The Swiss giant Vitol holds the lion’s share of the market in Kazakhstan. The company was already marketing nearly a quarter of Kazakh crude earmarked for export in 2014; it then obtained strategic access to the biggest oil fields in the country. What’s the recipe for such success? Through access to exclusive documents, Public Eye reveals that Vitol has entered into a partnership with individuals close to the ruling powers in Kazakhstan through a discrete joint venture – Ingma Holding BV – and that the President’s son-in-law, Timur Kulibayev, has indirectly benefitted from this lucrative alliance.

Welcome to Kazakhstan

Where the story unfolds

“Dobro pojhalovat’ v Kazakhstan” — “Welcome to Kazakhstan,” a country five times the size of France whose natural resources act as a magnet for commodity firms and traders. Kazakhstan and its capital Astana, with its futuristic decor, its uranium, nickel and coal mines, its 240 oil and gas fields that contain the world’s 12th largest proven reserves of ‘black gold.’

Since 1990, Kazakhstan has been ruled by Nursultan Nazarbayev, the 78-year-old all-powerful ‘father of the nation’. Since 2015 he has proudly enjoyed the title of the elected leader with the greatest mandate having won with 97.9% of the vote. In 2014, he was also chosen as ‘best dictator’ of the year, or the man who had ‘best pillaged his country’s resources for his own benefit’ by the French organisation Geopolitical Crime Observatory. This multi-billionaire president rules with an entourage of family and oligarchs who control entire sectors of the economy.

Black gold serves the powers that be

Oil accounts for 35–50% of state revenue and 57% of export revenue in this large central Asian nation, ranked 122nd (of 180) on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. In the first half of 2017, 45% of the crude oil imported by Switzerland came from Kazakhstan; according to Swiss federal customs authorities, Kazakhstan is Switzerland’s second largest supplier behind Nigeria.

The Kazakh oil sector has been part-privatised since the mid-1990s and has been opened up to significant foreign investment. Yet the state – or specifically the ruling clan – has kept a tight grip on this strategic sector. As a shareholder in the best oil businesses, the government controls three quarters of the country’s pipelines and grants contracts for natural resource exploitation.

Natural resource revenue helps cement the far-reaching power and prosperity of Nazarbayev and his entourage. The presidential family and individuals close to him have been able to accumulate tremendous wealth.

The ruling clan has been able to accumulate tremendous wealth from natural resource rents.

The ‘ideal’ son-in-law

One man in particular has set himself up to lead this oil dynasty: Timur Kulibayev, the husband of Dinara Kulibayeva, the Kazakh President’s middle daughter. In January 2018, he was named Businessman of the Year by the Kazakh edition of Forbes Magazine. Today he is estimated to be worth US$3 billion, on equal footing with his wife who has also become hugely wealthy.

The influential son-in-law’s trademark has been constant mixing of public and private affairs. From 1997 to 2011, his main role was as a senior civil servant, notably serving as a member of the executive board of the state oil and gas company KazMunayGas (KMG) and subsequently at the sovereign wealth fund Samruk Kazyna (SK), whose portfolio is 62% comprised of stakes in state oil and gas companies. In parallel, the President’s son-in-law held private interests in the oil sector, administered by third parties, as permitted by Kazakh law.

Today, he no longer plays an official role within government and dedicates his time to making his business empire a success, yet Kulibayev remains head of an important energy lobby group, Kazenergy, and continues to call the shots in the oil sector.

In this environment – in which the line between the public and private sectors is extremely blurred – a Swiss trading company has managed to work its way to the top.

Vitol goes after Kazakh black gold

The name Vitol may be a familiar one. The biggest private oil trader in the world is also Switzerland’s second largest company; in 2017 its revenue was US$181 billion. Comfortably housed at 28 Boulevard du Pont‑d’Arve in Geneva, this business giant has never shied away from going after markets where corruption is endemic – be it in Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, Serbia or Venezuela. As Russell Hardy, one of its directors, put it modestly in 2016, the company grew through acquisitions using the motto “opportunity is defined externally”.

