set up its Cyprus office.

Leaked emails and financial documents obtained by OCCRP indicate that FidesCorp played a role in arranging Low’s Cypriot affairs, but that the relationship with Low was initiated and led by Henley & Partners.

In this way, Henley appears to have used FidesCorp as a shield to avoid scrutiny over its relationship with Low, even as it earned hundreds of thousands of euros on commissions related to his purchase of a Cypriot passport, the documents show.

They also show that Henley & Partners worked with Low until at least late November 2016, by which time his close ties to the 1MDB fraud were widely known.

Due Diligence Done?

Service providers such as Henley & Partners have a legal obligation to look into their clients’ backgrounds to make sure they are not facilitating money laundering.

If a client appears to be a PEP, or politically exposed person, they are supposed to be examined with even more scrutiny, since they’re at higher risk of being involved in corruption. The rules also apply to real estate agents.

In Low’s case, it would not have taken long to uncover troubling information about his wealth.

“As of February 2015 there was publicly available information and media articles connecting Jho Low with the 1MDB scandal,” LaPrevotte, the former FBI agent, told OCCRP. “Anybody doing any due diligence should have seen them.”

Henley & Partners did see them. The contract it signed with Low contains an attached profile from World-Check, a commercial database of high-risk individuals. The profile correctly identifies Low as a PEP for being a “close associate” of Najib Razak, Malaysia’s prime minister at the time, who has since been sentenced to jail for sending 1MDB funds to his personal bank accounts.

In the document, Low is described as the Chief Executive Officer of Jynwel Capital Limited, the Hong Kong financial services firm the U.S. Department of Justice says funneled money stolen from 1MDB.

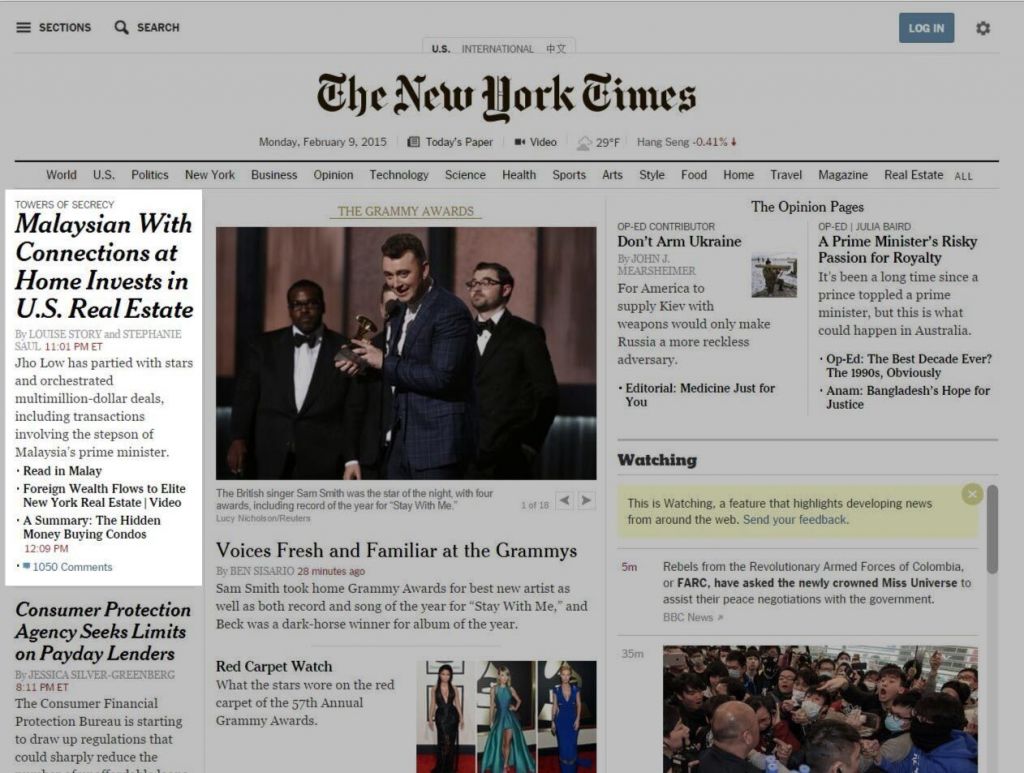

One lengthy New York Times investigation cited in the profile detailed extensive concerns about Low’s lavish spending and opaque real estate deals, given his close ties to Razak.

