The saga of Gulnara Karimova’s ill-gotten and ill-fated assets – frozen in a number of mostly European jurisdictions – may soon come to an end.

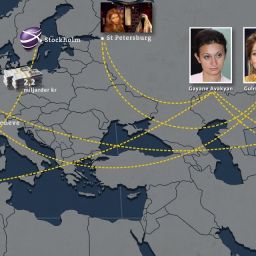

This story began in 2012, when two associates of Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of Uzbek president Islam Karimov, tried, apparently on her order, to conduct a transaction involving an account at Lombard Odier bank in Geneva, Switzerland. Shokhrukh Sabirov and Alisher Ergashev were later arrested by the Swiss police on suspicion of money laundering.

This prompted criminal investigations and forfeiture cases targeting assets belonging to Karimova, who ended her extraordinary career as a powerful oligarch and socialite with house arrest in February 2014. She later found herself in prison after being convicted for extortion and embezzlement in 2015. The assets in question are being pursued by a number of jurisdictions, including, apart from Switzerland, Sweden, the United States and The Netherlands. In 2015, the US Department of Justice filed a civil case to forfeit $850 million of cash deposited in Swiss, Irish, Belgian and Luxembourg bank accounts registered in the name of Gulnara’s associates, alongside charging telecoms international Vimpelcom $795 million as a penalty for alleged bribery in Gulnara Karimova-related case. The total amount of Karimova’s assets seems to be even larger. In Switzerland alone, $700 million has been frozen and is being targeted by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (BA) of Switzerland.

Indeed, the Swiss authorities are about to confiscate these assets. On 22 May, the BA issued two penal orders leading to the confiscation of Karimova’s assets. Karimova’s lawyers have appealed the decision. If this confiscation process is completed, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs will start negotiations with the Uzbek government over the repatriation of these assets. In principle, the decision to return them has already been made by the Swiss government.

On the one hand, this looks like the correct decision. A number of other parties are also after this money, such as some creditors of Zeromax GmbH, a company registered in the Swiss offshore zone Zug and whose beneficial owner is believed to have been Gulnara Karimova. Before going bankrupt in October 2010, Zeromax GmbH had aggressively invested in one sector of Uzbekistan’s economy after another – apparently with the support from the country’s top leadership, but to the discontent of other big players among Uzbekistan’s political and business elite. The sudden and mysterious bankruptcy of this company left creditors without compensation for their investments.

“Responsible” repatriation here means that asset return should provide a remedy to the victims of corruption, i.e. the whole population of Uzbekistan

On the other hand, a number of Uzbek civil society activists are concerned that the Swiss may return the assets without sound preconditions and, in the past few years, have advocated for responsible repatriation. “Responsible” repatriation here means that asset return should provide a remedy to the victims of corruption, i.e. the whole population of Uzbekistan. They argued that the assets should not be handed over to the government of Uzbekistan, as some top officials have avoided accountability for complicity in the Gulnara Karimova-driven corruption case.

Gulnara Karimova. Photo CC BY-SA 3.0: Timir01 / Wikipedia. Some rights reserved.

In light of the pending confiscation of Gulnara Karimova’s assets by the Swiss authorities, the same group of Uzbek activists has put forward a set of principles that should guide the repatriation of assets to Uzbekistan.

The main principle should be to consider repatriation in the context of the fight against corruption at the national and global levels. If the asset return does not contribute to this fight, then the asset-returning state (in this case, Switzerland) should be held responsible for perpetuating corruption in the asset-receiving state (Uzbekistan).

A notorious example of irresponsible asset return has been Switzerland’s 2012 transfer of $48 million to Kazakhstan – a move that has been criticised for supporting that country’s repressive and kleptocratic regime. This is not the kind of deal Uzbek activists want to see in the case of their country’s stolen assets.

Compared to previous stages of their campaign, there is some novelty in the Uzbek activists’ proposed principles, which reflect the new realities in Uzbekistan, especially President Shavkat Mirziyoev’s commitment to reform the government and its policies.

Thus, the activists call for the assets to be used as an incentive for core anti-corruption reforms, the progress of which is still very weak to date. The activists believe that such use of returned assets would act as a genuine remedy for victims of corruption and serve their best interest in the long run. If implemented consistently, the reforms would guarantee that the rights and welfare of the general population would be less negatively affected by government corruption.

The activists argue that before the assets are returned, the Government of Uzbekistan should provide concrete proofs that the institutional driving factors which led to large scale bribery in the telecom sector are being addressed. They identify five such areas where reforms should be implemented, before the Swiss government transfer the assets, namely (1) transparency of tendering process and corporate registry; (2) integrity of civil service abiding by law and not by personal loyalty; (3) fair trial and due process; (4) transparency of public finance; and (5) an independent anti-corruption agency. If implemented these reforms would have positive impact far beyond the telecom industry, as every sectors of the state and economy are affected by the same problem.

These reforms would be a significant step towards establishing the standards of good governance. They would give sufficient guarantees that huge scale bribery in Uzbekistan’s telecom sector would not be repeated, and that the returned assets would not be stolen all over again.

How to return one billion dollars stolen from the people of Uzbekistan