This motto also applies to Kazakhstan, which gained independence when the USSR collapsed in 1991. Since then, Vitol has been quick off the blocks to seize a large share of the market. Nearly three decades later, it has risen impressively in the country:

“Nowadays, Vitol practically shares the Kazakh market with Chinese companies and leaves mere crumbs for others”,

Blessings from above

From 2015 to 2018, Vitol achieved a masterstroke by winning two tender processes to provide a total of US$5.2 billion of pre-financing (loans) to KazMunayGas, the national oil company. Vitol will be refunded over a five-year period through shipments of oil from the country’s two giant fields, Tengiz and Kashagan, in which KazMunayGas is a shareholder. This contract, known in industry jargon as a ‘cash for crude deal’ guarantees privileged access to Kazakh crude and excellent long-term relations with the state.

Our investigation tells the story of Vitol in Kazakhstan – based on exclusive access to documents.

What the ‘KazakhLeaks’ reveal

Leaked documents reveal the friendly conversations between two Vitol executives and individuals close to the President.

When you discuss transparency in the resource sector with Vitol managers, they recoil. In March 2018, David Fransen, the company’s chairman in Geneva, stated:

“What is important in our eyes is that the primary motivation (…) is combatting corruption rather than systematically and publicly ripping apart every deal we make.”

Public Eye undertook its investigation with precisely this motivation.

Living up to its reputation of being a ‘black box’, Vitol has always drip-fed information about its business in Kazakhstan. In 2013, the British news agency Reuters attempted to analyse its dominant position, reporting that Vitol had found a niche in which it “aggregate[s] small parcels from all Kazakh producers into full tanker-size portions.” In one month, Vitol filled 9 tankers worth approximately US$700 million, which would mean the annual turnover of the company could have reached about US$8 billion. Eight other tankers followed swiftly. Responding to these figures, Vitol highlighted its exemplary business practices, voicing its “pride in its long-standing partnership with the Kazakh oil industry”.

Yet what is the basis of this “long-standing partnership with the Kazakh oil industry”? Providing an answer to this question would not have been possible were it not for an extraordinary data leak, which gave us a glimpse behind the scenes.

Living up to its reputation as a ‘black box’, Vitol has always drip-fed information about its business in Kazakhstan.

Kazaword reveals its secrets

From the summer of 2014 to the end of 2016, an anonymous platform called Kazaword appeared online, divulging emails and documents hacked from the inboxes of top-level Kazakh managers.

Likely initiated by the banker Mukhtar Abliazov, archenemy of President Nazarbayev who the Kazakh courts accuse of having embezzled billions of dollars, the ‘KazakhLeaks’ shone the harsh light of day on the practices of the ruling clan. Several media outlets covered the story, in particular revealing that the government in Astana had engaged a host of lobby groups to burnish its image, including the former Swiss ambassador Thomas Borer. In 2015 the Kazakh authorities filed a complaint against what they claimed was widespread hacking, thereby confirming the authenticity of the documents.

Vitol’s privileged relations

Thanks to Kazaword, Public Eye gained access to correspondence between Vitol executives and two Kazakh multimillionaires, Dias Suleimenov and Daniyar Abulgazin. Their correspondence dates from 2009 to 2015. The first question is: who are these two men?

Brothers-in-law Suleimenov and Abulgazin worked their way up to the highest levels of power and business in Kazakhstan. They are close to the President’s son-in-law Timur Kulibayev, like the latter, they held top-level positions in the big state oil and gas companies while at the same time ensuring the success of their private businesses. After quitting government service, the trio continued to work in private oil companies and energy lobby groups. They are ‘politically exposed persons’ (PEPs) under the definition established in Swiss money laundering legislation.