“Speculation is brewing over where Low is getting his money from,” it quoted another news outlet as saying.

Maira Martini, a policy expert at Transparency International, said that if Henley saw Low as too high-risk for its citizenship brokering business, it should have avoided working on his behalf as a real estate broker, too.

“Did they also take into account the level of risk when supporting him to find a property in Cyprus?” she asked.

Leaked emails obtained by OCCRP show the company’s own employees actively working to help Low obtain citizenship.

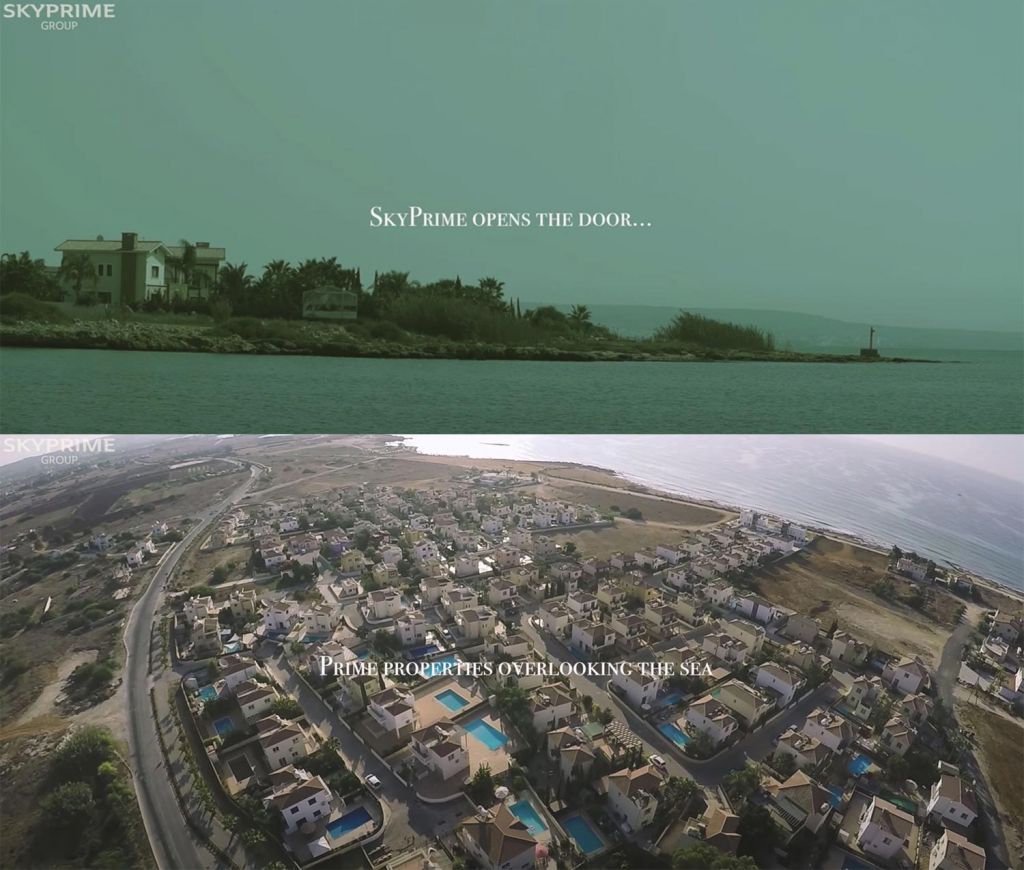

In order to qualify, Low chose to pay a local developer $5 million euros to build him a villa on a prime plot of beachfront land in Ayia Napa, an eastern Cyprus resort town whose white-sand beaches and turquoise waters made it a prime destination for investors seeking passports.

In an email to Low on June 21, 2015, Yiannos Trisokkas, at the time Henley & Partners’ managing partner in Cyprus and chairman of the firm’s real estate committee, outlined the next steps.

“We have already instructed our exclusive local service provider and the companies are ready with the nominee services included as well,” he wrote. “Once the contract of sale is signed for the villa between the seller and the buyer (your company), then the nominee will be signing further to your written instructions.”

