From faraway Kazakhstan, an obscure brokerage says it scores hot U.S. IPOs.

Six thousand miles from Wall Street, in the ancient Silk Road city of Almaty, lies the private redoubt of a little-known financial empire.

Inside the members-only T-Club, two cockatoos, Grisha and Silvia, keep watch. Above a bronze samovar, a flat screen television shows the proprietor’s corporate crest: a green “F” on a green shield.

Few can explain exactly what’s going on here — how an obscure brokerage in Kazakhstan, of all places, has outrun Wall Street firms.

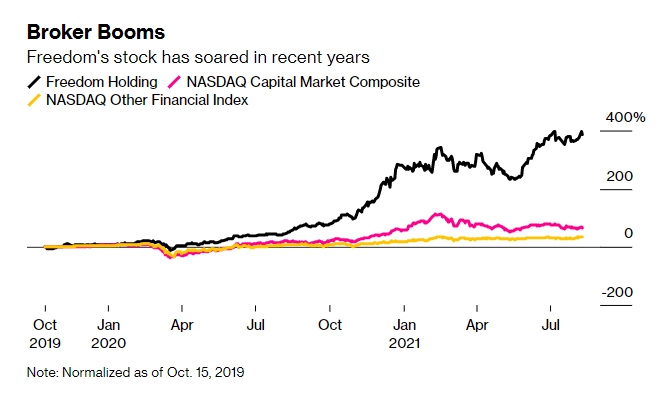

But outrun them it has, and then some, at least in the stock market. Over the past couple of years, the share price of Freedom Holding Corp. – the company whose “F” logo is on that green crest — has soared about 500%.

How? The young billionaire with the answers, Timur Turlov, is sitting at the table over there. Wearing a tailored blue suit and sipping a Red Bull, Turlov, 33, sketches out a grand vision for the broker.

“We remain one of the few floodgates to the Western market for customers from our region,” Turlov says in his native Russian, while detailing the unique arrangement he says has helped secure Freedom access to newly listed U.S. stocks.

There’s a mysterious hedge fund with deep connections across Wall Street; a trading conduit through Belize that Turlov personally controls; an obscure New York brokerage with a troubled past.

According to Turlov, founder of Freedom, this setup has secured access to hot new stocks in America, a pitch that helped make his company’s name. Freedom, he says, is giving Russians, Kazakhs, Uzbeks and Ukrainians a piece of the Wall Street action.

One more twist: the more shares in Freedom his clients buy, the more of those hot U.S. stocks they will get, Bloomberg has previously reported.

According to Freedom marketing materials, clients have gotten in on more than 100 U.S. IPOs since 2020, including Airbnb Inc., Bumble Inc. and South Korean e-commerce giant Coupang Inc. Such access is virtually impossible for small brokers and wealth managers who are actually based in the U.S. to secure.

Turlov says his firm’s way in is an affiliate of a hedge fund that buys the shares from underwriters and passes them along. Its identity is confidential, he says, and no mention of it appears in U.S. filings. Even inside Freedom, the name is closely guarded, according to current and former employees.

The arrangement is unusual, to say the least. Reena Aggarwal, director of Georgetown University’s Center for Financial Markets & Policy, says she’s never seen anything like it.

Freedom is doing it all under the gaze of U.S. authorities. The group is based in Almaty but its listed entity is registered in Las Vegas. Its stock is traded on the Nasdaq, where the company is currently worth about $4 billion.

Inside the T-Club, Turlov’s smartphone keeps buzzing. Tall and boyish-looking, in a purple tie, Turlov turns serious as he outlines Freedom’s ambitions. In January, it acquired New York-based broker Prime Executions Inc., and Turlov says he’s looking to expand further. In June, Standard & Poor’s said it expected Freedom’s “robust earnings” to continue at least into 2022.

Kazakhstan Economy

To the uninitiated, Kazakhstan may be best known for “Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan,” the 2006 Sacha Baron Cohen comedy that so infuriated the Kazakh government.

But this Central Asian nation of 19 million is one of the most prosperous former Soviet republics. Its mineral and oil wealth has added to the region’s affluent elite, many of whom are eager to play the markets. Sensing opportunity, Turlov founded Freedom in 2008.

Today his firm has around 100 branches and offices, from the Kazakh capital Nur-Sultan, to the Russian resort city of Sochi, to Kyiv in Ukraine. Freedom is headquartered in the tallest building in Almaty, a glass-and-steel skyscraper next to a shopping mall with luxury boutiques like Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada.

A Moscow native and citizen of Russia — and also St. Kitts and Nevis in the Caribbean — Turlov controls almost three quarters of Freedom. As the company’s stock price has soared, he’s become a billionaire several times over.

Minting Money

The IPO business may attract the most attention, but Turlov says it is an increasingly marginal part of the business. He says Freedom doesn’t receive significant allocations and today the business makes up only about 10% of Freedom’s revenue.