Business relationships with PEPs requires Swiss bankers – subject to Swiss money laundering legislation – to conduct in-depth due diligence. In contrast, commodities traders are not subject to any legislation or due diligence requirements in this regard. Rather than a risk, PEPs are seen as a sign of business opportunities. This is evident from the emails discovered on Kazaword, which reveal Vitol’s astonishing proximity to the individuals close to the ruling powers.

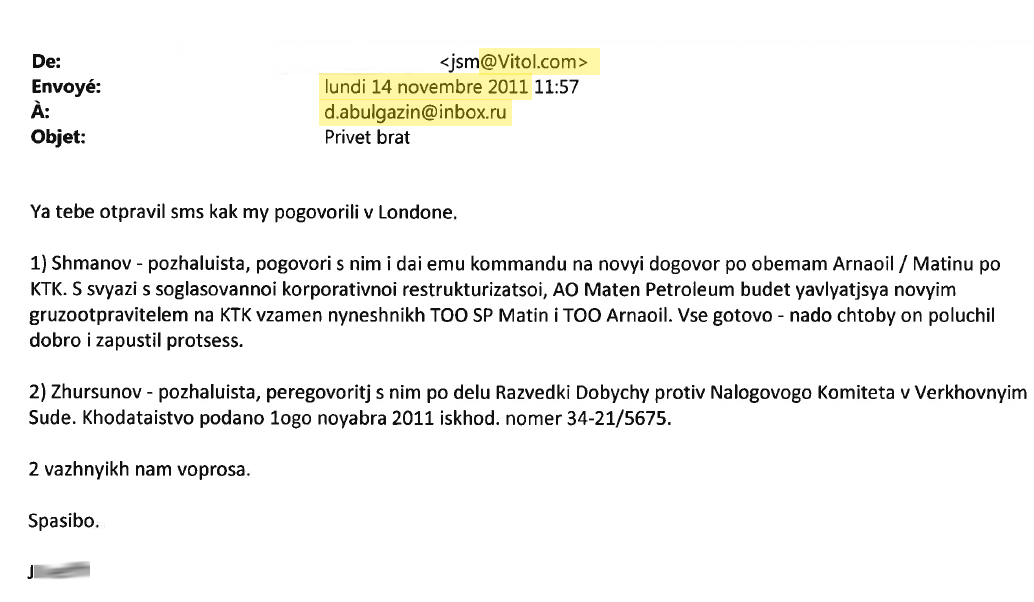

« Privet Brat ! »

«Hey bro!» wrote Vitol’s Head of Central Asia and Russia in a message sent to Daniyar Abulgazin on 14 November 2011. At the time, he held a strategic post in the Samrouk-Kazyna, Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth fund, then overseen by Timur Kulibayev. Abulgazin was tasked with managing its shares in oil and gas, including those in KazMunayGas.

In the email, Vitol’s executive asked his ‘bro’ to deal with an oil and tax matter – even giving him instructions regarding the “two issues that are important to us”, without needing to give any indication of what he was referring to.

The tone between Vitol and the top dogs of the Kazakh ruling elite had been set.

The mysterious Ingma

An intriguing joint venture between Vitol and a small offshore company yields incredible returns