Trisokkas instructed Low to transfer 5,960,000 euros for the house to an escrow account in Cyprus that had been set up for him by FidesCorp on instructions by Henley & Partners

That amount, he noted, did not include what Low would need to pay for “anything related to your citizenship application.” He asked Jennifer Lai, Henley’s head of business at the time, whether she had invoiced Low for the application.

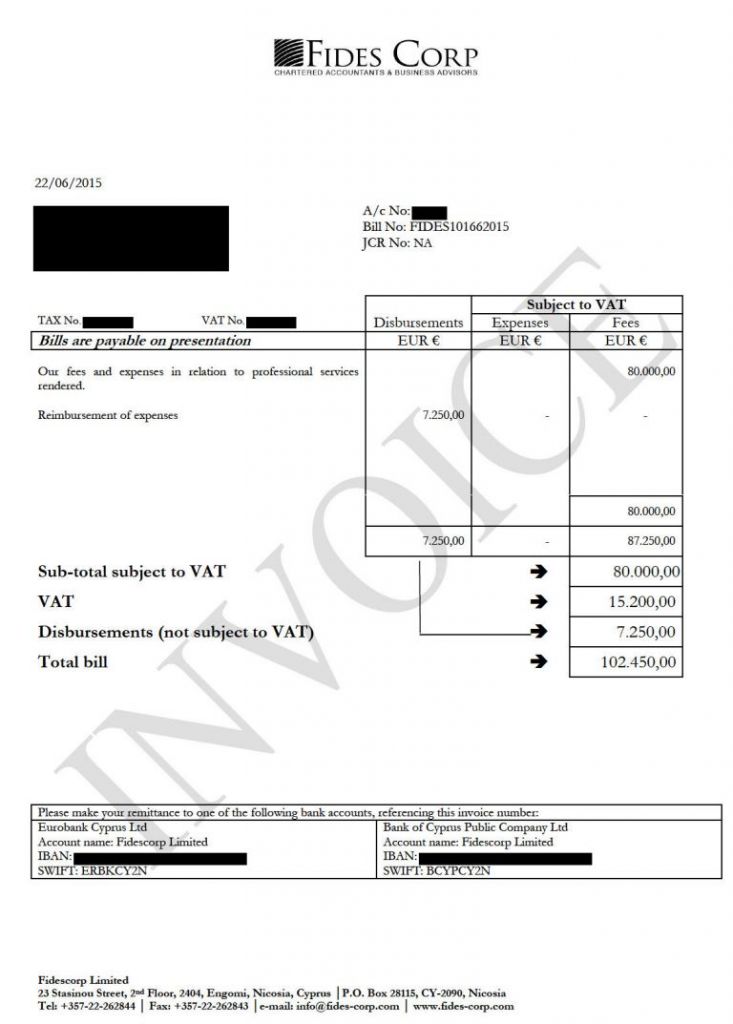

The next day, on June 22, FidesCorp invoiced Low 80,000 euros for “our fees and expenses in relation to professional services rendered.” Out of this sum, 60,000 euros were then sent to Henley — a payment the company described as a referral fee.

“Due to long standing contracts that were then in place, but are now amended, H&P was in the position to invoice Fidescorp for commission payment for the referral,” the company said.

Three days after Trisokkas’s June email, 5,960,000 euros were transferred from Low’s personal account at the Abu Dhabi State Fund-owned Falcon Private Bank to the client escrow account at Bank of Cyprus set up by FidesCorp, according to a report drafted by a Cypriot government investigative committee.

According to the report, Deutsche Bank acted as a correspondent bank in the transaction. A Deutsche Bank spokesperson said that “for legal reasons we cannot provide any information on potential or existing client relationships.” The Bank of Cyprus did not respond to a request for comment.

Henley’s assistance to Low did not stop there. Leaked emails show that in late November 2016, Low changed his mind about the purchase. He emailed Trisokkas to say he wanted to build his house on a larger plot than the one he initially acquired.

Trisokkas swiftly replied, offering a bigger beachfront plot in the same area that would have “more privacy,” before agreeing to scrap the old contract and sign a new one “under the same terms and conditions.” A new purchase agreement was signed seven months later, in June 2017.

“We remain entirely certain that this firm did nothing wrong,” Henley wrote in a statement to OCCRP, underlining the words for emphasis.

However, it admitted, “It may be that some individual staff members involved at the time did not act as one team or failed to adhere to the new procedures or did not exercise a sufficient level of judgment as to their interaction with real estate partners.”