Freedom Holding has been minting money nonetheless, with customers gravitating to trading stocks and fixed income investments. Its pre-tax profit jumped more than six-fold to $173 million in the fiscal year ended March 31. During the same period, the number of its customer accounts doubled, to 290,000 — a huge figure for the region, albeit a pittance next to the 22.5 million at newly public Robinhood Markets Inc.

Turlov’s own profile has also soared. In 2018, he backed “Financier,” a glossy financial drama (think an Almaty-based “Margin Call”). One of the brokerages in the film, Partner Finance, sports a logo similar to Freedom’s.

His larger-than-life image continues to draw clients — as does hoped-for access to myriad U.S. listings. A section of Freedom’s website lays out the pitch. “Buy stocks at their initial price before trading begins,” it runs. “Prices can grow by tens or even hundreds of percent!”

This ability to access IPOs “is Freedom’s specialty, their absolute advantage,” said Daniyar Temirbayev, who heads the Qazaq Association of Minority Shareholders, a lobbying group for investors in the country’s burgeoning stock market.

Four Freedom customers interviewed by Bloomberg, who all asked not to be identified, confirmed they received allocations to U.S. IPOs — and that they bought Freedom shares to increase their allocations.

Oversubscribed IPOs

Exactly how Turlov does all of this remains a puzzle to outsiders. Most U.S. IPOs are oversubscribed. Everyone wants to get in early in case a stock pops on the first trading day, and Wall Street banks typically dole out stocks to favored clients first. Hedge funds and big mutual funds typically take 90%, according to Jay Ritter, a finance professor at University of Florida in Gainsville.

What are the odds an obscure player like Freedom could get in early?

“Zero,” Ritter says.

But Turlov says this is where his workaround comes in. In the T-Club, where entry is restricted to Freedom’s employees and high-rolling clients, he reveals key parts of the Freedom system.

Belize Affiliates

One is a Belize-based affiliate of the aforementioned hedge fund, which Turlov says buys the stocks from major underwriters. Another is a Belize-based affiliate of Freedom that Turlov personally owns. Once the hedge fund affiliate gets its hands on a stock, Turlov has that Belize-registered entity, FFIN Brokerage Services Inc., buy it and eventually pass it to Freedom for a fee.

Freedom customers don’t actually get their hands on the stocks for three months, an eternity in the world of IPOs. During the lock-up period, they can buy a derivative from Freedom to fix the share price where they want.

The hedge fund’s affiliate collects a commission, safe in the knowledge that Freedom clients won’t be able to flip the stock quickly, Turlov says.

According to Scott Moss, a partner at law firm Lowenstein Sandler LLP in New York, hedge funds rarely if ever act as someone else’s broker because of potential regulatory hassles.

“As a hedge fund manager, I would have huge reputational risk,” said Carsten Kotas, professor of business administration at FOM University in Frankfurt and a former trader who previously oversaw hedge funds at HSBC Holdings Plc.

The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority declined to comment on Freedom’s business practices.

Most of the IPOs that Freedom has accessed so far this year have been overseen by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Morgan Stanley. Spokespeople for the firms declined to comment on whether they were aware of any relationship between their clients and Freedom.

Demand from customers far outstrips supply, so Freedom has started a $625 million fund traded in Russia and Kazakhstan, whose holdings include some of the IPO securities — and also holds Russian sovereign debt. It was created to enable more clients to get exposure to recently listed companies, according to Turlov.

Lek Securities

Turlov names another cog in his operation: Lek Securities UK Limited, the U.K. entity of Lek Securities Corp., a New York-based brokerage. The unit temporarily holds the IPO shares purchased by the hedge fund, he says. Freedom’s European subsidiary routes the vast majority of its trades to Lek, regulatory filings show. The New York broker, small by comparison with Wall Street banks, is also one of the most active traders of many of the IPO stocks that Freedom says it has accessed, Bloomberg data show.

Lek has had run ins with U.S. regulators, including 2017 allegations that the brokerage had enabled manipulative trading by a client in Ukraine that resulted in almost $30 million of illicit profits. Lek was fined about $3 million in 2019 and founder Sam Lek was permanently banned from the securities industry.

More trouble emerged in 2018 when FINRA alleged that Lek Securities had allowed customers with dicey backgrounds to engage in some $100 million of penny-stock trades despite “numerous red flags” of potential fraud. Calling the firm a “recidivist violator” of rules, Finra fined it $200,000 in 2019.

Samuel Lek’s son Charles, who now runs the business, declined to comment.

Freedom isn’t linked to the above allegations but its own operations have drawn questions. The Foundation for Financial Journalism, a non-profit supporting investigative journalism, published a report last week examining Freedom’s corporate arrangements including Lek, various related party transactions and the execution process for the trades of its customers.

Turlov says skepticism about Freedom is inevitable. People envy his success.

“Almost any situation can become the basis for criticism,” he says.

— With assistance by Marion Dakers

Original source of article: www.bloomberg.com