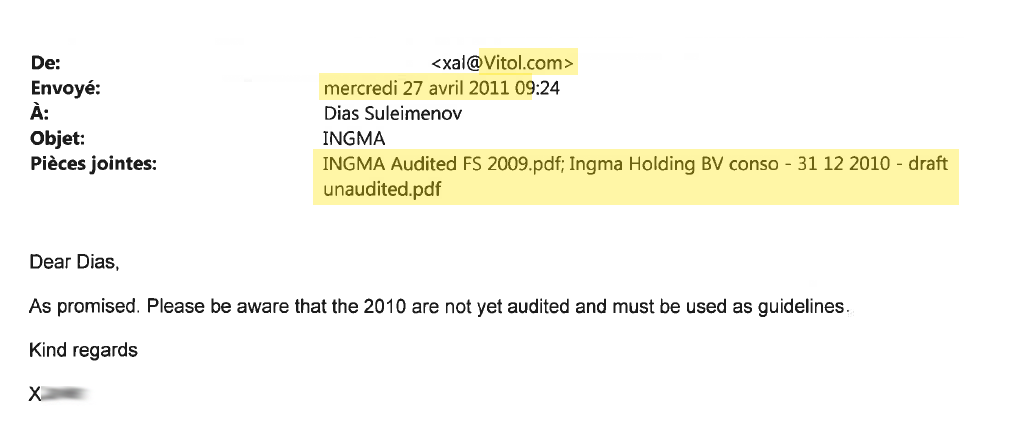

In Dias Suleimenov’s hacked inbox an absolute gem was discovered. In a short message from a Vitol trader based in London, received on 27 April 2011, the 2009 and 2010 financial reports of Ingma Holding BV were attached.

There is no trace of Ingma Holding BV, a joint venture that specialises in the oil business, in Vitol’s company brochures or on its website. And yet this company, registered by Vitol in Rotterdam in 2003, is the key to Vitol’s success in Kazakhstan but had always flown under the radar – or nearly.

Two years ago, the British daily The Independent briefly referred to it simply as Ingma. The newspaper questioned the opacity of the entity, set up by Vitol in order to “invest in Kazakhstan”. Asked who stood behind Ingma, according The Independent, “Vitol strenuously denies claims that Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev, his son-in-law Timur Kulibayev or others owing their positions to them are beneficiaries.” Nevertheless, the company refused to identify who the beneficiaries actually are. Public Eye’s subsequent queries received the same response.

The cash machine Ingma Holding BV

The documents found on Kazaword as well as others that Public Eye gained access to shone light onto the mysterious Ingma. The results were astonishing: in 2009, inconspicuous Ingma was a company with shares worth over a billion dollars, made up of 10 subsidiaries, four of which are registered in Switzerland – in Geneva, Baar and Lausanne.

Mainly active in “trading crude oil and petroleum products”, in 2009 Ingma enjoyed nearly US$8 billion in revenue and US$124 million in net profit. In 2010, its revenue reached US$20 billion according to the unaudited report sent by Vitol to Dias Suleimenov, which equates to 10% of the total revenue generated that year by the Vitol through all of its activities in the world.

Using the Dutch company register Public Eye was able to complete the picture for the years 2011 – 2016 (financial reports for years prior to 2009 are no longer available). From 2009 to 2016, Ingma’s revenue reached US$93.9 billion, with net profits of US$1.1 billion. This is an impressive figure for a company that never had more than 11 employees. Commenting on these financial results, a former trade finance banker in Geneva commented:

« Such volumes are enormous for a private company. I thought you were talking about a subsidiary of the state oil company KazMunayGas. »

A major actor

Using the revenue figures disclosed by the Kazakh state to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2015 and 2016, Public Eye was able to estimate that Ingma’s sales accounted for 18–20% of all the Astana government’s export revenues generated by crude oil in these two years.

In a promotional brochure discovered on Kazaword, which has never been published, Vitol congratulates itself on “20 years of experience in Kazakhstan”. Once again the statistics tell the story –, the Geneva-based trader Vitol claims that in 2014 it traded 21% of the 62.45 million tonnes of oil sold by Kazakhstan, which equates to an average of seven tanker deliveries a month. Although never mentioned by name, Ingma clearly plays an instrumental role in this trade.

Copious dividends

The last but by no means least piece of information revealed by Ingma’s financial reports is that the joint venture paid out nearly all of its profits in the form of dividends. Over a billion dollars effectively landed in its shareholder’s pockets from 2009 to 2016 – and that is an incomplete figure because the figures for 2010 and 2012 are lacking.

But who are Ingma’s mysterious shareholders?