The firm added that “all possibly involved and responsible persons are no longer with the firm today,” including Jennifer Lai and Yiannos Trisokkas.

“Henley and Partners in 2021 is not the Henley [and] Partners of 2010, or of 2015–17,” the company said. “There has been a series of significant changes both in terms of senior management and in terms of governance, structure and processes.”

Indeed, according to her LinkedIn profile, Lai left the company in September 2020, after spending nearly five years as a managing partner.

However, as of mid-January 2021, Trisokkas was still a director of Henley & Partners Cyprus Limited, according to corporate documents. His profile was removed from Henley’s website in early January, shortly after OCCRP sent Henley an email inquiring about its role in brokering Low’s citizenship.

FidesCorp declined to comment, citing client confidentiality. “In light of the fact that an investigation is currently in progress by the authorities of the Republic of Cyprus, we are obliged to refrain from making any statements,” the firm added.

A view of Valletta in Malta, where a Henley & Partners subsidiary helped broker real estate deals for clients seeking citizenship in Cyprus.

A Mysterious Intermediary

The bulk of Henley & Partners’ earnings from Low came not from the “citizenship fee” he paid, but from a large commission a Henley subsidiary charged him on his purchase of the waterfront property.

This commission — 650,000 euros, or an unusually high 13 percent of the property’s sales price — was paid to Henley Estates Limited, a Maltese company that had been set up in 2010 by Andrew Taylor, a broker who worked with Henley on real estate deals for citizenship services. He was later hired, and by 2015 the company had been fully integrated into Henley & Partners.

On his LinkedIn page, Taylor listed himself as Henley & Partners’ vice-chairman until early January, when he removed the title shortly after OCCRP submitted questions to Henley & Partners about the Low deal.

Henley & Partners told OCCRP that because Henley Estates had started out as an independent company set up by Taylor, it had retained some of its old contacts and business practices. Henley Estates sometimes received payments for its work brokering property deals for local developers, but had never been paid by Low, the company said.

“Any engagement between Jho Low and H&P staff, if any, was a result of Henley’s long-standing position as an agent of multiple real estate developers,” the company wrote.

“At no point did any person or entity within the H&P Group structure, including Henley Estates, ever contract or receive income directly from Jho Low. They contracted and received income from long standing corporate and real estate partners.”

However, OCCRP has found that this is incorrect. According to a transfer receipt obtained by reporters, Low himself paid the 650,000-euro fee directly to Henley Estates, from the account in Cyprus set up for him by FidesCorp.

The deal was shrouded in secrecy and conducted with the help of multiple shell companies and nominee service providers — firms that offer “nominees” to act on behalf of other companies, to keep their true owners hidden.

In short, the villa was sold by SkyPrime, a local real-estate developer with high-level connections, and a longtime partner of Henley in Cyprus. It advertises itself as catering to “high net worth individuals.”

However, parts of the transaction were processed through a shell company called Donnica Management Limited, which has no website or public presence and was registered in May 2015, the same month Low inked his contract with Henley. The company appears to have been set up for the sole purpose of facilitating the deal — and obscuring any connection to Low. It was Donnica, not SkyPrime, that received Low’s payment for the villa. And it was Donnica, not Low, that was invoiced by Henley & Partners for its commission fee.

Donnica and SkyPrime appear to be connected, since they have the same address, directors, and ultimate shareholder. But both companies have hidden their true owners behind a nominee service provider.

Nominees fill corporate posts to keep the true owners of companies secret. In this case, the nominee service provider concealing the owners of both Donnica and SkyPrime was run by a partner in the Cypriot law firm Tsitsios & Associates.

The law firm declined to comment on the Low case, but it has worked with Henley before, according to this internet post written by one of its associates, which boasts of the companies’ “long-standing synergy.”

When confronted with evidence that it had received a large payment from Low, Henley maintained it had done nothing wrong, but conceded that the real estate transaction was “an example from which Henley & Partners should and did learn.”

Maira Martini, a policy expert on corrupt money flows at Transparency International, questioned the ethics of rejecting Low as a client, then profiting from selling him real estate.

“As a PEP and high-risk client, according to H&P’s own assessment, they should have undertaken enhanced due diligence and reported any suspicious transactions to authorities,” she said.