The right-hand man

Introducing Arvind Tiku. Simultaneously Vitol’s partner in Ingma and proprietor of companies from which Timur Kulibayev indirectly profits

It’s easy to get lost in the maze that is Ingma Holding BV and its numerous subsidiaries, which are registered in Switzerland as well as the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria. While the number of subsidiaries and shares has fluctuated at a startling pace over the years, the structure of their capital is always the same.

The majority shareholder in Ingma is then Oilex NV, a small company set up in 2002 in Curaçao, the tax haven of the Dutch Antilles. During these years, Oilex NV held 51% of Ingma’s shares while Vitol FSU BV, Vitol’s Dutch subsidiary, owned the remaining 49%; a strange alliance between a world-renowned trading company and an obscure offshore company.

Who owns Oilex? At the end of 2009, its headquarters were transferred to Luxembourg, making it possible to discover the name of the sole shareholder named in the company register – Arvind Tiku a bussinessmn of Indian origins. His company Nelson Resources Limited quietly acquired stakes in numerous oil fields and Tiku was also head of a host of other offshore companies active in oil trading. He is also Timur Kulibayev’s right-hand man and business partner.

Ingma Holding BV? A strange alliance between a trading company known around the world and an obscure offshore company

A duo under investigation

From September 2010, Timur Kulibayev and Arvind Tiku were also connected in the face of adversity. Just as Ingma Holding BV was earning billions of dollars, the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland (OAG) opened an investigation into money laundering, directly targeting President Nazarbayev’s son-in-law and his partner, who were suspected of having organised the sale of under-priced oil assets in Kazakhstan. The two men had allegedly received bribes that had ended up in numerous Swiss banks. The affair was not linked to Vitol.

The case caused quite a stir and yet was closed after three years of investigations had failed to prove that the funds had been acquired unlawfully. The Swiss prosecutors requested help from their Kazakh counterparts, who concluded that no crime had been committed. Such an outcome is hardly surprising in a country where according to an OECD report “courts are controlled by the ruling elite” and “corruption is said to be present at all stages of the judicial process”.

Nevertheless, Public Eye gained access to legal documents in which several sections detail how Arvind Tiku and Timur Kulibayev were happily mixing their revenues and investments. This raises questions as to the role of the President’s son-in-law in Vitol’s partnership with Arvind Tiku.

An explosive document

The letter is dated 23 October 2008, addressed to a Credit Suisse banker by one ‘JN Gupta’, Arvind Tiku’s financial advisor. He is writing on behalf of the President’s son-in-law, freshly appointed as the head of Samrouk-Kazyna, Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth fund. Mr Gupta wants to push back the deadline for repaying a loan granted to Merix International Venture Limited, an offshore company belonging to Timur Kulibayev. In doing so, he makes assurances that the remainder of the loan will be paid off “through dividends or loans from our operating companies”.

Surprise – one of the six operating companies presented as belonging to Kulibayev is Vitol Central Asia, registered in Geneva in 2003. According to the letter, the company is a joint venture in which Vitol has a 51% stake. The letter states:

« This joint venture has been transporting Kazakh crude oil via a pipeline to the port on the Black Sea. The volume of sales is 6 million tonnes [per year] »

It is important to note that Vitol Central Asia is a subsidiary of Ingma, therefore the above-mentioned « joint venture » refers to Ingma (the partnership between Oilex and Vitol). Vitol Central Asia currently exports all of the oil from the Ayrankol Field exploited by the company Kaspyi Oil – which in turn is 100% owned by Timur Kulibayev.

According to this letter, the President’s son-in-law does indeed indirectly benefit from Vitol Central Asia, that is, from Ingma. The billionaire may not be a Vitol Central Asia shareholder on paper, but he is willing to dip into the dividends of this subsidiary to repay his bank loans. Is Gupta simply misleading Credit Suisse? Or is Arvind Tiku in fact one of Timur Kulibayev’s frontmen?

When contacted by Public Eye, Arvind Tiku declined to comment while Timur Kulibayev responded through the lobby group Kazenergy, claiming to have always acted in conformity with the applicable regulations regarding private and state activities. According to Kazenergy, Mr Kulibayev has “always followed all such rules and regulations in full accordance with the requirements”, adding that he “does not exercise management control over any company in which he holds an interest.”Kazenergy confirmed Kulibayev indirectly owns Merix. According to them, the letter addressed to Credit Suisse contains incorrect information: “It is not correct that these companies (ie Vitol Central Asia SA, Ingma Holding BV or Euro Asian Oil AG), were ever ‘part of Mr Kulibayev’s operating companies’.”

According to Vitol, “Merix Ventures International has never been a shareholder of Vitol Central Asia SA” and “Mr Kulibayev is not a direct or indirect beneficiary of Ingma. It is incorrect to state or suggest otherwise”. Vitol vehemently denies that the President’s son-in-law directly or indirectly benefits from profits generated by the joint venture. This “has been confirmed by the due diligence of all the major international banks which have a commercial relationship with Ingma.”

Public Eye’s investigation shows that the situation is not quite so cut and dry.

« Follow the money »

Public Eye’s research shows that Arvind Tiku shares his money with the Kazakh President’s son-in-law in a trust held at Credit Suisse, which has had nearly US$600 million paid into it – US$100 million of which came from Oilex.

The Swiss judicial investigation also uncovered a trust set up in 2006 and administered by Credit Suisse, in which the ‘Tiku-Kulibayev’ duo pool their funds. From May to August 2006 the trust, which contains an investment fund known as Handoxx, took in nearly US$600 million from three companies, none of which officially belongs to Timur Kulibayev. One of the companies is Oilex NV, the company that jointly owns Ingma with Vitol. Oilex paid over US$100 million into the trust in two tranches. The money came from the Geneva branch of BNP Paribas where Oilex has its bank accounts – as can be seen in a document from the bank included in the court files.

Generous transfers

What happened to these funds? In 2007, the investment fund Handoxx paid out US$283 million from the trust in the form of zero-interest loans granted to Merix International Ventures (the company belonging to Timur Kulibayev). Notably, these funds enabled the Kazakh billionaire to purchase luxury properties in the United Kingdom, including that of Prince Andrew. Clearly extremely generous, Arvind Tiku also awarded Merix a loan of US$101 dollars via Oilex.

Confronted with the fact that its partner Arvind Tiku was pooling his funds in a trust shared by the Kazakh President’s son-in-law and directly fed by Oilex, and the fact that the latter was loaning it nine-figure sums, Vitol stated it “is neither a shareholder in Handoxx nor Oilex and is therefore unable to comment on purported payments made between the two companies.” Neither Arvind Tiku nor Timur Kulibayev have responded to clarify this point.

Business as usual?

For the purposes of the investigation, the Swiss Office of the Attorney General had ordered the Tiku-Kulibayev accounts to be blocked, including two belonging to the company Oilex; they were frozen until November 2011. It was an embarrassing situation for Vitol, whose code of conduct claims to “not tolerate bribery or corruption”. Regardless, the company continued its lucrative business dealings with Arvind Tiku.

The ‘comrades’

We learn that the new arrival within Ingma, Dias Suleimenov, is another of Timur Kulibayev’s loyal followers. In 2011, he received US$11.8 million in dividends at HSBC Geneva.

In 2010, while the prosecutors were working in Berne, Ingma Holding BV continued to run its oil business. As the judicial storm clouds were building, Ingma Holding BV restructured its capital. A new entity, Omega Coöperatief UA, took a 10% stake in the joint venture, leaving Oilex Sàrl (Arvind Tiku), now renamed Xena Investments Sàrl, with 47.5% and Vitol FSU BV with 42.5%.