“Instead of that, they [not only] decided to refer the client to another firm in exchange for a fat commission for the citizenship application, but seem to have continued behind the scenes to assist Low to find a real estate property in Cyprus — for an even fatter commission.”

A 1MDB Enclave in Cyprus?

Low wasn’t the only person involved in the 1MDB scandal who was seeking E.U. citizenship. OCCRP has found that around the same time he applied for Cypriot citizenship, one of his closest 1MDB associates did too. His brother, who helped him funnel millions of dollars out of Malaysia, then applied in September 2015, as did another close aide. All three listed Cyprus addresses in the same area as Low’s villa.

Low’s brother and two associates who applied for Cypriot citizenship are all accused by the U.S. Justice Department of abetting his theft of Malaysian government funds.

They are:

- Low Taek Szen — Low’s older brother and managing director of Jynwel Capital, his Hong-Kong-based financial vehicle. According to the U.S. Justice Department, he was the owner of a BSI Bank account in Singapore that was used to move millions of dollars.

- Loo Ai Swan (a.k.a. Jasmine Ai Swan) — a Malaysian national who served as 1MDB’s general counsel in 2012 and 2013. She was identified by the U.S. Justice Department as the main point of contact between 1MDB and Goldman Sachs, which helped raise billions of dollars for the Malaysian fund. (Goldman admitted last year that its Malaysian office had ignored red flags and paid bribes to officials there).

- Tan Kim Loong (aka Eric Tan) — reportedly one of Low’s closest aides. According to the U.S. Justice Department, he controlled the Singapore bank account through which part of the stolen funds was laundered.

Loo Ai Swan and Tan Kim Loong were named as key figures in the 2016 U.S. civil lawsuit seeking to reclaim assets bought with stolen 1MDB money. In December 2018, a Malaysian court reportedly issued warrants for their arrest. Their whereabouts are unknown.

Cypriot Interior Minister Nicos Nouris told OCCRP that none of the three was granted citizenship. He declined to comment on their property acquisitions, citing the ongoing investigation into Low’s citizenship.

Documents obtained by the Sarawak Report and shared with OCCRP show that Low tried to purchase the Cypriot Development Bank, a small lender that would later be fined for violating anti-money laundering regulations.

Sheikh Jaber al-Mubarak al-Sabah, a member of Kuwait’s royal family who had become one of Low’s favorite fixers, embarked on negotiations to buy the bank on his behalf in June 2016, with FidesCorp as a broker.

In a letter, Sheikh Sabah mandated FidesCorp to negotiate “the acquisition of no less than 51% and up to 100% of the share capital of Cyprus Development Bank for the maximum bid amount of 80 million euros for 100% stake.” The document went on to say that this “be done in coordination with my advisors such as Mr Bashar Kiwan, Mr Low Taek Jho or Mr Hamad Al-Wazzan.”

According to people familiar with the events who spoke to OCCRP on condition of anonymity, when FidesCorp asked Sheikh Sabah to transfer the money for the purchase, he suddenly disappeared.

The reasons for this lack of follow-through are unknown. Perhaps another solution had been found: Later that summer, Sheikh Sabah was reportedly helping Low open offshore accounts at his own small bank in the Comoro Islands. Cyprus Development Bank told OCCRP that it had never received the proposal from Low and had no relationship with him.More

By 2019, Low was one of the most famous fugitives in the world. But this didn’t prevent his Cypriot service providers from lending a helping hand yet again.

That May, his girlfriend, Jesselynn Chuan Teik Ying, applied for a Cypriot passport, with FidesCorp acting as her agent.

Ying was not as lucky as Low. By the time she applied, her boyfriend’s citizenship application had become public knowledge, sparking widespread anger and prompting the government to launch an investigation into how a man accused of stealing billions had bought his way into Cyprus.

Her application was withdrawn around the same time the scandal broke.

In October 2019, Low struck a 700-million-dollar deal with the U.S. Department of Justice. He agreed to forfeit assets including high-end real estate in the U.S. and the U.K., and return tens of millions of dollars in investments he had allegedly made with funds misappropriated from the 1MDB.

His whereabouts, as well as those of Low Taek Szen, Loo Ai Swan, Tan Kim Loong, and Jesselynn Chuan Teik Ying, remain unknown. The government of Cyprus announced in October that it would begin the process of revoking Low’s passport, but at the moment his citizenship status is unclear.