Who does Omega Coöperatief UA belong to? In Kazaword, we discover that Dias Suleimenov – whose inbox was hacked – is one of the beneficial owners of the Dutch company owned by several offshore companies. According to its 2009 financial report, at the end of that year Ingma acquired the oil trading company Euro Asian Oil AG belonging to Dias Suleimenov and probably to Daniyar Abulgazin for US$45 million. This transaction enabled Omega Coöperatief UA to acquire the 10% stake in Ingma. According to a source familiar with the matter, Daniyar Abulgazin also has interests in Omega, probably on an equal footing with Dias Suleimenov. Abulgazin held high-level state positions within Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth fund, Samrouk-Kazyna, until 2012.

In the shadow of the mentor

Of all Timur Kulibayev’s partners, Suleimenov is undoubtedly the most loyal. The two men share the same love of the chic suburbs of Geneva, where their spouses have settled just a few kilometres apart. At the end of 2009, Dinara, Timur’s wife and the Kazakh President’s daughter, bought a palace in Anières for CHF 74.7 million. According to a June 2018 report released by the Swiss investigative TV programme Temps présent, in 2010 Dias’s wife Alina bought a plot of land in Cologny where she had a luxury property built, estimated to be worth CHF 40 million. Kazaword revealed that Suleimenov even manages some of Dinara’s living expenses in Switzerland, dealing with bills and complaints.

Dias Suleimenov grew up in the shadow of Timur Kulibayev, from 2003 working in the logistics department of the giant KazMunayGas (KMG), where his protector was number two. From 2004 to 2006, he headed the Trading House JSC KazMunayGas(THKMG), a branch of KMG that controls a share of Kazakhstan’s crude exports with offices in London, Lugano, Dubai, Singapore and Astana. Even after this date – again revealed by Kazaword – he remained in contact with employees of the THKMG branch in Lugano as if he were still the boss.

Vitol’s complaints

On 7 December 2009, Vitol’s Head of Central Asia and Russia wrote an email to Suleimenov – with Arvind Tiku in CC – complaining about the competition. Gunvor had bought “10,000 tonnes of Russian crude oil” and shipped the cargo to Socar Trading (Azerbaijan’s state company) using two tankers based in Aktau, the biggest port in western Kazakhstan, located on the Caspian Sea where Vitol had invested. The email implores

« We must get this stopped. Just crazy. Sorry but this is a big problem and totally emblematic of the bordak [mess] at Aktau which is also now endangering our business and margins. »

We do not know whether Suleimenov was able to ‘deal with the issue’ or what means he could have used to do so. At the time, Suleimenov was managing Petroleum Operating LLP, a private petroleum logistics company in which his inseparable brother-in-law Daniyar Abulgazin, and also Timur Kulibayev, are shareholders. According to our information, Suleimenov already had a foot in Ingma.

When it responded to Public Eye’s enquiry, Vitol confirmed that Xena Investment Sàrl (ex-Oilex), Vitol FSU BV and Omega Coöperatief UA are the shareholders of Ingma Holding BV’s, stating that

« due to Swiss privacy and data protection laws, we are unable to provide any information to third parties regarding the persons associated with Omega. »

Through his lawyer, Dias Suleimenov informed Public Eye that he does

« not comment on private business matters and that he did not wish the information to be published because it is not in the public domain and therefore must have been obtained through unlawful means. »

Daniyar Abulgazin did not respond to Public Eye’s questions.

Our conclusions

Here we share our demands in the form of an epilogue

There are two ways for commodities traders operating in jurisdictions where the rule of law is weak to gain market share. Both are risky and rely on the fact that commodity trading is not regulated in Switzerland.

Strategy n°1

The traditional strategy involves outsourcing the risk by paying intermediaries. As soon as anti-corruption agreements have been signed, the intermediary is free to pay all or part of their commission to public officials tasked with awarding the desired contract. As Public Eye painstakingly exposed, this is the option chosen by Gunvor in Congo-Brazzaville – and that caused the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland to initiate proceedings against the company for possible organisational shortcomings.

Strategy n°2

Just as adventurous, the second strategy involves association with politically exposed persons (PEPs) in a joint venture which can then enter into contracts. From 2003 onwards, Vitol opted for one such alliance in Kazakhstan, enabling the world’s biggest private oil trader to market huge volumes of Kazakh crude through Ingma Holding BV. From 2009 to 2016, this unknown company paid out at least US$1 billion in dividends to its shareholders, distributed between Vitol and its partners: firstly, to Arvind Tiku alone through Oilex, then as from 2010 onwards to Dias Suleimenov and probably Daniyar Abulgazin, through Omega. Our investigation also shows that even though his name does not appear on paper, the President’s son-in-law Timur Kulibayev indirectly benefitted from this partnership.

Has the risk really been covered?

Vitol recognises that it had a direct or indirect business relationship with the PEPs Arvind Tiku, Dias Suleimenov, Timur Kulibayev and Daniyar Abulgazin. The company does not believe that this breaches its code of conduct:

« It is appropriate and often necessary for companies to enter into business activities with PEPs. Enhanced due diligence checks are performed on any transaction involving a PEP. »

Vitol vehemently denies that Timur Kulibayev is or ever has been the direct or indirect beneficiary of Ingma. The company claims that it cannot comment on the financial links between Arvind Tiku and the President’s son-in-law because it does not hold shares in either Oilex or the trust. Is this response satisfactory? In light of the context in Kazakhstan, where the ruling clan amasses huge wealth off the back of the oil industry, our answer is no. Careful due diligence would have uncovered the close relationship between Tiku and Kulibajew, in 2010 at the latest when the press began to report on the Swiss investigation into the two.

A misleading argument

According to Vitol, the banks involved in Ingma’s commercial activities did not detect the presence of Kulibayev in the shadows of Arvind Tiku. Precisely this situation reveals the weakness of one of the main arguments put forward by the industry’s lobby and the Swiss federal authorities in opposition to any semblance of regulation; namely, that commodity trading is indirectly regulated by the banks that fund their activities.

In 2011 the Wolfsberg Group, which brings together 13 of the biggest international banks in an effort to prevent money laundering, stressed the limits of their supervisory powers, stating

« it is extremely rare for any one Bank to have the opportunity to review an overall trade financing process in complete detail given the premise of the trade business that banks deal only in documents »

Moreover, the traders themselves provide these documents.

Essential measures

The case of Vitol in Kazakhstan shows the need to apply binding provisions to the commodities trading sector at three levels:

- Transparency of payments to governments

- Transparency of beneficial ownership

- A duty of due diligence regarding business partners

In light of the risky business model of companies like Vitol, the latter point is crucial. Traders must be obligated by law to apply heightened due diligence checks to reduce corruption risk when they enter into business relationships with PEPs. Introducing such a requirement would serve a dual purpose. Firstly, it would be preventive by obliging traders to ask themselves the right questions and to document their practices. Secondly, it would be repressive because it would provide the basis for sanctions in the event of non-compliance.

Although the Federal Council has recognised that Switzerland has a particular responsibility as the world’s biggest commodities trading hub, it still refuses to act to mitigate the risks. Instead of welcoming Kazakh oligarchs and their fortunes with open arms, Switzerland should finally establish a Commodity Market Supervisory Authority to regulate the sector in order to minimise Switzerland’s contribution to the ‘resource curse.’

Shining a light where nefarious people prefer their activities to remain hidden in the shadows, denouncing harmful actions and proposing specific solutions: these are Public Eye’s aims.

We fight against injustice that has a significant link to Switzerland and demand the respect of human rights around the world. Through our research, advocacy and campaigning, we express the voice of close to 25,000 members in calling for a responsible Switzerland. Public Eye: focusing on global justice.

Investigation : Agathe Duparc, with Camille Chappuis, Marc Guéniat and Andreas Missbach

Editing : Géraldine Viret

Online: Floriane Fischer & Raphaël de Riedmatten, in collaboration with Opak